by Martin Butler

We live in a rational age. Naturalism, the view that the fabric of the world can be – and should be – discovered and understood through the theories and methods of natural science, has dominated philosophy and contemporary thought for years. The theory of evolution and the big-bang theory of the origin of the universe are classic naturalistic explanations, and even those with a religious perspective for the most part concede the natural world to science. Oddly, those who pit their religious beliefs against accepted science, still often try to use scientific evidence to bolster their argument, inevitably resulting in bad science. Trying to ‘prove’ that the age of the earth accords with the biblical account is an example of this.

Many earlier philosophers produced non-naturalistic philosophies. Descartes’ dualism gave a central place to both natural and non-natural causes. The ghost in the machine account, while giving bodily functions a scientific explanation in terms of mechanical causes, understands mental capacities in terms of an immaterial, mental entity, something we might describe as spiritual. And even with the rise of the scientific world view, God could still be relied upon to fill in any gaps where science struggled – the so called ‘God of the gaps’. Newton, for example, despite his discovery of the laws of motion, believed that God intervened to ensure the proper movement of the planets within the solar system. Laplace, however, famously moved things towards full blooded naturalism when, in response to Napoleon’s question about the place of God in his philosophical system, he is supposed to have quipped that he had ‘no need for that hypothesis’. Here we have “a nature stripped of the divine” as Schiller put it. Or, according to the sociologist Max Weber, a disenchanted world

So where does this leave the spiritual, a term still widely used even by those who do not necessarily align themselves to any particular religious belief?

There are several options. One is to argue that although the term is widely used it doesn’t actually refer to anything real; the idea persists merely as a hang-over from a pre-scientific age when spiritual explanations were the only ones available. This approach does not need to claim that science explains everything, merely that it has a good record of explaining natural phenomena without recourse to spiritual causes, and so we can regard naturalism as a work in progress. Another option, perhaps a slightly more sophisticated version of the first, is to claim that it is fine to say that ‘spiritual’ phenomena exist as long as we understand that at bottom they can be understood naturalistically. Paranormal phenomena, for example, are often explained in terms of quantum mechanics. Certainly, in recent times script-writers have had a field-day exploring all kinds of purportedly paranormal phenomena with concepts taken from advanced physics.

But I want to argue that this is all beside the point, since what can legitimately be described as the spiritual actually plays a significant role in our everyday lives. It is not to be found on the edges of experience but is central to the human condition and yet cannot be reduced to naturalistic causes. Through its zealous desire to rid the world of irrational ‘superstition’, naturalism has thrown the baby out with the bath water, leaving us with a world view that seems to leave no room for some of the most important experiences we have. The spiritual is not weird because it is completely familiar. One of its distinguishing features is, I believe, that it does not play a role in the causal nexus of reality. In this it crucially differs from the approaches outlined above. In other words, we can accept the reality of the spiritual without looking for spiritual causes.

What do I mean by this? Take our encounters with other people. We don’t primarily see someone we meet as a set of amazingly complex bio-chemical and bio-mechanical processes. We see a person, a centre of self-conscious subjectivity, with hopes, fears, passions, responsibilities, and a particular story and perspective on the world that is unlike any other. We see ourselves, each a unique and infinite universe to itself. If we are limited to the concepts of objectively identifiable causes and effects in the way of naturalism, it’s hard to account for this. Roger Scruton makes this point particularly well with regard to the unique role the human face plays in our lives;

To say what it is we see when we see a face, a smile, a look, we must use concepts from another language than the language of science and make connections of a

nother kind from those that are the subject matter of causal laws. And what we witness, when we see the world in this way, is something far more important to us, and far more replete with meaning, than anything that could be captured by the biological sciences.[1]

Of course if we want to investigate how we are able to smile, to understand the configuration of muscles in the face that produces the smile, then we are back to the world of naturalism and physical causes. But Scruton goes on to say:

Through the example of the face we understand a little of what Oscar Wilde meant when he said that it is only a very shallow person who does not judge by appearances.

Of course Wilde is being mischievous with his turn of phrase but his point does cast some light on how I want to understand the spiritual. The Cartesian view would be that the significance of a smile derives from the inner spirit (or mind) which produces it – the ghost in the machine. The smile is merely an outward sign of the internal emotion, just as smoke is a sign of fire. It’s not the features of the face that count, what’s important is not in the smile but derives from what is behind the smile. But this is, I think, a deeply misleading picture. Of course there’s a sense in which a smile points us beyond itself, just as a beautiful picture points us to something beyond, but nevertheless the enchanted nature of a smile is still in the smile itself, the appearance and not what is behind it. It emerges from the physicality of the face, as a melody emerges from a particular set of physical vibrations in the air. The spiritual is immanent in the physical, they coexist in the same reality. In this sense we need to understand that we do and should judge by appearances, which in no way denies that we can be misled by a facial expression. A smile can deceive, but the meaning of the smile is not to be found in some other realm. Only because a facial expression can be enchanting can it be used to mislead so effectively.

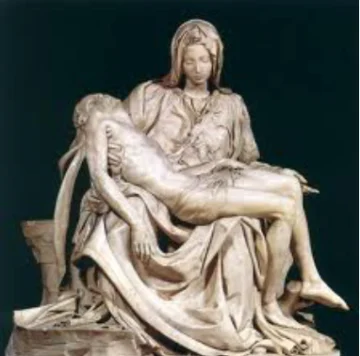

So an important truth about spirituality, as I conceive it, is that it exists in the world rather than occupying a Cartesian unseen shadow world that mysteriously interacts with the physical. The spiritual is a layer of meaning, often fleetingly perceived, that envelopes the human world. We become acutely aware of this dimension of reality when entranced by a piece of music, moved by a great work of art, overcome with love for someone, engrossed in a work of literature, moved by an awe-inspiring landscape or a beautiful building, or witnessing profoundly heroic or altruistic action. It is the spiritual that ultimately makes our lives worth living because we recognise it as intrinsically valuable – unlike the background physical reality from which it emerges. What I call ‘the spiritual’ Scruton calls ‘the lebenswelt’ which is a philosophical expression taken from German phenomenology. But it strikes me as odd that we need to draw on a somewhat obscure branch of philosophy when the reality we have in mind is so familiar. It can come, no doubt, through meditation or prayer, through work, companionship, in celebration, or in the face of tragedy or great adversity.

The question arises: why do we need the idea of the spiritual here at all? Is what I regard as the spiritual simply my emotional projection onto the inert material world? Hume was one of the early projectionists with his contention that “…the mind has a great propensity to spread itself on external objects.”[2] Charles Taylor’s concept of the ‘buffered self’ is similar[3]. Modernity, Taylor argues, is characterised by the idea that all meaning must derive from enclosed individual selves existing within an otherwise disenchanted world. Why can’t we explain the apparently enchanted nature of the world as simply our minds giving meaning to a disenchanted world?

But there’s something odd about this approach. First, there are instances where we do clearly project our feelings onto the world around us and they do not look anything like the examples I have given. Freudian psychology, for example, identifies the defence mechanism of projection: I do not want to admit that I have an irrational dislike for someone so project my own negative feelings onto her, making out it’s she who dislikes me. Unbiased outside observers could identify this as a clear example of projection, but it’s not the case with the examples I’ve given. Secondly, if I am deeply moved by, for example, a guitar solo but my friend is not, I might get him to listen to it more carefully to see if he can understand what I’m experiencing. According to the projectionist account I’m just trying to get him to project the same emotions as I am onto the sound vibrations. Far more sense to argue that he’s missing out on something valuable that exists in the music. Of course the landscape of aesthetics is large and complicated with many peaks, valleys and deceptions, but I cannot see how we make sense of it without some notion of the spiritual. Why would we want to banish spirituality from the world and yet embrace the idea that our minds somehow have the power to project these deeply meaningful experiences onto the world around us? The latter view seems far weirder than the former, and the mechanism whereby this projection takes place is completely obscure. The projectionist account ends up arguing that there is nothing special in the music itself, it’s just me kidding myself through some psychological trick which makes me believe there is something important in it. We have to tie ourselves in knots to try and explain away some of the most important and deeply meaningful experiences of our lives. We can accept that the spiritual evokes an emotional response in us but this is rather different from saying the emotional response is all there is.

This is only a challenge to a particularly restrictive version of naturalism. It does not deny that we must look to the theories and methods of natural science for causal explanation. What is challenged is the kind of scientism which claims that we can understand all human experience through the methods of natural science. We live intellectually in a post-revolutionary climate, the revolution being the scientific revolution. But as Charles Taylor points out, as with all post-revolutions there is a horror of backsliding.[4] The Puritans saw the return of ‘Popery’ in any kind of ritual, Marxists have a horror of anything that might be described as ‘bourgeois’. Similarly we have a horror of anything spiritual as a sign of a return to an unenlightened dark age, the age of woo-woo.

A basic question: does it really matter whether aspects of human experience we call spiritual are described as emotional projections or something else? Is it just a difference in language? It’s more, I think. If we are to be intellectually honest and have some adequate conception of the human condition I think we do need to use language that does justice to the richness of human experience. Theoretical descriptions do make a difference. We see that in politics. The view that most if not all human relationships can be reduced to relations of exchange can have a crippling effect on real human relations and denies something important. Naturalism is part of a tendency within modernity to provide uniform descriptions where everything is supposed to fit into a unidimensional model; the tendency, for example, towards instrumentalism where everything is seen as a potential resource[5]. We don’t even have to know exactly what we mean by ‘spiritual’ – but the word does have a secure enough place in the language for it to be clear that it is quite distinct from the emotional or the physical. The spiritual needs to be included in any adequate description of the world, for it is not weird at all.

***

[1] Scruton, R. 2014, The Soul of the World, Princeton press, Woodstock, p113

[2] Hume, D. 2000, A Treatise on Human Nature. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p112

[3] Taylor, C. 2007, A Secular Age, Belknap Press, London, p38

[4] Taylor, C. 2014, Iris Murdoch and Moral Philosophy, in: Dilemmas and Connections, Harvard University Press,

p19

[5] see Heidegger’s notion of enframing in his: Question Concerning technology.