by Carol A Westbrook

Dementia refers to progressive, irreversible cognitive impairment usually seen in the elderly. The clinical findings of dementia almost always include some degree of memory impairment. We didn’t know much about how memories were formed in the brain until 1953, when the now-famous patient named Henry Molaison, HM, had removal of an area in the temporal lobe of his brain called the “hippocampus” the operations successfully prevented seizures, but unfortunately HM also lost the ability to form new memories of events, and his recollection of anything that happened in the preceding eleven years was severely impaired. Other types of memories such as learning physical skills were not affected. This was the first step in learning about how and where memories are formed in the human brain.

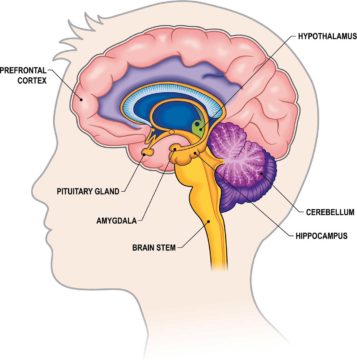

We now know that the hippocampus plays an important part in the formation of new memories by the physical interaction and modification of neurons, and it also processes short -term memories into long-term memories, which are then stored in the frontal cortex. Specific brain structures have other specific tasks in memory development, (see figure 2) such as the amygdala, the area of the brain which adds emotional pertinence to memories such as fear, pleasure or pain, whereas physical skills and movement are dependent on the cerebellum. We are beginning to understand how and why specific brain lesions can lead to different forms of dementia.

Many people experience memory problems as they age. This is often regarded as a normal part of growing old, one more annoyance to put up with, like bad knees or wrinkles. We find ways to work around our memory problems; we may use memory aids like checklists, or carry a schedule on our cell phone, or rely on cellphone alarms to make important appointments. Calendars and watches remind us of the date; databases list our friends’ contact information, and interactive maps help remind us how to get there. AD patients use these same methods. But when memory loss continues to worsen, or if it interferes with normal life, we diagnose dementia.

Calendars and watches remind us of the date; databases list our friends’ contact information, and interactive maps help remind us how to get there. AD patients use these same methods. But when memory loss continues to worsen, or if it interferes with normal life, we diagnose dementia.

On the other hand, when memory loss or other thinking problems appear to be greater than expected for the patient’s age and education, but not as severe as those seen in full-blown AD, we diagnose Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Screening tools can help detect and quantitate MCI, monitoring it over months and years, especially if there are concerns about the possibility of dementia developing, or if there are questions about treatment or nursing home placement. An example of part of a screening process is called the “the Three-Word Test.” For this test, a patient will be asked to remember three words at the beginning of an exam, and then several minutes later will be asked to recall them. The patient is scored on the basis of the number of words he can recollect.

Many families living with a person who has MCI may be unaware because they have been become adept at covering for him, often without realizing they are doing so. For example, the family members may finish sentences for the patient, or supply words he has forgotten. Difficult tasks will be performed for him in the interests of “giving Grandpa a hand.” He is offered a lift so he doesn’t have to drive. And so on. It is only when the person is removed from familiar settings, such as when he is hospitalized, that his limitations become apparent.

Difficult tasks will be performed for him in the interests of “giving Grandpa a hand.” He is offered a lift so he doesn’t have to drive. And so on. It is only when the person is removed from familiar settings, such as when he is hospitalized, that his limitations become apparent.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

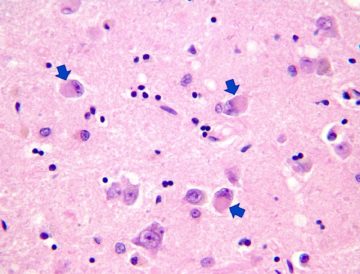

There are many forms of dementia, the most common of which is Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). More than 6 million Americans have AD, and as a result, it is the most frequently studied, and we know the most about it. AD results from the deposition of apparently normal amyloid proteins on the neuron cell, producing abnormal plaques on the cell surface. Precipitates of abnormal tau protein, which look like tangles under the microscope, also occur. These plaques and tangles preferentially accumulate in neurons of the hippocampus, interfering with the formation of new memories. Neurons stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. As damage becomes more widespread, it spreads to other areas in the cerebral cortex responsible for language, reasoning and social behavior. A patient will behave inappropriately, forget words, and have difficulty recognizing friends. Eventually he loses the ability to live independently, and to care for himself; death ensues. The rate of progression varies greatly among AD patients. A small number of AD cases are caused by a gene mutation, and these occur earlier in life than usual AD, but most are sporadic..

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB)

The next most common form of dementia is called Dementia with Lewy Body, DLB. DLB was only recognized as a distinct form of dementia in 1976, and many people have never heard of it. It takes its name from the clumps tau proteins, which can be seen under the microscopeThese precipitates are called “Lewy Bodies,” and can be seen in other types of dementia, though not as abundantly. LBD is characterized by changes in sleep, behavior, cognition, movement, and the autonomic nervous system. A sleep behavior disorder in which people act out their dreams, is a core feature. It is due to the loss of muscle paralysis that normally occurs during REM sleep. Also prominent are visual hallucinations, and movement disorders similar to the slowness seen in Parkinson’s disease. Memory loss is not prominent.

DLB is one of two Lewy Body dementias, the other being dementia when it occurs in Parkinson’s disease. It has been estimated that 50 – 80% of people with Parkinson’s disease develop a dementia, and the form is always of a Lewy Body disease.

DLB can be hereditary, in which case mutations are seen in the normal tau proteins, but most are sporadic. There is no cure, but symptoms can sometimes be managed with medication

Frontotemporal Dementia

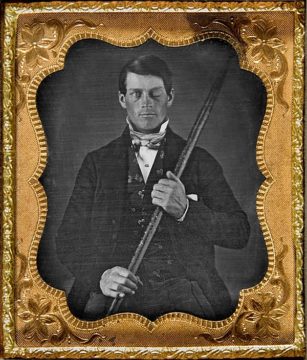

Frontotemporal dementia represents another case in which a rare brain accident led to better understanding of brain function. In this instance, it was the case of Phineas Cage, a railroad engineer who, in1848, survived a freak accident in which an iron rod was driven completely through his head, destroying almost the entire left frontal lobe. He remained conscious, but the accident changed his personality, so that his friends swore they didn’t know him anymore.

The accident changed his personality. His intellect went down, and he swore constantly. He died of a seizure 12 years later. The accident taught us much about the relationship between language, behavior and the frontal cortex, providing a basis for understanding frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

There are multiple forms of FTD. One primarily affects behavior and personality, as nerves cells critical to judgement, conduct, and empathy start degenerating. Another affects language, speaking, and writing. A third type of FTD primarily damages motor nerves; ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a form of this type of FTD. Unlike AD, memory loss and disorientation are not prominent features.

The underlying problem with FTD are abnormal deposits of either one of two proteins: one a form of tau, and one called TDP-4. The end result is a gradual loss of neurons shrinking of the brain. And unlike other forms of dementia which are seen in older people, FTD usually occurs in people in their 40’s to 60’s. An estimated 50,000 – 60,000 people in the US have the language and behavior forms of this disease. About a third are hereditary, as opposed to ALS, in which only 5 – 10% are genetic.

Recently, this form of dementia has come to the forefront as it was revealed this year that the actor Bruce Willis has FTD. Initially he presented with aphasia, a term which refers to inability to speak and to communicate with language. It was eventually determined that the aphasia due was not to a stroke, but to FTD. There is no cure for this disease, and medication help to manage the symptoms.

Delirium

There are many more forms of dementia; their diagnosis requires testing, perseverance, and a persistent, diligent doctor. Most importantly, dementia is to be distinguished from delirium, a medical term that refers to confused thinking and a lack of awareness of one’s surroundings. It is usually due to a reversible external factor, such as a disease that effects the brain, e.g. encephalitis, or a high fever; medication with mood-altering drugs, such as narcotics, sleeping pills, or anti-depressants; heavy metal poisoning, e.g. mercury or cadmium; other forms of poisoning.

Environmental factors can cause this—low oxygen or high carbon monoxide; imbalances in the body, such as low sodium; thyroid diseases; and others endocrine disorders. Nowadays, elderly patients are given multiple medications, many of which can interact and alter thought processes. When evaluating a patient for dementia, it is important to for the physician to first rule out delirium, which is usually a reversible, treatable condition. Mis-diagnosing delirium as dementia means lost opportunities for reversing this delirium, resulting in inappropriate treatment, which can be fatal to the patient.