by Tim Sommers

In “Shower of Gold” by Donald Barthelme, Peterson, a sculptor who welds radiators together, applies to be on a TV show called Who Am I? – strictly for the money. In the ensuing interview, he asks the interviewer, Miss Arbor, what the show is about.

“‘Let me answer your question with another question,’ Miss Arbor said. ‘Mr. Peterson, are you absurd…’

“’I beg your pardon?’

“‘Do you encounter your existence as gratuitous? Do you feel de trop? Is there nausea?’

‘‘’I have enlarged liver,’ Peterson offered.’

“‘That’s excellent!’…Who Am I? tries, Mr. Peterson, to discover what people really are…Why have we been thrown here, and abandoned? …alone in a featureless, anonymous landscape, in fear and trembling and sickness unto death. God is dead. Nothingness everywhere. Dread. Estrangement. Finitude. Who Am I? approaches these problems in a root radical way.’”

“‘On television?’”

“Most people feel on occasion that life is absurd, and some feel it vividly and continually,” writes Thomas Nagel.

What does “absurd” mean? Various dictionaries say, unreasonable, inappropriate, incongruous, laughable; from the Latin “absurdus”, which literally means “out of tune”. Nagel says the absurd involves “a conspicuous discrepancy between pretension or aspiration and reality.” “This is what you want. This is what you get,” as the song goes (“The Order of Death,” Public Image Ltd).

Here are Nagel’s examples of absurd events. “Someone gives a complicated speech in support of a motion that has already been passed; a notorious criminal is made president of a major philanthropic foundation [or the United States]; …as you are being knighted, your pants fall down.”

But it’s one thing to say that particular events in our lives are absurd, it’s another to say, as Nagel and Camus (among others) do, that life on the whole, life overall, is absurd.

Again, what makes life, or anything absurd, is not the thing in and of itself, but some contrast, discrepancy, some out of tune-ness. “I said the world is absurd, but I was too hasty,” Camus says. “This world itself is not reasonable, that is all that can be said. But what is absurd is the confrontation of the irrational [with the] wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart. The absurd depends as much on [us] as on the world.”

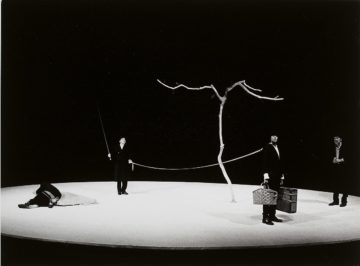

Sisyphus is Camus’ way of explaining why life as a whole is absurd. Sisyphus is condemned by the gods to eternally roll a boulder to the top of a mountain, only to have it roll down again every time. Our lives, according to Camus, are no less futile. We, too, struggle mightily at tasks that, from any distance at all, seem meaningless. The trick is, Camus says, to understand how Sisyphus – and we – might still be happy. Camus is deadly earnest. “There is only one really serious philosophical problem,” is his opening line, “and that is suicide.”

(On a personal note, I saw a puppet show based on Sisyphus at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, and it was just as punishing to watch as pushing a boulder up a hill would have been to do – and also seemed to go on eternally. I believe it was my punishment from the gods for having chosen to go to a puppet show.)

Nagel thinks that the “reasons usually offered” for thinking that life in general, and not just particular events in it, are absurd “are patently inadequate.”

Here are the kinds of reasons he rejects. We are going to die. The universe is large and old and we are small and short-lived. Life is meaningless or purposeless.

Start with: We’re all going to die. That doesn’t make life absurd. Something meaningful is not made meaningless by coming to an end. It’s not absurd that we don’t live forever. Nor is it clear that making our lives longer would make them more meaningful – and, anyway, how long would they have to be to be meaningful? The universe is nearly fourteen billion years old and may exist for as long as three trillion years (which means, by the way, that we live in the very early part of the universe with two trillion nine hundred and eighths-six billion years or so go.)

Which brings us to: The universe is very large and very old, while we are very small and won’t last long. Would life be less absurd if we were so large that took up a significant fraction of the universe? What about time? It’s not time, in and of itself, that is worrying, I think. It’s this. Nothing we will ever do will matter to anyone even a little way into the future – nor will it matter to almost anyone else even right now, much less far away in the vast ocean of time. But that’s alright. Something has to be meaningful to you now and here. If it doesn’t matter here and now, then who cares if it matters in the distant future or to people far away? Looking elsewhere for the meaning of life, for example, looking to other lives (or an afterlife or aliens or the singularity) to justify this one, creates an infinite regress – and I’m afraid its turtles all the way down.

Even the idea that life seems to be have no overall purpose or meaning doesn’t make life absurd, unless you already expect life to have some such meaning. Which, perhaps unfortunately, we do. Remember what Camus said. You can’t call the world absurd just because it seems to lack any rhyme or reason from our point of view. What’s absurd is that, even knowing this, we can’t give up on demanding reasons, meaning, something.

Nagel has a slightly different take. The tension is between thinking what we do is important, but knowing that from a more objective perspective that it’s not. He says, “We cannot live human lives without energy and attention, nor without making choices which show that we take some things more seriously than others. Yet we have always available a point of view outside the particular form of our lives, from which the seriousness appears gratuitous. These two inescapable viewpoints collide in us, and that is what makes life absurd. It is absurd because we ignore the doubts that we know cannot be settled, continuing to live with nearly undiminished seriousness in spite of them.”

Fair enough. But I have another question. What, if anything, is the relationship between irony and absurdity? Is life ironic, as well as absurd? Or is there something ironic about the absurdity of life?

Sorting people into generations to make generalizations is basically astrology – with generations as Zodiac signs. Nevertheless, here I go. I am a founding member of Generation X (born in in 1965, the same year as Douglas Coupland, author of “Generation X”). As such, I can’t help but think that, despite Dave Eggers’ insistence that “there is almost no irony, whatsoever” (in his book “A Heart-Breaking Work of Staggering Genius” or) our generation, something about my generation is captured by the claim that we have, more than anything else, an ironic view of the world.

(Here’s an example of the ass-backwardness of generations-talk, by the way. When I was in high school, we were all supposed be a bunch of little Reagan Youths and Alex P. Keaton’s, and then there was a recession and, suddenly, coincidently, we were all “slackers”. By the same type of coincidence, Millennials are all a bunch of job-hoppers by nature, in the era when more and more jobs are temporary and/or uncertain.)

Anyway, I have some trepidation about taking on irony. I don’t want to be yelled at by Dave Eggers. Nor do I want the Alanis Morrissette treatment. She says she been harassed for over twenty years by people who say that none of the examples of irony in her song “Ironic” are ironic. How thorough has been “the shaming” (her words)? There’s a Broadway musical out now based on her album, “Jagged Little Pill”, which features one character saying of the examples in “Ironic” that “That’s not irony. That’s just, like, shitty.”

(On the other hand, imagine that a guy played the lottery all the time. Isn’t the fact that as “An old man [who] turned ninety-eight, [he finally] Won the lottery, and died the next day,” ironic? Don’t cha think?) (There’s also a theory that says what was ironic about the song “Ironic” is that there’s intentionally nothing in it that’s ironic.))

Anyway, there are at least three kinds of irony. Verbal irony, basically, sarcasm. Theatrical irony (either dramatic or comedic), where the audience/reader/viewer knows something the character(s) don’t – to comic or dramatic effect. Then there’s situational irony. Sometimes defined as a striking reversal of what is expected, other times as an incongruity between expectations and what actually happens.

I think people have too crimped an understanding of situational irony. I’m talking to you Dave Eggers. You once footnoted the line “Footnotes are not ironic*” with “*What the f*** is ironic about this?” Which is ironic, dude, because it’s a striking reversal of what’s expected from a footnote. But maybe Eggers is a step ahead and he knows he’s always ironic, while denying it. (Is that ironic?) But he seems pretty mad about being called ironic. But, I’m on my third “but”, “The reason…our pervasive cultural irony is at once so powerful and so unsatisfying is that an ironist is impossible to pin down.” David Foster Wallace.

Anyway, I think situational irony is meta-absurdity. The absurd thing is that we expect, demand, and crave meaning from life, even though we are always aware, at least peripherally, that from a larger perspective, we can’t really believe, or at least can’t prove, that life actually has any meaning. But it’s ironic because when this absurdity continually gets away from us, which it inevitably does, and when we catch up to it again (or it catches up to us), we experience it as a drastic reversal of our expectations. Again, and again. The absurdity is experience as ironic. Irony about the absurdity of life is more or less absurdity on a higher level. As I said, meta-absurdity.

For that matter, when we look at other people’s lives, we experience almost theatrical irony in the absurdity of life. While they are engaged with life, thinking of it as meaningful, we can see that from a larger perspective it is not. To dramatic or comic effect?

What can we do about the fact that, ironically, life is absurd? Camus imagines Sisyphus happy. But how?

“It is more fitting for a man to laugh at life,” says Seneca the Younger, “than to lament over it.” But I think we can do better than that.

Here’s Peterson on “Who I am?” After they humiliate the first two contestants, one, for example, by pointing out that the karate lessons he took that helped him thwart a robbery were paid for by his impoverished mother who couldn’t really afford them, Peterson thinks “I was wrong…the world is absurd….” Then, “On the other hand, absurdity is itself absurd.” So, he goes on offense.

“’In this kind of world,’ Peterson said, ‘absurd if you will, possibilities nevertheless proliferate and escalate all around us and there are opportunities for beginning again. I am a minor artist and my dealer won’t even display my work if he can help it but minor is as minor does and lightning may strike even yet. Don’t be reconciled. Turn off your television sets,’ Peterson said, ‘cash in your life insurance, indulge in mindless optimism…How can you be alienated without first having been connected? …

“The little red light jumped from camera to camera in an attempt to throw him off balance but Peterson was too smart for it and followed wherever it went. ‘My mother was a royal virgin,’ Peterson said, ‘and my father a shower of gold. My childhood was pastoral and energetic and rich in experiences which developed my character…’ Peterson went on and on and although he was, in a sense, lying, in a sense he was not.”