by Leanne Ogasawara

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

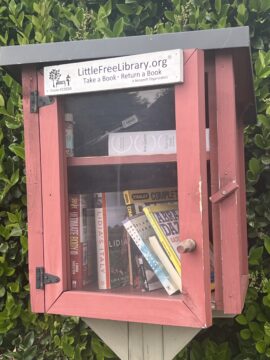

An avid walker, I like making great rambling loops around my neighborhood. Along the way, I’ve noticed four Little Free Libraries that I must have probably strolled past, oblivious, a thousand times… each is cute in its own way; one built surrounded by bird feeders, another positioned at the perfect height for a small child to reach inside. My favorite is in a neighborhood where the houses are a million dollars more expensive than the one’s on my side of the street—in California, it’s all about the zip code.

Having spent the past ten years building a massive multi-room library of my own, I felt I should leave these little libraries to others—But then I thought, why not just have a quick peak inside? And maybe even distribute a few books of my own…. And so, I trotted over to the one closest to my house.

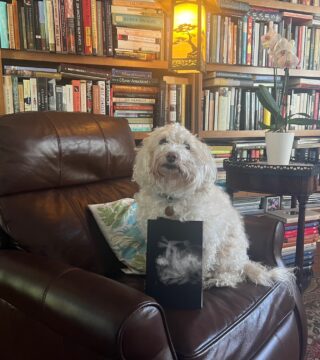

Being one of those kinds of people who cares about what book sits next to another on the shelf, I spend a lot of time arranging my library. I like it when books of a kind sit side-by-side with others of a like mind. I think of them in conversation with each other: there are stacks of fiction and nonfiction related to Japan across the room from rows of essays and stories roughly revolving around the art of translation. In pride of place is my shelf of “top ten novels” and shelves devoted to the work of mentors and teachers. And, I have multiple shelves of books with ghosts. These are not ghost stories per se, but are works of speculative fiction that embrace the magical real in the world.

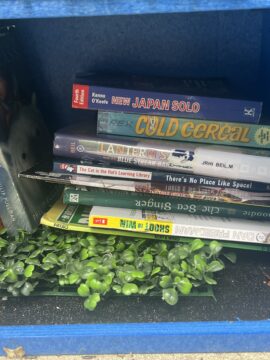

My shelves are perfectly organized—even if I am the only person in the world that understands the system. So, I was slightly unnerved by the Little Library’s jumble of books across the street: Michell Zuckoff’s WWII story, Lost in Shangri-La, placed upside-down on Jonathan Kellerman’s murder mystery The Ghost Orchid —but looking more carefully I did discern that “books about books” dominated the little jumble. There was Shauna Robinson’s Must Love Books, Janet Charles’ The Paris Library, and The Lost Book Party by Karen Dukess… in the corner, John Updike sat above Isaac Bashevis Singer….

My shelves are perfectly organized—even if I am the only person in the world that understands the system. So, I was slightly unnerved by the Little Library’s jumble of books across the street: Michell Zuckoff’s WWII story, Lost in Shangri-La, placed upside-down on Jonathan Kellerman’s murder mystery The Ghost Orchid —but looking more carefully I did discern that “books about books” dominated the little jumble. There was Shauna Robinson’s Must Love Books, Janet Charles’ The Paris Library, and The Lost Book Party by Karen Dukess… in the corner, John Updike sat above Isaac Bashevis Singer….

Honestly, I could have been tempted by any of them…. but there was one mysterious book that caught my attention above the rest:

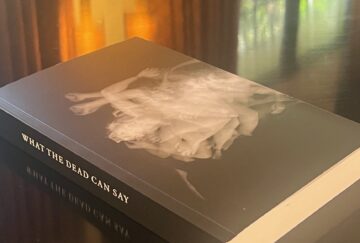

What the Dead Can Say

It had a glamorous black and white cover. The background was a rich, shining black like the lacquer on a Steinway piano. And there, as if swimming in the velvety dark sea, was a pale white image of people tangled up in each other’s arms. It shimmered. A quick Google search proved it to be a long-exposure photograph of a couple sleeping in bed over the course of one night, by Austrian photographer Paul Maria Schneggenburger. The photographer has taken a series of these “sleep of the beloved” photographs which evoke a wonderful supernatural quality…. What happens to us when we sleep anyway?

And I think we can all agree that you really can tell a book by its cover, right?

2.

2.

But wait… this baby had no author.

There are no blurbs or jacket copy—seeking to persuade. And no information about the author no matter where I looked (except for the words: “Author Unseen”).

Just a few poems pave the way:

No one knows what happens at the end of the journey. No one knows where the soul goes. —Jeanette Winterson

For the soul is a wanderer with many hands and feet —Joy Harjo

I gave birth to my infinite being, but I had to wrench myself out of me with forceps. –Fernando Pessoa

Even before I began reading, I was already imagining how attractive this book would look sitting on my shelf of ghosts.

Salman Rushdie one said: ‘Now I know what a ghost is. Unfinished business, that’s what.’

It’s true. Whether in the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Isabel Allende, or in Yangsze Choo’s The Ghost Bride ….or in linked story collections like the Hawaiian inspired ghost stories in Every Drop Is a Man’s Nightmare by Megan Kamalei Kakimoto and Aoko Matsuda’s 2020 linked story collection Where the Wild Ladies Are, (translated by Polly Barton)… or my all-time favorite: The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories by Jamil Jan Kochai. In all these stories, the ghosts are some kind of unfinished business.

But in What the Dead Can Say, the ghosts are not just unfinished business; for they are the storytellers too. They

swoop and circle over the town like birds and never come down – the perfect, soaring denial of death.

Others

stand at street corners and shout out convoluted philosophical musings, every last word directed to a living audience that walks by and hears not a thing. Others let the wind cast them about, as if they were scraps of paper, discarded napkins streaked with mustard, a torn corner of a newspaper – whatever circles and tumbled down any alley or broad avenue.

Many cling to their families. Confused over the sudden severing, a three-year old child follows her parents even after death, searching, questioning… often there is a memory they cannot bear to face, something they said or did that caused them to feel deep shame while they were alive, and it is this memory that continues to haunt them after death.

I am reminded of David Eagleman’s wonderful book, In Sum: Forty Tales of the Afterlives, in which the author describes many possible scenarios of the afterlife. One in particular has haunted me for over a decade. In it, a person is made to dwell for eternity in their favorite memory.

This is so Proustian, don’t you think?

Proust, of course, saw that how we occupy actual time is what gives meaning to our lives vis-a-vis our memories. And so in this world where time, meaning and vision come together, Proust was vehemently opposed to idleness, philistinism and amusement, or anything leading to numbness and “killing time.”

In Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, the story begins in the describing of the narrator’s happiest moment– the moment he and his beloved first made love in the hero’s Merhamet Apartment. It was– the narrator says– the most perfect and joyous moment of his life. David Eagleman, however, in an interview he did on BBC Radio suggested that most people would not choose a love affair as their one eternal moment; for most people would prefer to dwell in something less intense and more pleasantly banal, he said–like sitting on a bench with their best friend in a garden.

I know what moment I would choose, do you?

But what if instead of your favorite memory, your eternity was a painful moment in your life that was more like a shameful haunting… or of some unfinished business? Wouldn’t that be awful? To live in an experience of shame for an eternity?

3.

3.

In Japan, people honor the dead for forty-nine years after they die. Not everyone does this, but the way the dead are remembered and honored had a deep impact on me since I arrived there so shortly after my own father’s death.

My first husband Tetsuya was always smiling and laughing—except when it came to the dead. Whenever he talked about my father, he’d grow solemn and suddenly appear much older than his age. He was surprised that I would leave home soon after my father’s death.

In Japan, he said, people take funerals and mourning very seriously.

Later, he set up a small altar in my apartment and suggested I offer rice and flowers to my dad every day, praying for his eternal rest in paradise. “Just talk to him,” Tetsuya said.

He plopped onto his knees in front of the altar, making it clear with his outstretched hand that I should kneel at his side. I watched as he lit a stick of incense and placed it in front of a framed photograph of my dad. Putting his hands together, he prayed.

“What are you saying?” I felt awkward sitting in front of the photo.

He looked surprised. “I am calling upon Amida Buddha. But you don’t have to do that. Just communicate from your heart. I think he is listening.”

And this was how I began to sit in front of a picture of my father. With sweet incense smoldering, I’d tell him about Tokyo. About the beautiful seasons. About Tetsuya.

The dead leave a hole in our hearts that we long to fill. At the same time, I think we hope that they will rest in peace. Part of the traditions and offerings in Japan are designed to help the dead make peace with their new reality, to remember them, but to try and encourage them not to keep clinging to our world. But that said, the Japanese (along with several other cultures that come to mind from West Africa to Borneo) believe in death that comes in two phases. At first, it is believed, the dead do cling to their lives, their families, the world. And so in some cultures there is some time between the first ceremony when the dead are believed to be close at hand to a second, when they are bid off to the other world.

In some Dayak cultures in Borneo, the dead are first placed in great jars before finally being buried later; while in Sulawesi, they are placed in shallow graves near the home until money can be saved for a gigantic sendoff in elaborate week-long funerals.

Death is the biggest event of life and is honored as such.

4.

4.

When I was in my mid-forties, I walked away from everything. Leaving all my stuff behind was a lot easier than you might imagine. I had my son, after all. And wasn’t that all that mattered? In truth, I didn’t miss my things that much.

Except for my books. Those haunted my thoughts and I longed for them endlessly. So, a few years ago, I started recreating my old library.

Beginning with building bookcases, I tried to remember the titles. Like lost memories. Like lost stories. The more titles I remembered, the more books I bought—until all the shelves were lined with them, and there were teetering towers of books everywhere, rising up toward the ceilings in every room.

Rebuilding my life, brick by brick and book by book, sometimes felt like I was constructing a lifeboat, not a library.

In Vienna, the Holocaust Memorial in the Judenplatz, is known as the “Nameless Library.” The monument depicts each lost life as a book. Facing inward, their titles unrevealed. Nothing but empty spaces, where once there were stories. All those memories and lives eradicated, as if an entire people had been drowned in the ocean. An important library lost.

If our lives are books, where would you want to sit on the shelf?

Would you want to be a commercial best seller or would you want your life to be a beautiful but nameless story? As a translator, I am used to being invisible. And so the author-less book is incredibly attractive to me: a provocation against the world that turns everything into a resource. A brand. Even our own lives.

As philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes in his latest book, The Crisis of Narration, we have gone from storytelling animals to story-selling ones…..

In The Millions, I have written about my negative experiences in fiction workshops and about American publishing. After twenty years in Japan, where I thought, dreamt, and read mainly in Japanese, my thinking and writing naturally reflects Japanese storytelling styles. I prefer more meditative writing with constant pivots and turns. I love surprises, and prefer the lyric over the concrete, the “nobility of failure” over the hero’s journey. And more than anything, I love books that refer to other books.

But publishing has become —like so many aspects of our lives— about products.

It is not only artists that are being branded but the writing itself is being “managed”—many times with TV in mind. There is a certain style that is strongly promoted in workshops of short, almost journalistic sentences, snappy paragraphs, simple verb tenses, and no adverbs—not ever! Writers are taught to discard a lot of the language we speak and think in. Why is that?

What would you say about someone who says no to this? An authorless author? And a story teller who is not a story-seller?

5.

5.

There is a gilded plaque above the great wooden doors to the famous Abbey Library of St. Gall, in Switzerland. Written in Greek, the letters read: “house of healing for the soul.” People thought it was the perfect motto for the perfect library, which was built in 1760. But many did not realize that the saying was far older than the Baroque library at St Gall; for this claim that books are medicine for the heart dates back some 3,000 years to the great library of Pharaoh Ramses II. Famous among the ancient pharaohs for his military prowess and the glorious splendor of his court, he is known to bibliophiles for his vast library of sacred books.

6.

In the back of my copy of What the Dead Can Say, there is a handwritten number, 575/1000.

I realized seeing this that the artist has a vision— and like a numbered print— puts the work out into the world. Hand-delivered?

Trying to discover more about this project, I found a Reddit post that beautifully echoes my own experience of stumbling on something magical in the form of this mysterious book and finding oneself swept up in the mystery of a story. The Reddit poster got his hands on number 905/1000—from a little free library in Oregon. How lucky he was—and how lucky I am.

I now have the Little Free Library app on my phone—and I will be making a point to search them out wherever I travel. The little moments of quirky serendipity that they offer are a reminder about what art and life are really about—the haunting, connecting, sharing, and enchantment of the stories that make up our lives.

We are ourselves small libraries.

7.

7.

For me, the mystery continued.

Hidden in the back of What the Dead Can Say was a tiny bar code. Without thinking, I trained my camera on it and was whisked away to an Instagram account where one of the ghosts of the story continues her interrogation of memories— discovering the joy of little free libraries herself!

The expanding, revolving network of the free little libraries … a mishmash of juxtapositions, the best of these becoming so much more than the sum of their parts.