by Mike Bendzela

One tedious outcome of the ascendance of the anti-abortion movement in the United States is having to listen to the tiresome arguments about “the beginning of [human] life.” It’s like being stuck in a dentist’s office waiting for an appointment while nauseating top-forty hits from the 1970s play on a hidden radio.

Not this shit again.

Abortion is an issue my husband and I have never had, nor will ever have to be concerned about, given that neither of us has a uterus. Nor do we have children from previous engagements, who might have to be concerned about what to do with unwanted or malformed zygotes/ blastocysts/ embryos/ fetuses. But the subject is still interesting to me, given that I have existed as each of those entities at one time or another.

*

Every morning at 4:30, on cue—in darkness, in rain—a robin pipes up outside our bedroom window. One does not assume robins appear spontaneously at such moments, though it may seem like it. And upon deeper thought, one realizes The Robin has been doing this for millions of years, sans bedroom windows, imitating pre-robin ancestors who sang similar crepuscular tunes at more ancient times, ad infinitum, right back to some dinosaur’s egg.

Imagine having to rely on memory to determine when one’s life began. For me, it would be the moment I was crawling around on the floor, gumming one of the loose rubber disks the legs of my mother’s sofa rested on to prevent denting the carpet. Thus, did I begin. Cue “Sheep May Safely Graze.” There is nothing in my brain from before then; therefore, I did not exist.

Obviously, relying on memory for one’s origins is patently absurd. But it’s just as absurd that every living person celebrates their beginning as the day they were born. It is a date even I will have inscribed on a stone,

February 18, 1960 −

followed by that m-dash that gives me the willies. Truly, though, we know more about when life ends than when it begins.

Alien explorers from the third stone from Alpha Centauri would no doubt be amused by this: “Get a load of these apes: They think they begin at parturition!” We understand the birthday as a mere tradition, however, an arbitrary moment, a convenient shorthand for an uncertain beginning. That’s because dating with such precision one’s quickening, or one’s implantation, or one’s fertilization, or one’s ovulation, or whatever, would be difficult, to say the least. We verbal primates like definitive boundaries, such as clear names and dates on things, expiration or otherwise; but the curse of being speakers is that we cannot have such things, though we like to pretend otherwise.

*

At that time Mary got ready and hurried to a town in the hill country of Judea, where she entered Zechariah’s home and greeted Elizabeth. When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greeting, the baby leaped in her womb, and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit. In a loud voice she exclaimed: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear!” (Luke 1:39-42)

It was once the commonsense belief that “life” begins at quickening. Like the robin piping up outside our window, the sensation of the fetus stirring in the womb is a definitive moment for a woman, arresting her attention. And up through the 19th century, this moment was the determiner of “the right to life.”

For if a woman is quick with child, and by a potion, or otherwise, killeth it in her womb . . . this, though not murder, was by the ancient law homicide or manslaughter. (William Blackstone, 1765)

To us today, quickening is as quaint and charming a notion of the origin of a life as the day of birth is to the above-mentioned Alpha Centaurians. Surely, implantation is the more precise date, as that is when pregnancy begins. It is certainly one of the coolest moments in development because of syncytin-1. When I first learned about syncytin-1 in a course on human evolution, my head nearly exploded with wonder, like gigantic, chrysanthemum fireworks.

Over 25 million years ago, a retrovirus infected the germ line of one of our direct primate ancestors, and this retrovirus copied its entire genome into this lucky primate’s genome. (This is one of many endogenous retroviruses that make up a substantial portion of our genome.) There the virus continued being copied down the ages . . . until one day a specific sequence coding for the protein syncytin-1 became activated. This is the protein that assists the virus in fusing with the cell membranes of its host. Our primate ancestors borrowed this protein from the ancient retrovirus to become an essential element in the development of the placenta, leading to a physical fusion between mother and fetus unlike any other in the mammalian class. Gaining syncytin-1 was like driving down a highway and having a winning lottery ticket blow into your window.

Imagine: A fetus bonding with its mother’s uterus is like a virus binding to a host cell!

Syncytic-1 aside, implantation, too, is a slippery “moment” to deem the onset of “life,” given that much occurs before this stage and 40-60% of embryos don’t survive beyond it. I guess we’ll have to search further back in time along the great chain of development.

*

Today, many mark “the instant of fertilization” as the beginning of human life. This is the new “quickening.” But that, too, is a hoax, for there is no “instant” of fertilization. After being ejaculated, the sperm migrate to the Fallopian tubes, whereupon a few of them gang up on the newly-ovulated oocyte, effectively digesting its envelope to allow one—and only one—of their buddies to enter. Everything but the nucleus of this single sperm gets stuck outside the envelope, and it enters and piles its 23 chromosomes† next to the 23 of the ovum. But even this is a process, involving meiotic divisions, followed by a mitotic division that fuses their chromosomes. No bell rings, no harps swell, no corks pop, as the rapidly dividing zygote begins its week-long journey towards implantation.

When would this mythic beginning have been in my case? Wikipedia says, “The average time [from fertilization] to birth has been estimated to be 268 days (38 weeks and two days) from ovulation, with a standard deviation of 10 days or coefficient of variation of 3.7%”. Or:

May 25, Give or Take, 1959 –

I call this candidate for the “beginning of human life” a hoax because neither gamete—sperm nor oocyte—could possibly be considered not living, not human. If they’re not living or human, then what are they? About points of origin, Stephen Jay Gould notes, “Look for something in the middle, and you find nothing but continuity—always a meaningful ‘before,’ and always a more modern ‘after’.”

Some argue that a “unique human being” arises from the fusion of these chromosomes, but this is the worst sort of reductionism (which I’m generally all for). Pointing to a knot of chromosomes and calling it a human being is like pointing to a page of Baking With Julia and calling it a Crème Brûléed Chocolate Bundt. Much needs to take place in the interval before the oven timer goes off.

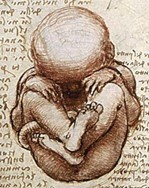

In the case of human ontogeny, there are those gill arches, limb buds and tail that need to be dealt with first before a person arises.

*

OK, Smarty pants, some may remark, so when does life begin, then?

It doesn’t.

This is not the answer most want to hear. But, echoing Gould, no point of origin presents itself in life’s continuum, and language attempting to name such origins always fails us. Every ovum comes from an unbroken, living line of predecessor ova dating back millennia. Every one, though genetically haploid, is as human and as alive as every one of us. These ova carry the mitochondrial DNA—which is separate from the nuclear DNA—of our direct female ancestors, inherited largely intact from a single line originating in East Africa about 200,000 years ago and thus functioning as a powerful tool for identification of descent.

But it doesn’t end there. One might say this buck never stops (or perhaps I should say “doe”) but continues back through all haplorhine, or dry-nosed, primates; back, egg-by-egg, through all the nocturnal, tree-living, insect-eating Euarchontoglires cowering at the sight of dinosaurs; back to the synapsids striding through coal swamps 300 million years ago; to earlier eggs deposited in water by mysterious tetrapods during the Devonian; and back, back to fish, hagfish, lancets, our mothers all, until we arrive somewhere 3.9 billion years ago, give or take, when we were all enfolded in a single, procaryotic dot, not much unlike my zygote headed for implantation on what seems like only yesterday.

Such uncertainty and complexity around the origins of life leads me to conclude that the best position to take on the issue of abortion is to mind one’s own business.

_______________

† This essay is dedicated to my dad, who entered hospice care at the time of writing.

Images

1. Zygote. Nina Sesina. 2018. Wikipedia Commons.

2. From “The female external genitalia and five views of the fetus in the womb.” Leonardo Da Vinci. Public Domain.

3. Human embryo, 7th week of pregnancy. Ed Uthman, MD. 2006. Wikipedia.