by Michael Liss

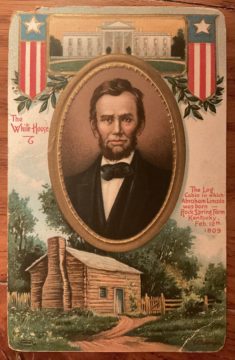

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. —Abraham Lincoln, departing Springfield, Illinois, for his Inauguration, February 11, 1861

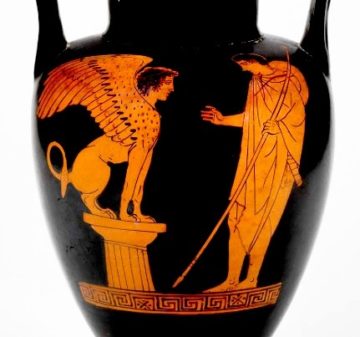

“A task greater than that which rested on Washington.” Lincoln as Oedipus? George Washington as Laius, to be slain by his son? There are a lot of myths that have sprung up around Lincoln. Some put him in the company of saints. Others, mostly coming from a Lost Cause perspective, place him a lot closer to Hades. Still, it seems a deep dive into myth to ascribe to a resentment of George Washington the life force that vaulted Lincoln from poverty and obscurity through sectional and then national prominence, then to the White House, and from there to winning the Civil War and freeing millions from bondage.

Yes, it’s the Oedipus myth, say a group of historians, including George Forgie, Dwight Anderson, and Charles Strozier. To Lincoln’s eternal damnation, he unquestionably had an Oedipus Complex, according to the renowned critic and essayist Edmund Wilson. Not so, forcefully, and even a little angrily, argue Richard M. Current, the “Dean of the Lincoln Scholars” (“Lincoln After 175 Years: The Myth of the Jealous Son”) and Garry Wills (Lincoln At Gettysburg).

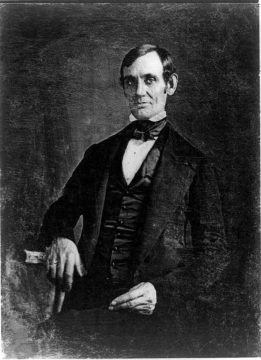

The “source code” for this dispute largely derives from a speech given by Lincoln on January 27, 1838: “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions: Address Before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. The “Young Men” part applies to Lincoln as well. He is just short of his 29th birthday, and a Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from Sangamon County. If anyone in his audience that day (besides, perhaps, Lincoln himself) thought that he might be a future President of the United States, that listener’s name is lost to history.

The speech is a young man’s oration, suitable for the era. Wills calls it “showy,” and “showy” was the Lyceum’s stock in trade. Here was a place where ambitious young men went to give and hear others give orations in the style of the time: expansive language, classical illusions, patriotism. Lincoln followed the form, and you need a little patience with the ornamentation. The relentless, irrebuttable mix of logic and passion that marked some of the best of the Lincoln-Douglas debates and his “House Divided” speech of 1858, as well as his breakthrough address at Cooper Union in 1860, were two decades away. Even further, in years and pain, were the extraordinary prose-poems of Gettysburg and the Second Inaugural.

Still, if we chip away at the more florid aspects, there is something here to take note of in both Lincoln’s framing and logic. First, we must place it in context. Lincoln’s corner of the world was on fire. Murders, lynching, and vigilantism were dominating the news. Just a few months before, the minister, journalist, and Abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy had been killed by a mob. But the violence extended far beyond those voicing controversial views and took on a life of its own. Lincoln saw the bloodlust for what it was:

Whenever this effect shall be produced among us; whenever the vicious portion of population shall be permitted to gather in bands of hundreds and thousands, and burn churches, ravage and rob provision-stores, throw printing presses into rivers, shoot editors, and hang and burn obnoxious persons at pleasure, and with impunity; depend on it, this Government cannot last.

For Lincoln, the threat was more than just to life and property, it was an assault on the system of government he and his countrymen had inherited from the Founders. Put the Lyceum Lincoln in his time. It was 1838. 51 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Andrew Jackson, who, as a 13-year-old, had served as a courier in a militia, had left office, and the last vanguard of the Revolutionary War Generation had passed from power. The “Fathers,” those great men who literally risked it all for an idea, were gone. To Lincoln, the closing of the Declaration, “We Mutually Pledge To Each Other Our Lives, Our Fortunes, And Our Sacred Honor,” was not mere rhetorical flourish. It was an oath, a bequest, and a benchmark, to be referred to again and again for the remainder of his life (we need only think of the opening lines of Gettysburg).

If the Founders did the essential work, bequeathing a bountiful land and “a political edifice of liberty and equal rights,” what were their successors’ obligations? Preservation:

‘[T]is ours only, to transmit these, the former, unprofaned by the foot of an invader; the latter, undecayed by the lapse of time and untorn by usurpation, to the latest generation that fate shall permit the world to know. This task of gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to posterity, and love for our species in general, all imperatively require us faithfully to perform.

It is from this point that the Oedipus enthusiasts take their first real leap. Lincoln seemed to voice regret that his generation would never approach that of the Founders. Preserving a legacy already given is less challenging, affording fewer opportunities for greatness, than creating one: “But the game is caught; and I believe it is true, that with the catching, end the pleasures of the chase. This field of glory is harvested, and the crop is already appropriated.”

There it is. The field of glory was appropriated. “The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others?” Lincoln’s answer was in the negative. Men may be faced with lesser or greater challenges, but their essential drives do not change.

What! think you these places would satisfy an Alexander, a Caesar, or a Napoleon?—Never! Towering genius distains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored.—It sees no distinction in adding story to story, upon the monuments of fame, erected to the memory of others. It denies that it is glory enough to serve under any chief. It scorns to tread in the footsteps of any predecessor, however illustrious. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and, if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves, or enslaving freemen.

To people like Edmund Wilson, who mourn the passing of the antebellum Southern way of life, this is catnip. Lincoln has shown himself. He saw himself as having towering genius; he thirsted for distinction; he did not wish to erect new monuments to the Fathers (particularly George Washington, the Father of the Nation). He intended to exceed the Fathers, and, through his three decades of relentless pursuit of his own ambitions, he caught them and seized their magnificent legacy for his own. By the end of the Civil War, Lincoln was the dictator he (self)-identified 27 years before. There is no “Myth of the jealous son” because it is not a myth.

It is very much worth reading Wilson’s 1962 book Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the Civil War because he is an elegant and erudite writer who uses his elegant erudition to launch a sustained attack on virtually every aspect of Lincoln’s character and performance. The Lincoln image (mostly) adopted by posterity infuriates him. Wilson’s Lincoln was a man of all-encompassing ambition who posterity has given an unearned halo: “There has undoubtedly been written about him more romantic and sentimental rubbish than about any other figure….” Lincoln was a cold man with few close friendships and limited empathy, given to abstractions, able to evaluate an idea, a tree, a political opponent, or even a woman with a clinical eye. He was “self-controlled, strong in intellect, tenacious in purpose.” The critic in Wilson recognizes that Lincoln had an extraordinary ability to communicate, especially as he refined his skills: “[H]e will always be able to summon an art of incantation with words, and he will know how to practice it magnificently.” But to what end? “[H]e has created himself as a poetic figure, and he thus imposed himself on the nation.”

“Imposed himself on the nation” is not mere rhetorical flourish by Wilson—he means it and spends a considerable amount of time flaying Lincoln for his actions both in leading up to the firing on Fort Sumter and the four brutal years that followed. He has a point, to a point, that the actions taken by Lincoln as Chief Executive at times stretched or even exceeded Constitutional boundaries, but fails to address an essential question—how would he have done it better? Instead, Wilson demonstrates an interesting moral blindness—he demands to know “Would it not have been a good deal less disastrous if the South had been allowed to secede?”

It’s not hard to infer Wilson’s answer, nor difficult to recognize his anger. He ends a chapter on Lincoln with “He must have suffered far more than he ever expressed from the agonies and griefs of the war, and it was morally and dramatically inevitable that this prophet who had crushed opposition and send thousands of men to their death should finally attest his good faith by laying down his own life with theirs.”

If that is Wilson’s final word on Lincoln, we can’t let him have it. Lincoln’s actions speak for themselves, and, if Wilson and people like him harbor animus that’s among the freedoms the Founders bequeathed to us. But the theory that Lincoln’s entire course of conduct in his public life was driven by all-consuming ambition and a hatred or jealousy of the Founders, in general, and George Washington, in specific, is built on straw.

The balance of the Lyceum speech shows it. Lincoln knew that the influence of the Founders faded with each passing year. As they departed, bonded by common experience of service and sacrifice, of common purpose and a common enemy, what Lincoln called the “living history” of their memories faded. The threat his generation (and succeeding ones) would face wasn’t just a new Caesar, it was that our nation would turn on itself, resort to the violence Lincoln saw all around him, and discard the legacy of the Framers.

At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.

How do we avoid this fate?

Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense.–Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws: and, that we improved to the last; that we remained free to the last; that we revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which to learn the last trumpet shall awaken our WASHINGTON.

The paradox in evaluating Lincoln fairly is that he possessed a sometimes-infuriating consistency. He was bounded by twin visions—the expression of freedom and equality expressed in the Declaration, and the compromises the Fathers made to get the Constitution ratified. Law, even unpleasant law, tied the two together.

You can see this emerge at Lyceum:

When I so pressingly urge a strict observance of all the laws, let me not be understood as saying there are no bad laws, nor that grievances may not arise, for the redress of which, no legal provisions have been made.–I mean to say no such thing. But I do mean to say, that, although bad laws, if they exist, should be repealed as soon as possible, still while they continue in force, for the sake of example, they should be religiously observed.

You can see it 23 years later at his first Inaugural:

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.

In that consistency is the answer to Wilson’s scolding of Lincoln for not having let the South secede:

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect, and defend it.’

It is hard to believe that Washington would have disagreed with that.