by Rebecca Baumgartner

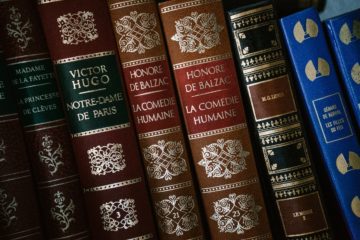

I’m currently reading The Hunchback of Notre-Dame in translation, and it’s got me thinking about how much we rely on translators to bring us literature from around the world, and how important it is to be able to trust what they tell us. I can only imagine the patience and creativity, the erudition and intuition, required to be a good translator. I’m deeply beholden to every translator who has enriched my life by unlocking the magic of Anna Karenina, Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, War and Peace, A Young Doctor’s Notebook, the novels of Carlos Ruiz Zafón, the novels of Anna Gavalda, The Three Musketeers, Beowulf, the haiku of Issa and Basho, all the stories of Greek mythology, and now – The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

The duty of a translator assumes outsize importance once you get invested in a story. It’s crucial they get it right; you have to be able to trust their interpretation and sense of style. You want them to be faithful to the spirit and letter of the original, but if you had to prioritize one over the other, you want the spirit to come first. Most of all you want the impossible: To borrow their French- or Italian-speaking brain for a few hundred pages, to see into the soul of Victor Hugo or Leo Tolstoy, however briefly, with as little mediation as possible, to be able to believe that this text was written in English all along, that you are drinking from the original source. When done well, this is a gift that can never be adequately appreciated or repaid.

The flip side of this weighty responsibility is an equally weighty disappointment if it’s handled poorly. Even in the best translations, I’ve stumbled on phrasings that are simply too clunky or awkward to be the best possible rendering, and it grates like a pebble in my shoe. I’ve read novels translated from Russian that persist in translating “bored” as “dull” – words that might seem interchangeable, until you read a sentence saying that someone is dull, when it’s obvious from context that what they really mean is that they’re bored. I’ve seen the word “explanation” used to describe what should have been translated as “argument” (characters having violent explanations in the next room, for example).

One of the most cringe-inducing examples of a mistranslation came to my attention recently when a character referenced the Latin motto “Sapere aude,” which was the Enlightenment-era rallying cry meaning “Dare to be wise” or “Dare to know.” Unfortunately, the translator rendered this as “To learn, listen,” mistakenly confusing the verbs audere (to dare) and audire (to listen). I only knew this was a mistake because of my rusty Latin. But other readers have no choice but to take that mistranslation at face value.

It’s true that at the level of the book’s overall plot, knowing what this phrase means isn’t terribly important – but for this specific character in this specific scene, it is important. The man in question is a Faustian character driven to heights of scientific overreach that ultimately divorces him from his own humanity. In that context, “To learn, listen” is exactly the opposite of what this character would believe. He is self-driven to a fault, listening to no one, least of all his own conscience. “Dare to know” is the more apt summary of his belief system, a single-minded grasping after knowledge that leads to his corruption.

I want to make it clear that I’m not trying to be pedantic for the fun of it, nor do I have some special attachment to Latin being used correctly. My concern is that this one mistake is perhaps the only one I caught out of many, only because I knew enough Latin to know better. But what about the phrases in Greek that the same translator rendered into English? Were they right? I have no idea. After that mistake, my trust in the translator was shaken, and I found myself looking up other words and phrases out of doubt. I suspected a few other Latin phrases were partially wrong, but I wanted to enjoy the book, not build a case against the translator. Unfortunately this became too time-consuming and I had to resign myself to accepting what was presented to me.

Coincidentally, around the time of the “Sapere aude” scandal, I happened to see a doctor who I strongly suspected of being a quack – or if not outright unqualified, then at the very least inattentive, overwhelmed, and scatterbrained, which can often amount to the same thing as far as the patient is concerned. I had walked into his office in pain, wanting answers, expecting rigor and experience. Above all, without even consciously being aware of it, I walked into the building full of trust for this person I had never met, purely because of the institution and knowledge he represented.

When I left his office after an unsettlingly unprofessional exam, what bothered me most was not that I was still in pain, but that I felt this person I had trusted had not listened to me, had misunderstood what my body was communicating, and wasn’t competent or organized enough to do anything about it. For a patient, losing trust in someone’s ability to help you can be scarier than facing pain.

As I thought about this event afterwards, it struck me that I was feeling almost the same as when I discovered the Latin mistranslation in my book. Obviously the stakes are very different – not even the most committed classicist can sue a translator for malpractice if their enjoyment of a book is compromised by shoddy Latin – but the underlying cause and emotional kickback is remarkably similar. I felt betrayed (if that’s not too melodramatic). I felt that I was on the bad end of a dereliction of duty. In both cases, I wanted to shout, “Someone should have been more careful and paid more attention!” It doesn’t require monumental feats of wisdom to know the difference between audere and audire, or to listen carefully to a patient. It’s mostly a matter of caring enough to pay attention.

This reminded me of a bit I heard David Brooks mention in an interview about his book How to Know a Person, about paying attention being a moral act. We all have a moral duty to pay attention to our fellow humans, what they need, who they are, and how our behaviors affect them. For doctors, this moral imperative is obviously on the stronger end of the spectrum, but the various responsibilities we all have fall somewhere on this spectrum.

In his book The World Beyond Your Head, Matthew B. Crawford says that “there is a moral imperative to pay attention to the shared world, and not get locked up in your own head.” He goes on to describe Iris Murdoch’s idea that to be good, a person must “know certain things about his surroundings, most obviously the existence of other people and their claims.” Crawford gives the example of drivers distracted by cell phone conversations to make the point that such “inattentional blindness,” when coupled with a tool as deadly as a car, “becomes an apt topic in discussions of what we owe one another” and that “in the attentional commons, circumspection – literally looking around – would be one element of justice.”

A bad doctor and an uncircumspect translator are both bad in proportion to the good that they would be able to perform if they were performing at their profession’s fullest potential. When someone has such specialized knowledge (which is, in some cases, literally Greek to us), their poor choices affect what version of reality we get to experience. We face a cascade of questions: Was this an isolated mistake, or is this person fundamentally untrustworthy? Are they a reliable guide through the realms of French literature or the musculoskeletal system, both of which are equally incomprehensible to me? What else have they been wrong about? How can I protect myself from their mistakes?

The convenience of tools like Google Translate and online sources like WebMD would seem to take some of the moral load off of these professionals. There’s certainly a degree to which this democratization of knowledge is empowering for those without such specialized knowledge. We have more ways of getting second opinions, more systems of accountability, and more opportunities to fact-check. I use “Dr. Google” all the time, if not to diagnose myself with terrible diseases late at night, then to compare medications, see how serious a symptom is, or learn more about a loved one’s illness.

But there’s a reason why no one wants to read an entire novel that’s been run through Google Translate and why no one wants to embark on important decisions about their health based only on WebMD’s advice. We have information in spades; what we need are interpreters. What we’re really looking for is a satisfying narrative that makes sense, a thread that connects seemingly disparate details to produce a unified tapestry. A novel, a diagnosis, a translated phrase, a connection between two symptoms: These are the strands that we need a professional to weave together for us. They create coherence. And they can only do so when their attention has been trained to focus on the right things, and when the systems they’re part of are built in ways that let them sustain that attention and act thoughtfully.

This complicates the story that many of us told ourselves and others during the height of the pandemic, and in various other political contexts too: “Trust the experts.” Deciding who to listen to when there’s uncertainty is fraught. Unless we’re virologists or climate scientists or orthopedists or bilingual in French, we have to defer to someone else to do those things in our lives. No one can know everything they need to know in order to survive and thrive.

But trusting experts isn’t quite the right advice; instead, we should trust systems of expertise. We should invest our epistemic trust in systems that have methodical ways of admitting error and continuously improving built into their design, like the scientific method. It’s the best way we have for making sure our ideas are getting more correct over time. Unlike the admonition to “Trust the experts,” this doesn’t require you to trust any individual scientist, but rather the system that they try to live up to. As Jamie Watson, a bioethicist, writes in The Philosophers’ Magazine, “There are lots of reasons to be sceptical about experts. But it’s important to note that those reasons have nothing to do with expertise.”

For the most part, these systems of error-correction happen at a much larger scale than any single person can affect (which is for the best, given how fallible each individual person is). But even regular folks like me can train themselves to spot mistakes in areas outside their expertise. You can do this by knowing how to interpret research results with healthy skepticism and by understanding the various incentives at play when you’re deciding how much to trust an expert. Above all, remind yourself that no expert is infallible and take it upon yourself to ask questions and find out as much as you can: Sapere aude.