by Bill Murray

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet.

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet.

“Pull the strops around your west,” explains the flight attendant.

We’re leaving now though, en route to Dakar, rumbling along a bumpy, corrugated taxiway. We pull up to wait, curious about the glint of the other jet coming in. Turns out it’s full of whoever comes to Bamako on Royal Air Maroc.

Mali is scrub. It’s brush. It’s Sahel, hot as hell. We lumber into the air around eleven o’clock and we have spent one hour and seventeen minutes in Mali. Look down on Gambia and what do you see? Gambia the river glinting below the wing, Gambia the country a pelt of land on either side, itself gobbled up by Senegal, except where the river debouches to the sea.

•••••

One New York Times correspondent, on arriving in Dakar, wrote about “responding to being in a deeply unfamiliar setting.” Heard that. A less politically enlightened twenty years before she did her tour, as a young man in 1995, I hated Senegal in a rolling and keening way, but I only hated it about half as much by the time we left.

It wasn’t the Senegalese, who were most gracious. We were just worn out, buffeted by a howling, furious three month round-the-world endurance run, on which Senegal was country 23. Maybe it wasn’t the best idea to leave West Africa for last.

Because what do you know? Big West African cities can be unsettling for skinny white American first-timers in white socks and preposterous khaki shorts (me), just the same as for those florid American package tourists arriving for their first package safari all tricked out in LL Bean safariwear (You know who you are. On second thought, probably no, you don’t).

My first Africa visit, in 1989, I saw a fight spill right out into traffic in downtown Nairobi. Walking back from a newsstand, I nearly stumbled over a fistfight right in the middle of Kenyatta Avenue. Pushing and shoving and a man’s shirt torn from his chest.

Fear bears no fruit, I told myself, stepping as judiciously (and quickly) as I could around the pile of people to take a perch in the famous tourist bar at the New Stanley Hotel called the Thorn Tree, a place that at the time I found the height of discernment.

Teju Cole wrote about being new in an African town, in his case Lagos: “I see another fight, at the very same bend in the road. All the touts in the vicinity join this one. It is pandemonium, but a completely normal kind, and it fizzles out after about ten minutes. End of brawl. Everyone goes back to normal business. It is an appalling way to conduct a society, yes, but I suddenly feel a vague pity for all those writers who have to ply their trade from sleepy American suburbs, writing divorce scenes symbolized by the very slow washing of dishes.”

So this is life vividly lived? Well, maybe. West Africa is not East Africa and it’s not a tough town like Abidjan, Dakar is not, but I have yet to learn how to stop petty thieves, touts and thugs from sapping my enthusiasm, and they are rife here.

We booked ourselves into a fancy hotel on a point out west of Dakar on Cap Manuel near Plage de l’Anse Bernard. Senegal is the westernmost African country and we perched on its western tip.

You take your confected drink from Mister Matthew, all bowtie, girth and good humor, and walk your blistered pink American legs out to stand in the sand behind him and burn your toes on the closest sand to the Americas on the continent. Which doesn’t get you any closer to home.

You take your confected drink from Mister Matthew, all bowtie, girth and good humor, and walk your blistered pink American legs out to stand in the sand behind him and burn your toes on the closest sand to the Americas on the continent. Which doesn’t get you any closer to home.

In mathematics, they say, you cannot be lied to. Unlike in Dakar. The published cab rate to the city, right up there on the wall by the bell boy, declares 3000 CFA. The taxi guys all swear to Allah hell no really it’s 6000. I jawbone right back with asperity, half really perturbed, half theatrical, not wanting to get off to a patsy’s start, trying to come on like I’ve got a belly full of battery acid but weary of having to go round and round just for a ride.

(Most people think they’re smarter than average. I do too, of course. But I fell straight into a ruse the other day in the much more mercenary Côte d’Ivoire: the local boys made like officials who were going to open a new pass control lane for you, confiscated your passport straight off the plane and expedited you to a row of clerks, arrogant as barristers. Which required a tip to get your passport back.)

Our friend Nick, a Peace Corps volunteer, knows we’re coming, and we look forward to a familiar face, maybe a night on the town. Nick’s number rings in to the Peace Corps office; he has been in town but is headed back to his village by p.t. (public transport). We leave our contact details in room 105.

Room 105 is suffering from a city water strike right now, far as we can tell. A lovely, dear staff delivers buckets of water to the door. They are unfailingly kind while losing select bits of our laundry, especially my wife’s colorful shirts. It’s okay, really. If you have a business meeting and they lose your dress shirt, problem. If they lose your only pair of pants, problem. In this case, on holiday, no problem.

•••••

Worn down. Need air tickets home. Somewhere way back around Bulawayo my remaining strength crossed its arms and turned its back. Now, on emotional tiptoes, we find a travel agent on Place de l’Independence who further thumbscrews our immiseration: we can not leave today for anywhere. We can go to Casablanca Friday or Monday, Paris Sunday, and we just missed today’s Madrid flight. Et c’est tout.

Dull as ditchwater and with commensurate ambition, we commiserate at a bar around the corner where Calvin and his junior colleague from Liberia profess to be diamond smugglers. Here’s my number in Monrovia, just call my secretary.

When my wife Mirja is away, Calvin confesses he has something very confidential he’d like to talk about with me tomorrow, when I am not so busy as we obviously are today. After studying my shoes for a time, I say, give us a call. No wait … I’ll call you guys.

After we get significantly into upper lip stiffener at that bar we rise and march impromptu around the corner through the curio peddlars and tummy-trimmer (as seen on TV) vendors toward the ferry terminal. The Ministry des Affaires Étranges sort of glitters on the corner, with a late model gray sedan in front. Windshield cracked.

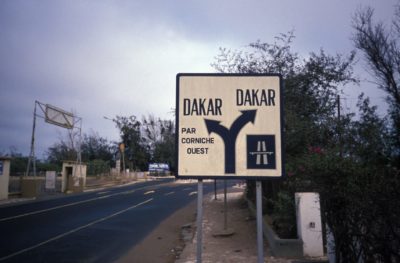

Five shining minutes of walking and not being accosted feels damned good. Dakar might be all right. Down this avenue to Boulevard de la Liberation you gotta juke through the Total gas station parking lot, from which bush taxis bound for all over Senegal leave, to get to the Gorée Island ferry. Through Portuguese, Dutch, English and French regimes over three hundred years, Gorée was the largest slave warehouse on all of Africa’s west coast.

Nosing out through the commercial port, the breeze feels fine in your hair but the ship’s horn causes me to jump out of my seat as we pass the fisherboys on the waterbreak. Nerves shot.

Nosing out through the commercial port, the breeze feels fine in your hair but the ship’s horn causes me to jump out of my seat as we pass the fisherboys on the waterbreak. Nerves shot.

Aboard ship Mirja gains a “sister,” a woman in a colorful flowing robe whose girth invites metaphors of generosity. She is a bead merchant I’ll wager will be hard to detatch without a purchase. Ile de Gorée is only about three kilometers offshore.

In 1995 at least, Gorée Island’s 1000-odd residents lived blissfully unburdened by the weight of slave trade history, the precise weight that visitors today come to strap on their backs, lug around and hold close.

We walk across the island and back; it’s about 70 acres, doesn’t take all day. The ferry ship, the Blaise Diagne, makes another trip, returns, and we let it go yet again and sit to take it all in. A beautiful woman with a dazzling white smile wrapped in brilliant orange won’t let us take pictures unless we buy a Fanta. Fair enough.

Toubabs (white people) sun on the beach on the far side of the ferry pier where pirogues are for let. We sit at Café Restaurant le St. Germain because Mirja’s ‘sister’ grabs her by the hand and walks us over there, having spied us halfway across the island.

Oh, and we are such nefarious toubabs. Still we do not buy beads. We sit outside at little picnic tables on sand, drink Flag beers and bat flies. All cold drinks sweat into pools of water on the tables, so they come with little blue terrycloths to soak up their glasses’ sweat. The server brings additional coasters to use on top of, not under, our beers. The sun beats down but it seems it is never hot in coastal Senegal.

Five boys sit side by side, dangling a fishing line. I consider the idea that fishing is less about catching the fish than freeing the fisherman. That may speak well of fishing, unless you’re the fish. A fine commentary on Gorée, these boys appear utterly free in the first place.

Mirja buys beads from her sister on the ferry home. As part of the deal she has three strands of hair braided with two little beads at the bottom.

Mirja buys beads from her sister on the ferry home. As part of the deal she has three strands of hair braided with two little beads at the bottom.

•••••

Time congeals, clots, won’t progress. The hotel’s “laundry factory” still hasn’t delivered our clothes. The water is off. It will not be possible to eat just now. Order a beer. Deal with it. Flush with buckets.

Rick with the Peace Corps calls to say that Nick won’t be back until tomorrow, but would we like to do something with him? This is so sweet and yes, any other time. He is new in town, needs a friend, but this time sorry, no, we’re have got to sleep.

An hour later the phone rings and it’s Nick. He is in town. He catches a cab and marvels at the hotel. Didn’t know such a thing existed in Senegal. Let’s go into town to a real restaurant.

If you walk down the street beyond the hotel you can catch a cheaper cab, at people’s prices, but it turns out there are no more cabs, and we end up walking the entire corniche through the kind of pitch darkness Burundians call “who are you” nights, when it’s so dark even your shadow won’t stand beside you.

Nick gets his bearings at Avenue Pasteur and steers us onto Soweto Square, Avenue Nelson Mandela. The national assembly is here. I think it doesn’t look bad and Nick agrees. He says it looks better at night. You can’t tell the paint is peeling.

Somewhere behind us is the President’s house but Nick isn’t sure where. He may be the tallest head of state, Nick thinks, and I guess well, that’s something. Arusha, Tanzania just then was advertising itself as the halfway point between Cairo and the Cape. In the same way, I guess that’s something too.

We say we saw one man in particular on the way to the ferry who was so tall, so fierce, he scared the hell out of us. Mighta been the president, Nick says.

These tall ethnic Wolof fellows conjure menace with their elaborate, flowing neck to floor robes, called mbubb, imported to French as boubou. The Wolof share their formidable height and these effective robe affectations, oddly, with Omanis. Emerge into Muscat international airport’s arrivals taxi rank and you will find Omanis, statuesque and inscrutable, towering above you in similar flowing robes, augmented with sabres.

The first place we go in, everybody knows Nick but tonight they don’t have the dish he wants us to try, so he promises to eat lunch there tomorrow, gives hugs around, and we move on down the street, beside Jihad Coiffures, to Restaurant VSD Plus, Chez Georges, number 91, Rue Moussé Diop.

They pour water from mineral water bottles but for sure it’s tap water. In a wan and wisened tribute Nick reckons it’s good. They recycle the bottles. Nick orders, and keeps answering, “Wow.” He isn’t overawed. Waaw is Wolof for yes.

Nick lives in Segatta, three hours by p.t., with a father, three mothers and countless brothers and sisters. His family gets a small stipend to keep him. Says he’s learned patience. Doesn’t feel he needs TV and AC like he used to. Nowadays does a lot of waiting. Reading. Is working on digging latrines for the locals.

He came here to plant things, an agricultural volunteer, but because of the ongoing drought his assigned mission is pointless. Barren as it is out there, as soon as they put a seed in the ground a bird eats it. So instead he digs latrines. His expectations are lower now. On a good day he writes a letter.

Some of his best friends are prostitutes. Usually they had child number one at 13 or 14 and now they aren’t prime wife material, just down-on-their-luck, sweet girls. They and Nick just hang out.

A few days’ beard, a little longer than average hair, blue flannel shirt and jeans and an old Atlanta Braves hat. Mirja thinks he’s good looking. Remember, it’s the 1990s. Nick doesn’t smoke in his village so the kids won’t see him. He’s setting an example. Instead he sneaks Skoal.

He’s proud of his two years in Senegal. He has learned some Wolof. He’s glad he didn’t pack it up and leave, although he wanted to lots of times. But also, unequivocally, he says he will not re-up. Terms are 27 months (the first three in training) and his tour ends in about four months.

Wants to write a book about a guy in advertising who leaves the U.S., joins the Peace Corps and moves to Senegal. At that point it becomes a novel, he says, because nothing has happened in real life that would be compelling enough for a book.