by Tim Sommers

I had a weird reaction to Charlie Huenemann’s recent 3 Quarks Daily essay on knowledge. I mean I disagreed with him that knowledge is a “policy to live by” (as I’ll explain later), but that wasn’t weird (and, of course, I could just be wrong). No, the weird reaction that I had was to his aiming at a nontechnical account of knowledge shorn of all the philosophical jargon (if that is what he was doing, I took it that way). Anyway, it immediately made me want to defend the jargon and wonky bits of epistemology.

Epistemology, by the way, is what philosophers call the study of knowledge.

See, here is the thing. In the end, either all the jargon and moving parts of epistemology are not really necessary to explain knowledge. In which case, epistemologists should just knock it off and talk like the rest of us. Or that jargon, and that kind of analysis, is what you need to really get at what knowledge is. In which case, cutting all that is a genuine loss.

I say loss. The best way I can think of to defend that claim is to defend a supertechnical, up to the minute, jargon crazy epistemologist’s definition of knowledge. I believe you will understand me. Let’s give it a try.

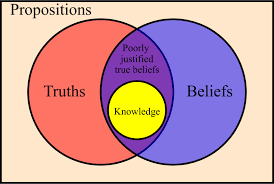

Knowledge is (1) Gettier-proofed (2) justified (3) true (4) (propositional) belief (5) with no undefeated defeaters.

One thing first. I totally agree with Huenemann about the complete uselessness of using capital letters or “really” to qualify any philosophical account of any x. Philosopher’s don’t study “Knowledge”, with a capital “K”, as opposed to knowledge (Thanks a lot for that one, Rorty. You started it.) Philosophers capitalize words (or don’t) according to the same rules of grammar that apply to everyone and, like most people on the internet, philosophers find gratuitous capitalizing a red flag. Furthermore, the only time it adds anything to ask what we really know, as opposed to what we just know, is when we are robbing a bank. In that case, we might say, ‘Do you really know the silent alarm didn’t go off?’ But then “really” is just a way of asking how sure you are. What we really know is really just whatever we know and vice versa.

So, what’s knowledge? Huenemann is right that it’s a kind of belief. To know something, you have to believe it, right? And it seems like beliefs are propositional. If you believe something, then there is something like a sentence, “That car is blue”, that you believe. You can’t just believe “blue”. Or car. You can see blue and see a car, but the belief that car is blue is sentence-like thing; that is, propositional. What exactly is a proposition? That’s too much for this article. But a proposition is basically the meaning of a sentence. So, there’s (4).

What kind of belief is knowledge? It’s true belief. There’s (3).

Here then the first part of my criticism of Huenemann. Knowledge is not just true belief. One reason why is that if that were true then anybody who had any kind of crazy belief that they had no sane reason to have in the first place would have knowledge if that belief, wholly by accident, turned out to be true. If a hundred years from now some scientist finds a way to kill COVID by shining a kind of light inside of your body or feeding you bleach, then, hey!, Trump knew all along you could kill COVID that way. Or suppose you had a brain tumor that caused you to have all kinds of delusional beliefs. Suppose one of those delusional beliefs is that you have a brain tumor. Is that knowledge? Can you know you have a brain tumor even if it is completely undiagnosed and you have no non-delusional reason to think so?

What’s lacking is a connection between the belief and what makes it true. What’s lacking is the true beliefs being justified. There’s (2). Knowledge is justified true belief. So, here’s the rest of my criticism of Huenemann. He goes right from “true belief” to knowledge as “getting things right – really right”. Now, I thought we agreed that this “really” business is not helpful, but focus on this instead. Knowledge is not getting things right. A perfect performance in a gymnastics event gets it right, I would think. But it’s not knowledge. Maybe, he means “gets it right about what to believe”. But, see, that is just a homey paraphrase of being justified. I say knowledge is (at least) justified true belief. If have sufficiently good reasons to believe something, and it’s true, then I have knowledge (or almost (see below)).

In truth, I don’t really know what’s going on with this “beliefs as policy” thing. Maybe, it’s some kind of pragmatism? But no matter how strongly I adhere to a belief, that doesn’t make it knowledge. In fact, it seems scary to me to replace the idea of being justified with just being really insistent. We have too much of that already. You don’t get to have your own “knowledge” policy. You are entitled to think that your firmly held beliefs are knowledge, but you are not entitled to us agreeing with you. It’s a you can have your own opinion, but not your own facts type of situation.

In fact, there is more to knowledge even than justified true belief. Can you prove this is not a dream, or that you are not in The Matrix, or not a brain in a vat, or that the universe wasn’t created five minutes ago along with lots of misleading evidence (your memories, for example) that it had been around a long time? These are defeaters. They are distressingly easy to come up with. And they tend to reflect their era. Right now, for example, the most popular defeater is that the world we live in is someone else’s computer simulation. It used to be that this is all a dream. It seems that if any defeater is true then most of what you believe – except maybe about your own immediate sense perceptions – is false. If you know how to defeat all the defeaters please let me know in comments. My gut says that it can’t be that in order to know anything we have to rule out all possible defeaters, but so far everyone I have talked to says my gut is wrong. So. I don’t know.

What about this Gettier-proofing business? Suppose I believe that my Cali Classic 125 light blue scooter has been, and is, parked behind the philosophy building since the pandemic started. I parked it there. I drove past it later and saw it there. I know it’s there. But what if it was stolen? And after it was stolen I won a lottery that I had forgotten about entering and they dropped a light blue Cali Classic 125 in the spot mine used to occupy? So, I have a true belief that that my bike is there, and it’s even justified. But given that the bike that is there is a completely different bike, it seems like I don’t have knowledge – even though I have justified true belief. [Fun fact. These examples, which are easy to come up with once you see the structure, were introduced in in a three-page paper by Edmund Gettier in 1963. Arguably, on a per-word basis, therefore, easily the most influential philosophy paper of the twentieth century.]

We can’t really get into it, but here are a couple of ways to deal with Gettier counterexamples in general. Maybe, you can just fix up “justified” so that it covers these cases. Or maybe we need to add (as I do here) a separate condition, but one bolstered by a general account about how to respond to these. I think these counter-examples are interesting, but hardly a crisis. But then again, I’m not an epistemologist.

No, the problem in my opinion with epistemology isn’t Gettier or that it’s too technical or hard to understand. The problem with epistemology is all those defeaters. The problem is that many of our most influential epistemologists are still mired in Cartesian skepticism (i.e., again, for example, how do you know we don’t live in The Matrix?). They believe that you can only have knowledge of your own immediate sensations. That’s a problem. But it’s not a too-technical, jargony, not for popular consumption problem. It’s just a quite easy to understand, actual philosophical problem.

Take it seriously and see what I mean. How do you know that you are not, right now, inside a simulator? How do you know that I am not using this article as a way to reach you in your artificial slumber? Maybe, my real message is this. Wake up. Wake up to the real world.

Just kidding. Here’s one way to defeat all the defeaters. Maybe, justification isn’t just about what’s going on in your head. Maybe, it shouldn’t be “internalist”, but “externalist”. One kind of externalist view is reliablism. According to most reliablist, knowledge is true belief “caused by a reliable mechanism”. Belief is made true then by being the product of said reliable mechanism – not by our justifying it. One weird thing about that is that I don’t always know if I have knowledge because I don’t know if a belief I have was the result of a reliable process or not. So, this sort of solves the defeater issue, since the real world’s existing guarantees many of our beliefs about it are true, but it doesn’t solve the old-fashion defeater problem because it doesn’t tell us whether the relevant beliefs are in fact true or not. But I think we should stop now. Thank you if you made it this far. Please, share your thoughts in comments. Even if you didn’t read this part.