by Terese Svoboda

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

I was newly blonde when I flew out to LA to convince him to be the host of Voices & Visions, a PBS series on American poetry that I was producing. The dye job wasn’t planned. The proto-reality TV show Real People had put up a Free Haircut sign in Soho and like any poet, I was attracted to the Free. All I had to do for the series was transform from a mousy brown thirty-year-old to a hot blonde punk in a red jumpsuit. No problem. I did a bit of strutting around on the set, and the program was ready for reruns. Unbeknownst to me, the executive director had been working his Canadian connection, the daughter of media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who knew Donald Sutherland and his proclivity toward poetry. Lunch had already been scheduled.

Sutherland had the anthology of baseball poetry we’d sent to him on his desk, baseball being his only other passion outside of acting. Veteran of nearly a hundred movies by that time, he’d recently stunned audiences with his performance in Ordinary People. Did I dare to mention my brush with Real People? All I remember of the business part of that first hour was the way he quoted Auden while skating his long fingers over his desk – not as an arpeggio of show-offy emphasis but unconsciously following the cadence. I was impressed. He needn’t have auditioned – if that’s what it was – because we were barely paying scale. He called in his manager, they thought something could be done, and he suggested lunch. After arguing with his manager about what car to take, he appeared outside his office at the wheel of a beautiful white convertible. The manager held the door for me, I got in – and we drove across the street. Ah, Hollywood.

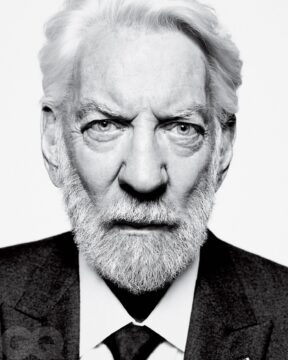

We must’ve eaten something. I must have talked about my time in Sudan, translating Nuer song, because he told me a story about a peace corps worker who was summarily hanged by Afghanis after she accidentally killed a child. I included the incident in my first novel Cannibal. I also must’ve told him about my brief stint as McGill’s rare manuscript curator because we visited a rare book dealer after lunch. He was a good listener. With that talent – rare in men – and those huge, expressive eyes and bourbon-honeyed voice, that hitch in his posture that remembered the polio he’d suffered as a child, and height – what other Hollywood actor is tall? – well, I was mesmerized. We stood in the stacks and slid out books and exclaimed over titles, but only he made a purchase. The dealer said he’d drop it off at his house. Actors do not carry parcels.

So what if actors can memorize? Poets memorize too. Nobel prize-winner Derek Walcott insisted his students recite long classic works from memory, as well as their own. The act of memorization draws the words tight to the mind because the struggle to bring them out causes a rich associative rush. But few poets can recite their poems well, memorized or not. With Sutherland it was as if he had just thought up an intricate rhyme scheme using a lot of assonance and linguistically interesting words with just enough narrative thrown in to break your heart. I’m sure he could do plummy but when he was just quoting something contemporary, it sounded like his own. We shook hands after our four-hour meeting, and he assured me we’d talk more.

We didn’t. The series was not hosted by Sutherland or anyone else. The executive director hadn’t expected me to succeed, and then he was faced with the deal. Did the Harvard critic Helen Vendler, one of our advisors, object? She so feared the audience would conflate the actor with the poet that she insisted I insert a scene in the pilot of him putting on Whitman’s wig. Sutherland’s presence in the series might have eclipsed the onscreen live poets, although Galway Kinnell, Derek Walcott, Robert Hass. Allen Ginsburg and Phil Levine put on quite a show themselves. Still, it was a terrible shame he wasn’t the host. His profound enthusiasm celebrated a case for poetry outside the world of letters, where the series most wanted to reach, and now he is dead and I am platinum for real.

I ran into Donald Sutherland one more time. In Victoria BC where I live half the year, we bought a boat from a man who’d worked as his double when Sutherland carried the torch for the Olympics in Vancouver. As gangly as the actor, Graham’s resemblance, particularly in the face, was quite remarkable: sharp blue eyes and white beard – and so was his recitation of Shakespeare. An English descendant of fishermen and those who brought their boats to Dunkirk, he had ranched for thirty years in Alberta before he settled beside the waters of Victoria. A wonderful man, said Graham. They went for a walk together.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.