by David Winner

Throughout most of my life, I periodically napped in the back sitting room of my parent’s house in Charlottesville, gazing at an enormous shelf of my father’s books.

Throughout most of my life, I periodically napped in the back sitting room of my parent’s house in Charlottesville, gazing at an enormous shelf of my father’s books.

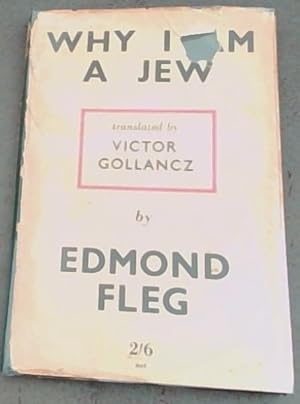

Why I am a Jew was an unlikely title to find. Though my father was most certainly a Jew, he was fiercely disconnected from all things Jewish. He claimed that he only learned that he was Jewish after he left his Jewish mother and Irish American stepfather behind in Pasadena to go to a very antisemitic Harvard in the late forties. He hated Woody Allen, Larry David, Bernie Sanders, and all other public Jews, never set foot in a synagogue or at a seder dinner, and was skeptical about the state of Israel.

Perhaps being brought up by such a non-Jewish Jew has influenced my perspective. When the news broke about the Hamas attacks in the fall, Angela, my wife, was cross with me before I even opened my mouth because she was stunned by what had happened and feared what I would say. I’ve had a long history of disparaging Israel.

A few days after the attacks, I came back to my house in Brooklyn to find Angela in conversation with our ultra-orthodox Jewish neighbors. They were in shock. Their seventeen-year-old son told us that Muslims had slated the following day for killing Jews around the world. Only Israel could protect us from the “animals.” The world, as he framed it, was overrun by an evil force out to get him and his community. Rather than confront his racism, I retreated inside. I didn’t think he would ever construct things any differently.

And my nearly opposite view would hardly matter if I somehow encountered Hamas. I wonder about the last thoughts of Vivian Silver, an elderly Israeli peace activist killed by Hamas. Did she feel betrayed, doubt her life’s work? Did she fear Israeli retribution, an apocalypse overtaking Gaza?

Of course, I’ve never met any members of Hamas, and, unlike my father at Harvard, I spent the first three decades of my life not hearing or experiencing anything remotely anti-Jewish. In my educated middle-class universe, antisemitism appeared to be an artifact from the past.

But that changed after I’d started teaching at a community college in Jersey City. A couple of decades ago in a class amorphously entitled Cultures and Values, I permitted a free-floating class conversation, stemming from my tiresome standard-issue liberalism. My students agreed that George W. Bush, the Iraq War, and Guantanamo were bad, but the real problem was the Jews. We were greedy and dishonest. We controlled the banks and the movies. The students in my class were a veritable United Nations of not liking the Jew: Irish, Italians, Poles, Nigerians, Filipinos, African Americans, American-born and Latin American-born Latinx, Indians, Pakistanis.

The sentiment did not come from the Palestinian situation as that did not seem to be on anybody’s radar. One contributing factor could have been the absence of Jews in Jersey City. Typical urban white flight occurred in the seventies, but some white people remained. The Jew flight, on the other hand, was more pronounced. There were so few Jews around to be juxtaposed against the negative tropes. And, often enough, my students worked in New York City for Jewish overlords, who were unkind and inconsiderate, as overlords tend to be.

When, on occasion, someone has identified my ethnicity and asked me about Jewish holidays that I’ve never heard of or Israel where I’ve never been, I’ve felt mildly affronted as false assumptions about me seem to have been made. Still, when anti-Jewish rhetoric streamed forth from my class, I owned my Jewishness. I spoke not about my gentile mother, my determined secularism, or my opposition to Israeli policies, and they were welcome to consider me rich and greedy if they so wished.

Just recently another class conversation bounced from the expensive condos going up all over Journal Square with deleterious rent hikes in their wake to the Jews who were supposedly the only ones building in the area. Annoyed, I demanded we “check the facts” and discuss it the following week. When I tried to do just that, determined to root out misinformation, I found webpage after webpage revealing the names and faces of neighborhood developers who, except for one black man with a notably non-Semitic name, were all Jews. I could no longer question the assumption on the part of my class, only challenge their unstated belief that the Jewish developers were acting intentionally in concert to screw them.

The question of antisemitism brings us back to Gaza. Recently, political argument seems to exist on an epistemological stage. We argue less about our own positions than what we believe others to believe. Take the conservative notion, for example, that there exists a huge wave of oppressively woke people invading classrooms and libraries. In terms of Gaza, there has been much discussion of how the American “left” has responded to the crisis. Does this left believe that the Israeli occupation of Gaza justifies the sadism of the Hamas attack?

Two opinion pieces in the New York Times that came out soon after October 7th _ Michelle Goldberg’s on October 12th and Jennifer Median and Lisa Lerer’s on October 20th _ contend that the left had indeed been celebrating the attack. But their examples of the left, the Connecticut and New York chapters of the Democratic Socialist of America, the Chicago and Los Angeles Black Lives Matters, a statement signed by many students at Harvard, didn’t seem particularly conclusive. MSNBC, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Mother Jones and other more mainstream progressive voices expressed horror about what happened.

When I brought up the events in Gaza and Israel with my Cultures and Values class in the fall, I hoped for a careful, controlled conversation in which I would avoid my errors in the past. Using the quasi-dictatorial power of a teacher in a classroom, I wanted to allow opinions about the state of Israel and Hamas while disallowing prejudiced comments about Jews or Arabs.

Most students sat this one out. The conversation was dominated by me and Eman, an Egyptian woman of about fifty who’d grown up in Kuwait until the Iraq invasion sent her back to Cairo from where she emigrated to the United States. Bravely speaking on this difficult topic, knowledgeable and remarkably articulate within the limitations of her English, Eman presented the Hamas attacks as purely anti-colonialist. Israel, in her view, had stolen Palestinian land in 1948 and has continued to expand. The two blue lines on the Israeli flag (a conspiracy theory first suggested by Yasser Arafat about twenty years ago) represented the Nile and the Euphrates, the huge swathe of territory Israel wished to take over.

When I suggested that both Hamas and Israel can be seen as terrorists, she avowed that the only reason why Hamas was viewed as a terrorist organization in the United States was because of the influence of our all-powerful Jewish population. Feeling stung, I argued that much of the support for Israel in America does not come from the relatively small and divided Jewish community but from fundamentalist Christians who tend towards an Israel-do-or-die attitude, viewing Palestine and Israel as the Judeo-Christian Holy Land.

“We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,” wrote MLK famously, “tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” Nabil, a sociology professor at my college wrote (in a book about Palestinian refugees in Jordan) that he’d only learned about the Holocaust quite late in life though, as an Israeli Arab, it had affected his entire narrative. Which is another example of the inherent messiness of this topic, the connections, the disconnects. Biden, sounding hesitant and confused as he sometimes can, suggested that the Palestinians in Gaza were exaggerating their casualties, a troubling assertion given the undiscovered bodies lying under rubble and the growing body count. Meanwhile, he was attacked by Republicans and scorned by more conservative Jews for even suggesting that Israel try to minimize civilian casualties.

In the many months since the Hamas attack, Israel has remorselessly killed tens of thousands, targeting hospitals and refugee camps. Rather than provide aid to Gaza, they have prevented humanitarian groups from doing so, killing nearly a thousand international aid workers. Twice, their apparent targeting of civilians has forced even Netanyahu to apologize. An antisemite following these stories might not reach for the relatively mild stereotypes of greedy, media-controlling Jews but darker older ones, the drinking of Christian blood, and the “murder” of Christ himself.

A massive campus protest movement began in the winter and spring of 2024, the details of which (the taking over an administration building at Columbia for the first time in decades) are familiar to readers. Netanyahu has labeled these protestors antisemitic mobs though surely most protestors, many of whom are Jews, are spurred by humanitarian concerns.

Criticism of Israel can be falsely classified as antisemitic whereas antisemites can use the plight of Palestinians to bolster their prejudice. Genuine righteous anger with Israel over Gaza only turns antisemitic when those who express it already have an antipathy to Jews. Apparently, Laos, where Jews are absent, is the least antisemitic country in the world except, I posit, for Israel itself. Rather than protect us from antisemitism, its inflammatory policies and rhetoric spur it on.

When considering Israel and Gaza, we must hope that misinformation, tribal allegiance, and anger don’t cloud our attempts to understand it. We must hope that Israel ceases fire at long last and that those chanting “Free Palestine” and “From the River to the Sea” wish only for human rights rather than another Holocaust of the Jews.

I’ll try to answer the question asked by the book on my father’s shelf, which has long been removed as he has died, and his house has been sold. I am a Jew in several ways, which, in the best Jewish tradition, may contradict each other.

Like paranoid Woody Allen in Annie Hall turning “you” into “Jew” in his mind, I imagine a look of glee on the faces of Facebook friends who only post politically about Israel as if there are no other issues in the world. Rather than caring about Palestinians or democracy, I suspect them of relishing an opportunity to take it to the Jews.

In the fall, a school in Scarsdale, New York canceled their annual Halloween UNICEF fundraiser, calling the institution antisemitic because, among other things, they referred to the “Palestinian state” when one does not exist. Using one of the world’s great iniquities as an excuse to cancel UNICEF made me angry like Jerry Seinfeld growling like a dog, the name, “Newman,” steaming from his lips, or Rodney Dangerfield’s head, a decade or so further back, bulging from his neck as he gets “no respect.”

I hope I have not hurt or offended anyone. Israeli violence is ongoing. And it is not antisemitic or unfeeling towards Jews who suffered on October 7th to demand that it stop, that an equitable two-state solution be sought, one which gives both Palestinians and Israelis free and peaceful passage from the river to the sea.

A recent visit to Hiroshima brought my mind to Gaza, an imperfect analogy but a hopeful aspiration.

America decimated Hiroshima as Israel has decimated Gaza. The Hiroshima Dome, a building whose bones survived the destruction, has become a symbol of peace. I looked upon it and wished the same for the Omari Mosque in Gaza, lying partially destroyed by Israeli and perhaps American bombs.

(With apologies to Edmund Fleg, whose book on my father’s shelf has nothing to do with any of this.)