by Bill Murray

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Our executive branch is hobbled by an exhausted leader. Our legislative branch is unable to legislate and our Supreme Court has found sudden delight in partisanship.

This election was exhausting. We just got a lesson in how riven America is, culturally and politically. Until President Biden stood down, our political parties had both put up candidates unfit for the presidency. And yet one of those candidates is now set to govern.

After months of total immersion in the campaign, and in place of recriminations and hand wringing, this might be a good time to put down our partisanship and consider America’s place in the world.

As soon as we raise our heads from our screens it’s clear: the United States is promising the world more than it is prepared to deliver. It has no business claiming it can defend Europe against Russia and Taiwan against China at the same time. You know it, every international player knows it, and if America continues to claim that it’s so it will be called out soon enough.

So we need to make some changes. This was going to be true whichever party won the election, and if America gets the coming decade wrong, time-tested elements of the US-underwritten world operating system (US OS) will struggle to endure.

I argue not from ideology but from pragmatism, and maybe a bit of dated idealism. Here is Barack Obama:

“The United States of America has helped underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our citizens and the strength of our arms…. We have done so … because we seek a better future for our children and grandchildren, and we believe that their lives will be better if others’ children and grandchildren can live in freedom and prosperity.”

Obama’s six decades have extended to eighty years by now, and for all of America’s leadfoot missteps, its heavy-handedness and frequent lack of finesse, the world will miss the US OS when it’s gone.

The US Navy protects freedom of navigation for international cargo shipping, a $2.2 trillion global industry (transacted in dollars, naturally). Lose American protection of sea lanes and welcome mayhem back to the high seas.

America spends almost $9.5 billion a year on humanitarian aid and no one else comes close (The EU is a distant second at $2.1 billion). As the climate changes, more and more developing countries will clamor for American relief dollars.

There is no bigger international advocate for nuclear nonproliferation than the United States. Abandon this quest and say hello to an abomination of new nuclear rogues.

The United States, with the Five Eyes and others, mounts the world’s most extensive counterterrorism effort. Let this lapse and expect ever more rancid permutations of the likes of Aum Shinrikio, the Red Brigades, Shining Path and a rouge’s gallery of mujahideens.

At the turn of this century French Foreign Minister Hubert Vedrine coined a term for a transcendent United States; he called it a hyperpower. A quarter century later the once- hyperpower jostles for advantage among fast-rising near peers in all the world’s conflict zones.

The middle twenty-first century looks set to become an era of profound and accelerating technological advancement, with unknown potential to reshape social structures, disrupt the dynamics of economic systems and redefine power in unpredictable ways.

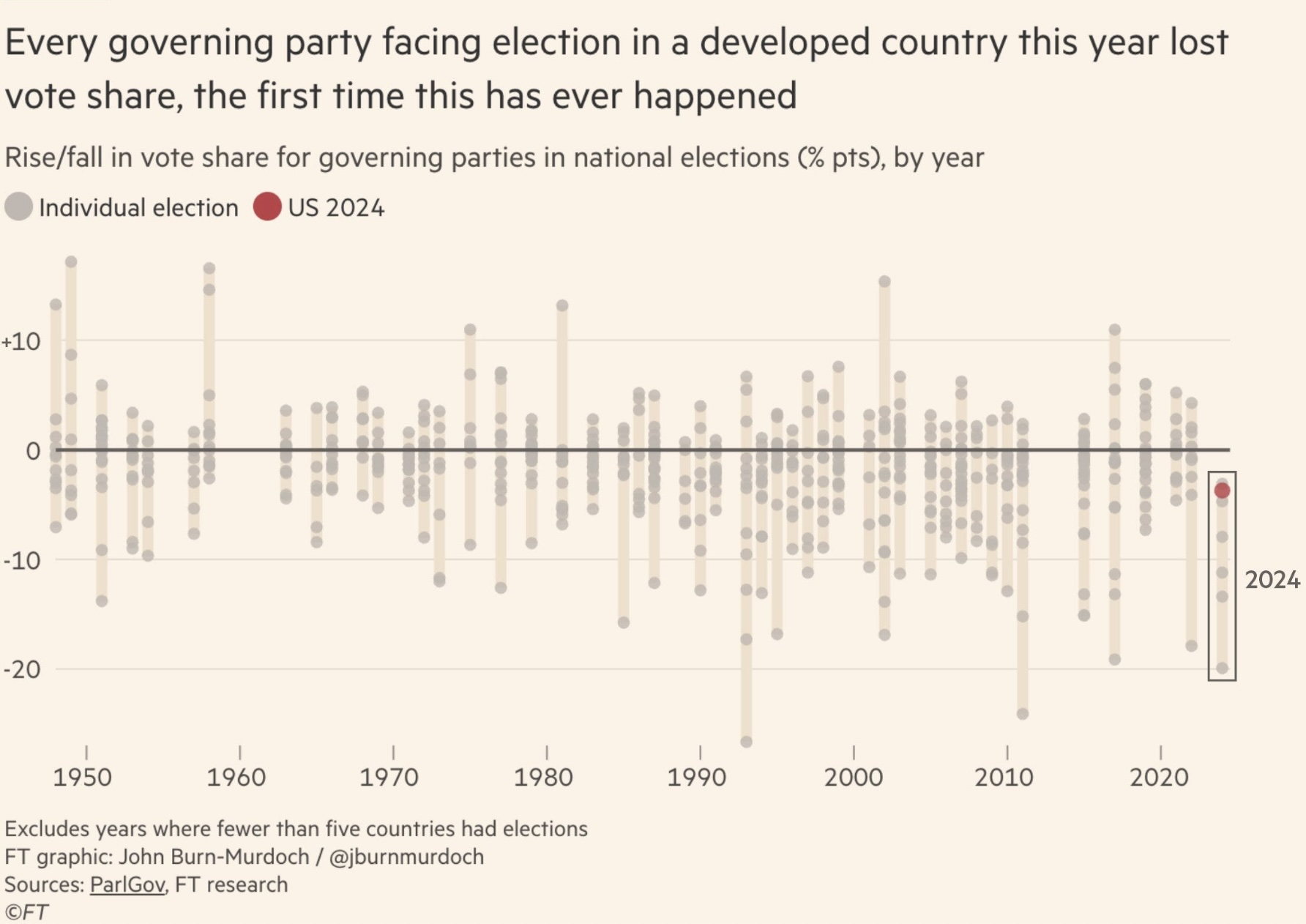

Movement toward disorder, in gradual but steady progress for years, now accelerates. Every governing party facing election in a developed country this year lost vote share, the first time this has ever happened.

Few post-WWII international institutions still effectively serve the broad international community. The authoritarian leaders of China, Russia, Iran and North Korea toil (apart and together) ever more closely to undermine the US OS. With the return of a more transactional, less-multilateral president they will likely make further progress.

Proliferating economic and political organizations jockey to become, if not fully anti-US alliances, at least alternatives. There are many: BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Belt and Road Initiative, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, among many more.

Even as there’s a sense that some of these groups make it up as they go along, it would be wrong to discount their long term chances. Amid a US retreat from world affairs, groups with members hostile to the ideas of freedom and democracy will surely refashion the parts of the world that they can, away from the broad US OS.

The most prominent of these new alliances, BRICS, met in the Russian Volga River city of Kazan last month. Just fifteen months ago Russian President Vladimir Putin stayed home from a BRICS summit in Johannesburg so South Africa needn’t enforce an International Criminal Court warrant for his arrest. Last month the leaders of Brazil, China, Indonesia and South Africa decided the ICC wasn’t such a barrier after all, and travelled to see their host.

The most prominent of these new alliances, BRICS, met in the Russian Volga River city of Kazan last month. Just fifteen months ago Russian President Vladimir Putin stayed home from a BRICS summit in Johannesburg so South Africa needn’t enforce an International Criminal Court warrant for his arrest. Last month the leaders of Brazil, China, Indonesia and South Africa decided the ICC wasn’t such a barrier after all, and travelled to see their host.

BRICS brought in Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates this year to become BRICS+. With these new members the BRICS+ grouping will vie to be the world’s most important source of future global growth, already accounting for some thirty-five percent of global GDP.

At last month’s summit Mr. Putin proposed a “BRICS Bridge,” a members’ mechanism to bypass the international SWIFT interbank payment settling mechanism. Whether BRICS+ could one day undermine the dollar’s reserve currency status is for a different column. But for the increasingly aligned ‘Axis of Authoritarians,’ BRICS+ looks to be a handy tool with which to bludgeon the US OS.

•••••

Post-WWII American leaders built out their framework for the world to suit the United States and its allies. Eighty years on, the confluence of accelerated technological change, new challenges to the US OS and the election of a disruptor American president feel poised to mark a fin de siècle in international politics.

In his history of the New Deal, William E. Leuchtenburg called the Great Depression one of the turning points in American history. “Even at the time,” he wrote, “men were aware of a dividing line.” Today men (and these days we include women) sense another dividing line. The next few years are a time of concentrated worldwide consequence.

America must decide how to again steer the future to its advantage, and it needs to get a move on. Since the US can not defend Europe against Russia and Taiwan against China at the same time, it shouldn’t assert that it will. And yet an explicit American declaration to defend the status quo in either Europe or the East China Sea would encourage mischief in the other theatre.

So the US must engage in steady, determined, close coordination with allies in both theaters, with one crucial and prominently trumpeted new element – a public, on the record declaration that America’s current security commitment is finite. In these waning years of US dominance, it is time to level with the allies: there is no room for you NOT to step up.

This will no doubt appeal to President-elect Trump’s sense of governance by showmanship, brinksmanship and dominance, but that is a coincidence. The need to reposition the United States would exist whether the next president were Joe Biden or Donald Trump. Such a new declaration of intent will create quite the reaction in both Europe and East Asia. And it must concentrate allies’ minds.

We’ll consider Europe for the rest of today’s column. Please subscribe to my Substack newsletter, Common Sense and Whiskey, where we will look at the dilemma of Ukraine next, and then survey US alliances in the East China Sea.

AMERICA AND EUROPE

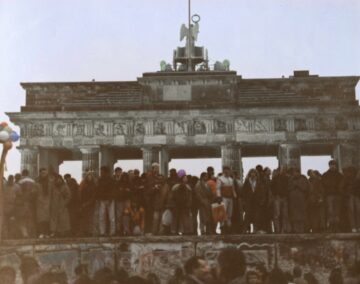

Whether the period between the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, and the election of Donald Trump exactly thirty-five years later comes to constitute an ‘era’ has yet to be seen, but it is possible. What began with exuberance in Berlin has come around today to a collective case of weak knees. Freedom needs a facelift. Liberalism labors under duress.

Whether the period between the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, and the election of Donald Trump exactly thirty-five years later comes to constitute an ‘era’ has yet to be seen, but it is possible. What began with exuberance in Berlin has come around today to a collective case of weak knees. Freedom needs a facelift. Liberalism labors under duress.

Barack Obama contended that “America’s commitment to global security will never waver. But in a world in which threats are more diffuse, and missions more complex, America cannot act alone. America alone cannot secure the peace.” Let’s use that as a starting point.

To borrow from an argument by the German Christian Democratic Union Member of Parliament Norbert Röttgen, it’s safe to say the outcome of Russia’s war on Ukraine will shape at least Europe’s middle-term destiny. Yet it looks as unlikely as ever that Europe’s Big Three, France, Germany and the UK, mean to step up.

“We cannot let the voters in Wisconsin decide on European security,” France’s Europe Minister Benjamin Haddad lamented to Politico,” as Europe goes about doing precisely that.

You could look at Donald Trump’s first term as a gift to Europe, offering governments an early warning and an opportunity to get serious about defense. They didn’t, and maybe they won’t until their own borders are threatened.

The day after President-elect Trump’s election German Chancellor Scholz fired his finance minister, the leader of the Free Democratic Party, Christian Lindner, who then collapsed the government.

“Scholz went on national TV,” an analyst wrote, “to declare that he wants to set aside money to support Ukraine, and for an increase in defence spending that has now become necessary after the victory of Trump.” Lindner would have none of that, since for him governance is all about the money, not the people who use it.

Few will miss Lindner, and since the FDP may drop below the five percent threshold for parliamentary representation, he may have led his not so merry band of extreme capitalists right out of parliament. So Scholz’s government falls before the publication of his predecessor’s memoir. Brutal.

Before calling France’s snap election last summer President Emmanuel Macron looked sufficiently pompous to puff clear up to the height of any domestic challenge. No longer. From that disaster forward, his far right opposition is just biding its time.

Eight years on, recovery from Brexit is still a full time job for the United Kingdom, with the economy deeply compromised by fourteen years of Tory rule, while the Labour Party appears to have chosen a charisma-free, non-visionary leader.

Admittedly, charging the Big Three with guaranteeing Europe’s security is a big ask. It would require doubling (probably more) each country’s defense spending and a focus on power projection avoided by Europeans for all eighty postwar years – except by former colonialists toward their colonies.

It would mean 155mm artillery shells rolling night and day off production lines across the continent. Defense contractors like Germany’s Rheinmetall, Nexter in France and BAE Systems in the UK maintain surplus capacity by design, so they can scale up production on short notice. The facilities of Norway’s Nammo, the major Nordic munitions producer, are designed with the capacity to increase shell production by 50% or more. The European Union should help individual governments via its European Defense Fund.

NATO doesn’t manage weapons production but it could facilitate a framework for smaller countries to combine their financial resources into common orders, similar to Czech President Petr Pavel’s collective artillery shell initiative last February.

(Progress has been made. Last summer Rheinmetall signed an €8.5 billion deal to replenish German 155mm stocks and supply Ukraine with the shells. In February, it broke ground on a new 155mm-focused factory in Lower Saxony. Europeans’ NATO spending was fifty percent higher in 2024 than before Russia invaded Crimea ten years before.)

It is past time to implement EU-wide defense procurement. At confirmation hearings, Kaja Kallas, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs-designate, characterized the EU as primarily an economic alliance. If it is, it’s her job to turn more of the EU economy toward foreign affairs.

As a former Estonian Prime Minister Ms. Kallas can speak with frontline authority to summon defense dollars from the larger EU toward the Polish/Baltic/Nordic nations, who viscerally and naturally lead opposition to Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Finally, Britain’s enduring quest for a special relationship with the United States could spur its Prime Minister to revive talks with France on integrating their nuclear forces into a credible European deterrent. The US should be delighted to help.

The US defense umbrella grants the European Union an unprecedented luxury: the freedom to sidestep hard questions of security and focus on quality of life. Which invites mocking (Boris Johnson and his bent bananas), and provides an entertaining pastime, kicking Brussels about as a meddlesome, out-of-touch bureaucracy.

The US defense umbrella grants the European Union an unprecedented luxury: the freedom to sidestep hard questions of security and focus on quality of life. Which invites mocking (Boris Johnson and his bent bananas), and provides an entertaining pastime, kicking Brussels about as a meddlesome, out-of-touch bureaucracy.

Donald Trump 47 could be the end of all that. His administration’s statecraft (if you quote this and insert a ‘sic’ after ‘statecraft’ I’ll understand) should center on exerting enough steady American pressure to deliver a Europe with its own defense capability without collapsing the whole project. The incoming administration may not do nuance, but getting the job done – by whatever means – grows steadily more urgent.

It may be that getting out in front of big, onrushing change is something Brussels just can not do. But even incremental steps can help shore up European security. The urgency now is to get moving.

Immigration is a marker of the times we live in, and climate change will keep it so. People want politicians to grapple with it. Entire political movements have risen against it. Brussels can co-opt a little of the rise of the xenophobic right with a tougher stance on its borders.

Italy has become mired in a plan to park migrants in Albania as quickly as the British Tories did with their Rwanda scheme. Back in the plausible world, Polish Prime Minister Tusk and the Finnish ruling National Coalition Party have viable policies. It’s no coincidence that each has a border with Russia and/or its satrapy Belarus, both of which follow policies of so-called “instrumentalized immigration.”

Finland has enacted, and Poland’s Civic Platform proposes, “emergency laws” to deal with their borders. The EU should endorse and legitimate such laws EU-wide for an interim period.

(Some of this runs contrary to my personal political orientation, but that orientation has just this month been repudiated by American voters, and we still have a problem to address. The world keeps turning and policy suggestions must at least be offered. So I have a few more.)

The EU could endorse more aggressive assimilation programs to both facilitate immigration and promote national defense. Systems of tiered benefits for new immigrants could be set up steer migrants toward labor in national security industries. Governments could promote an accelerated path to citizenship for immigrants working in, for example, munitions production or civil defense.

Joint research and development with the US in emerging military tech would improve efficiency and future interoperability in that realm. The incoming US administration could increase operational and training incentives for European countries that meet NATO’s defense spending target. Preferential access to joint exercises with the Americans might, in analyst language, drive compliance through positive reinforcement.

Finally, and only in eventual exasperation, the United States could solemnly announce its regret that in order to maintain its commitments elsewhere, it would be called upon to draw down its security commitments in Europe on a specific, gradual – but finite and loudly broadcast – timetable.

Barack Obama contended that “America’s commitment to global security will never waver. But in a world in which threats are more diffuse, and missions more complex, America cannot act alone. America alone cannot secure the peace.”

European allies should be incentivized, as loudly and publicly and relentlessly and as often as necessary, to step up and to publicly declare they are stakeholders in their own security. Because now, with an incoming Trump 47 administration, that is more than ever what they are.

•

I write more articles like this at Common Sense and Whiskey.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.