by Tamuira Reid

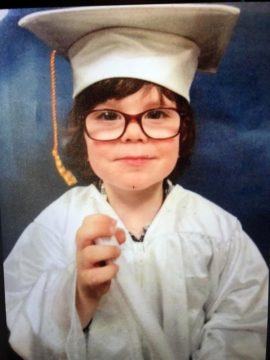

This is my son, Ollie.

This photo was taken five years ago. It’s one of my all-time favorites because of the look of absolute pride on his face. Hard-earned pride. I realize that pre-k graduation isn’t the most celebrated of milestones for a lot of families, but for us it was huge; Ollie was about to go mainstream.

Looking back at that little boy, and reflecting on the kid he is now, I feel lucky that we live in a city like New York. A city that has endless resources, creativity, spirit, hustle. The city that has taught us what it means to be humble, be grateful. A city that has afforded my disabled son access to an equal and appropriate education, and a public school with teachers who have loved and unconditionally supported him. A city that knows how to rally.

This is my son, Ollie.

Currently a proud in-coming fourth-grader, but with the same coke-bottle glasses and wide, generous smile. His backpack is usually absent-mindedly left open, and is stuffed with graphic novels, half-eaten bags of flaming hot Cheetos, a stress ball, and various contraband (slime, hotwheels cars, Skittles to share on the bus with potential friends, Pokemon cards to trade although he hasn’t figured out exactly how). As he passes you during drop-off, he will greet you with a “Good morning!”, maintaining direct eye contact, something that still feels, at times, unnatural to him.

Ollie Duffy doesn’t really walk from point A to point B, because the “electricity” running through his body, as he’d tell you, is hard to control. His movements are a little bit “more slippery” and unpredictable, like a sideways skip/grapevine type of thing, until he inevitably trips over his own feet. And even though he knows where he’s supposed to go, he often forgets mid-journey.

If Ollie sees your child crying, he will try to comfort them. Usually with a hug, sometimes with a Skittle. If that doesn’t work, he’ll sit nearby so they don’t feel alone. If Ollie is in class with a bully, he’ll feel sorry for them because being angry can mean you’re just frustrated, and he knows how that feels.

This is my son, Ollie.

Heart as big as the planet.

I started giving him his $5 weekly allowance in singles, at his request, that he hands out one by one to the homeless people that we pass on our morning walk, from the B train on Sixth Avenue to Hudson Street. “Nobody should have to live outside,” he’ll tell me, his glasses fogging up.

Ollie has marched for Me Too, for Black Lives Matter. He makes his own signs although I help spell certain words. He has danced his way through nine Pride Parades, held by the kindness of strangers. He’ll dance, he says, until every member of the LBGTQ community is afforded the right to decide who and how to love, and to have that love be counted.

He has written postcards to “The Government” arguing that affordable housing isn’t really affordable at all, and that all essential workers should have federally-funded Hawaiian cruise packages for their service.

(I don’t think he knows that much about Hawaii, other than people seem to like it a lot.)

He is a self-proclaimed feminist and fan of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He is anti-bomb and pro-peace and cries whenever Michelle Obama makes a speech. I have watched him stock shelves at food banks, clean-up dog shit at animal shelters, and carry the winter blanket off his own bed to a man who sleeps on a park bench in our Brooklyn neighborhood.

Ollie cares about all people, regardless of what they look like, what they have and don’t have, where they come from. It’s an innate quality that I wish everyone had. He is a better human than me. I am learning from him constantly and thankful for his ability to make choices based on his strong moral compass. He makes me check myself. And he just turned ten.

What do you think Ollie will say when I tell him that there were people out there in a position to help him – and other kids like him – but they chose not to? How do you think that will make him feel?

This is the very real conversation NYC parents with special learners have been forced into having with their kids. The it’s not you, it’s them pep talks, every morning of every remote day. The hundreds of you are not stupid’s and nothing is wrong with you‘s when they can’t find an answer to the problem, to the equation, to not falling out of the chair. The heart-to-hearts about their categorically indisputable otherness, the differences in brain and body that both sparkle and brutally define. The types of conversation that should never have to happen in the first place, that the Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act is meant to prevent.

There are over 220,000 students with disabilities in the NYC public school system. My son is one of them. His first word – hiiii – didn’t come until he was nearly three years old, but when it did, we both lost it. I cried because the sound of his voice as it formed around that word was the moment I knew he’d be okay, he would make it. And he cried because it plain shocked the hell out him.

Since then, I’ve learned to navigate the Special Education system by way of the Department of Education; this is an ongoing, often grueling and frustrating process. I have had to learn what is afforded to my child by law, under the Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act, and to identify when his civil right to an “equal and appropriate education” (IDEA) has been violated. Together we have weathered the storm of the Early Intervention experience and subsequent clinical evaluation and diagnostic tests (beginning at age 2), secured a spot in a center-based preschool after having to apply and go through a harrowing vetting and admissions process, have attended dozens of IEP (Individualized Educational Plan) meetings with teachers, specialists, social workers, and DOE representatives, have benefitted from endless hours of therapy and interventions by fantastically devoted, skilled, and dedicated educators, and ultimately transitioned to a public school special education program with an ICT (Integrated Co-Teaching) classroom designation on his IEP.

Needless to say, this has not been an easy road. As a mother, I’ve had to watch my son work his ass off, to the point of complete mental and physical exhaustion, at an age when other kids were enjoying playing in the sandbox. A DOE-appointed behavioral therapist would show up at our apartment at 6 am, to help get through the process of simply getting dressed for school, which often took a good two hours of trial and error. And you know what? Ollie has never felt sorry for himself. He has never complained. He’s made sacrifices and adjustments to his childhood routine that no child should have to make, and he’s done it with grace, determination, and diligence. And the reason for this is quite simple: the kid loves to learn. Not the stuff a parent teaches – the daily talks about this and that, the conversations about the way the world works – he enjoys that, but I’m talking about straight-up academics, math and reading, writing, science, all of the lifelines of information that have finally opened up to him because of his IEP and the special education teachers who have given him access to his own, beautiful brain.

Sadly, after going remote last March, I have watched this joy for learning disappear with each new day. I’ve witnessed an unraveling, a steady and powerful regression that has me up most nights worrying, scared for my child, knowing all too well how precarious his situation really is. It is so easy to forget your child is learning disabled when they are doing well. If anything, remote/hybrid learning has only reacquainted me with the gaps in Ollie’s cognitive processing, and the number of ways in which his mind just closes shop if left to its own devices.

Imagine years of watching the learning steadily and carefully progress; years of therapy and services and tutoring giving way to words, to an entire language, to a way of communication with outside world; years of shapes and numbers finally adding-up, problems becoming do-able, even fun; years of pinning every birthday party invite to the fridge because you still remember a time when there weren’t any. Now, imagine all of this being nearly wiped-out within one calendar year. This is the rate of regression that students with disabilities are experiencing; they are being erased from the educational landscape with each minute of remote learning that passes.

Having an IEP is not only about receiving services, should the need be there – speech, occupational therapy, physical therapy – it is also about, and perhaps even more about being in an ICT classroom with a teacher who is trained in special education. These students need in-person teaching and instruction just by way of the very nature of their disabilities; speech and language delays, auditory processing disorders, Autism Spectrum Disorders, dyslexia – and that is just a handful of the disabilities children with IEP’s have. They need skilled professionals to offer different ways of engaging and keeping them on task, alternative methods of teaching the same grade-appropriate curriculum. An example of this would be a child with ADHD, which by definition “impacts attention and executive function”. A child with ADHD often requires constant redirecting to stay on task, and this is given by someone who has been trained in not only recognizing the signs of distress, anxiety, and cognitive fallout, but in appropriately and efficiently addressing them in the moment, in real time, in person so they do not fall behind. Often the signs of regression are most visibly read in their body language, which cannot be read through a computer screen. And this is only one example of how in-person teaching is an absolute necessity to disabled students.

IDEA includes thirteen categories for what is considered a disability. Thirteen.

And what if this child comes from a working single parent, single income family? Or both parents work away from home and don’t make enough money to cover the cost of a tutor-sitter-helper, let alone buy into a pod, where many students aren’t only learning, but are socializing as well?

The problem NYC schools now face is patching together an equitable re-opening plan for the fall. 1-2 days per week of reduced hour, in-person instruction is not nearly enough, for any student, but especially in the case of special learners. This means that unless schools reopen five days a week for in-person, students with an IEP will remain largely untaught. Their educational experience has been, and will continue to be unequal and inappropriate. NYC has the highest number of students in special education programs in the nation, and yet, here we are, shutting them out of the classroom all over again.

This is a problem of privilege. Of a privileged union that weaponizes children in an ongoing battle to settle their grievances with the state. Of the privileged parents and teachers, unwilling to let go of what is theirs, of what they are entitled to, what they deserve. Of politicians and leaders too far removed to even begin to understand the needs of the very people they are charged with protecting.

By fighting to keep NYC schools closed – or by sending typically-developing kids back to school at a ratio the same as disabled learners – an elitist, culturally negligent learning system stays in place. These students are not asking for anything more than what their abled peers already have; access to an education.

The Individuals with Disabilities Educational Act has roots in the same civil rights movement that gave life to groundbreaking decisions such as Brown vs. The Board of Education. How can you pick and choose which civil rights to defend? Which poster goes up in your window? What sort of example is this setting for our kids? That you only step up and make noise if it won’t hurt you? That you will “rally” as long as it doesn’t interfere with your own privilege or political agenda and aspirations?

What would you tell my son – and all the 220,000+ children with disabilities in the NYC public schools system – if you were face to face with him? How would you rationalize the decision to use your privilege against him as he handed you his last Skittle?

We are the largest and most diverse school system in the nation, one that other districts are looking at for guidance, for inspiration, for ideas. Instead of setting the bar high, we have gone low. And dragged the children down with us.