by Philip Graham

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

I’ve long been partial to Portuguese culture, so when Portugal transferred its last colonial holding, Macau, back to Chinese rule in 1999 , a friend surprised me with his marveling reaction: “Portugal had an empire? Who knew?”

Perhaps his reaction shouldn’t have surprised me. In the United States, steeped as we are in the history of the United Kingdom’s “empire on which the sun never sets,” few are aware that the Portuguese accomplished the first European globe-spanning empire, beginning in the 15th century.

When I lived in Lisbon for a year, I noticed that my Portuguese friends wrestled with the legacy of their country’s history. They felt pride at the achievements of their intrepid ancestors’ global reach. But they also felt shame, because while all empires break too much before they reshape the chaos they created, Portugal’s empire was especially bad.

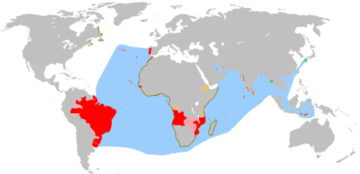

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

The Portuguese initiated the transatlantic slave trade in 1444, which has bedeviled and tormented much of the world ever since. Sixty years later, the Viceroy Alfonso Albuquerque expanded Portuguese power not only as exploration for economic reasons, but as a brutal crusade against Islam. By 1580, the empire extended from Brazil to Africa, from India to Malaysia and on to the Indonesian island of Timor.

So what happened to this Portuguese empire, which now no longer exists?

The Nobel prize-winning author José Saramago took a stab at answering this question in his novel, Memorial do Convento (in English, Baltasar and Blimunda). Rather than invest the empire’s great wealth in the country’s infrastructure, a succession of Portuguese rulers instead built palaces and churches. Perhaps the most egregious of these projects was the enormous Convent of Mafra. Over 13,000 Portuguese laborers and craftspeople died in the construction of this majestic and essentially useless building—a tragedy that doesn’t approach the uncountable death toll of African slaves in Brazil who mined the gold to gilt it.

The Nobel prize-winning author José Saramago took a stab at answering this question in his novel, Memorial do Convento (in English, Baltasar and Blimunda). Rather than invest the empire’s great wealth in the country’s infrastructure, a succession of Portuguese rulers instead built palaces and churches. Perhaps the most egregious of these projects was the enormous Convent of Mafra. Over 13,000 Portuguese laborers and craftspeople died in the construction of this majestic and essentially useless building—a tragedy that doesn’t approach the uncountable death toll of African slaves in Brazil who mined the gold to gilt it.

This one project alone, completed in 1730, nearly bankrupted the government. When an earthquake utterly leveled the city of Lisbon in 1755, the country weakened further. By 1822, Portugal had lost Brazil to an independence movement, and over the years lost other, smaller, colonial holdings to the steady encroachments of another rising empire, Great Britain.

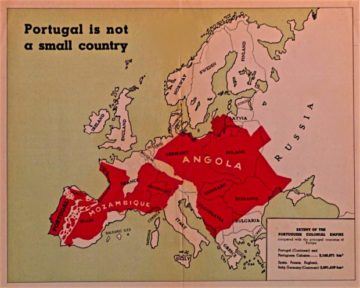

By the 20th century, Portugal had become one of the poorest countries in Europe. Yet illusions of empire die hard. A stunningly presumptuous yet popular map displayed during the 40 years of fascist rule under António Salazar, “Portugal Is Not A Small Country,” showed the dictator’s idea of Portugal enhanced by the addition of its remaining African territories, thereby stretching from Europe’s southern Atlantic border all the way to Russia. Finally, in 1974, the Portuguese people and the army, wearied and bloodied after decades of war against African independence movements, rose up in a nearly bloodless revolt—the “Carnation Revolution”—and ended the dictatorship. In short order, democracy was restored at home and the African colonies were finally granted their hard-fought freedom.

By the 20th century, Portugal had become one of the poorest countries in Europe. Yet illusions of empire die hard. A stunningly presumptuous yet popular map displayed during the 40 years of fascist rule under António Salazar, “Portugal Is Not A Small Country,” showed the dictator’s idea of Portugal enhanced by the addition of its remaining African territories, thereby stretching from Europe’s southern Atlantic border all the way to Russia. Finally, in 1974, the Portuguese people and the army, wearied and bloodied after decades of war against African independence movements, rose up in a nearly bloodless revolt—the “Carnation Revolution”—and ended the dictatorship. In short order, democracy was restored at home and the African colonies were finally granted their hard-fought freedom.

And yet, out of five centuries of imposed misery abroad, and the slow, painful decline at home, a distinctive and vibrant culture arose. Nearly 300 million people now speak Portuguese in the ten countries that constitute what is known as the lusophone world (a name derived from the ancient Roman word for Portugal, Lusitania). What was once imposed by power now lives on in powerful cultural ties. A well-read member of the lusophone literary world, for example, would be familiar not only with the Portuguese writers Fernando Pessoa and José Saramago, but also José Eduardo Agualusa of Angola, Clarice Lispector of Brazil, Mia Couto of Mozambique, and Cape Verde’s Germano Almeida, to name just a few.

The same connections extend to cuisine, as if the lusophone world is one enormous and delicious cookbook. I serve as the family cook, and one of my go-to kitchen references is Cuisines of Portuguese Encounters, by Cherie Y. Hamilton, which is packed with 500 years-worth of culinary crossovers. Where else can I find a recipe for Bibinca, an East Timorese dessert “of Goan origin that the Portuguese took to Timor”? Or Picadinho, a kind of hearty breakfast hash that Portuguese Jews, fleeing the Inquisition, brought to Brazil? Or Bahian fish stew (Moqueca de Peixe) that combines the cooking traditions of Africa and Brazil’s indigenous Tupi-Guarani?

The same connections extend to cuisine, as if the lusophone world is one enormous and delicious cookbook. I serve as the family cook, and one of my go-to kitchen references is Cuisines of Portuguese Encounters, by Cherie Y. Hamilton, which is packed with 500 years-worth of culinary crossovers. Where else can I find a recipe for Bibinca, an East Timorese dessert “of Goan origin that the Portuguese took to Timor”? Or Picadinho, a kind of hearty breakfast hash that Portuguese Jews, fleeing the Inquisition, brought to Brazil? Or Bahian fish stew (Moqueca de Peixe) that combines the cooking traditions of Africa and Brazil’s indigenous Tupi-Guarani?

And then, there’s the limitless variety of lusophone music. Let’s start with Portuguese fado.

While fado (the Portuguese word for fate) is considered the archetypical Portuguese musical form, going back to at least the beginning of the 19th century, it’s really a combination of North African melismatic singing, West African blues, Roma and Jewish song and the deep Portuguese gift for melody. Which is not a surprising combination, since the birthplace of fado is believed to be in the Lisbon quarter of Mouraria, one of the most multicultural neighborhoods in the city.

Amália Rodrigues, whose career spanned much of the seemingly endless 20th century Salazar dictatorship, has long been considered the queen of fado, embodying through her vocal art the deep Portuguese feeling of saudade—an untranslatable word that contains within it sadness, nostalgia, longing, and perhaps a regretful tenderness. Today, the widely acknowledged heir to Amália’s crown is the singer Mariza. Born in Mozambique to a Portuguese father and Mozambican mother, Mariza moved with her family to Lisbon, where she grew up in Mouraria.

Here Mariza sings, in a voice of restrained passion, “Meu Fado Meu,” (in English: “My Fado, Mine” or “My Fate, Mine”—or both, actually). The orchestration is arranged by the Brazilian cellist Jacques Morelenbaum, and the confluence of Brazil, Mozambique and Portugal in this fado song is a further example of the syncretic nature of this musical genre. The lyrics, too, refer to the wider lusophone world:

I sing an endless country

The sea, the land, my fado

I bring fado into my song

and my soul is saved

*

Another artist who exemplifies the brilliant music that has risen from the embers of empire is Virginia Rodrigues. She was born in a favela in the city of Salvador, the heart of Afro-Brazilian culture. In “Uma História de Ifá” (“A History of Ifá”) she sings of the town of Ejibo in Nigeria, one of the religious centers of Ifá, which became the basis of Candomblé in Brazil.

Change is not one thread but a cord of many. Portugal’s crimes of forcibly transporting enslaved Africans to Brazil (nearly five million souls) also inadvertently brought about the birth of a new religion: Candomblé, which combines Yoruba deities (orishas) of Ifá with the Catholicism of Portugal, as well as indigenous Indian beliefs and even aspects of Islam.

Change is not one thread but a cord of many. Portugal’s crimes of forcibly transporting enslaved Africans to Brazil (nearly five million souls) also inadvertently brought about the birth of a new religion: Candomblé, which combines Yoruba deities (orishas) of Ifá with the Catholicism of Portugal, as well as indigenous Indian beliefs and even aspects of Islam.

Though Rodrigues was discovered through her singing in church, she is a follower of Candomblé. When she sings of her religion, of a sacred city across the ocean, her deep voice—which can also soar to stratospheric heights—creates an atmosphere of awe and peace, as if summoning unseen orishas:

Shining city,

Ejibo,

Flowered city,

Ejibo,

Ejibo, enchanted city,

Ejibo, its true majesty

*

The ten deserted islands that came to be known as Cape Verde were discovered three hundred miles off the coast of West Africa by Portuguese explorers in 1456. These islands were quickly populated—with enslaved Africans, their Portuguese overlords, and Jewish conversos (forcibly converted to Catholicism) trying to build a life far from the Inquisition back in Portugal. Over the course of five hundred years Cape Verdeans have developed a singular mix of European and African culture, including their linguistic marrying of Portuguese and West African languages, called Kreol.

Cape Verdeans are mad geniuses of music. I’ve traveled to three of the islands—São Tiago, Santa Antão, and São Vicente—and everywhere an unusually large number of home-grown musical styles are played: morna, coladeira, funaná, batuque and more. On the streets of Mindelo, the main town of São Vicente, it’s impossible to walk more than two blocks without hearing music from a park, a club, a balcony, or the open windows of a home, as if the very air is scented with song.

Cape Verdeans are mad geniuses of music. I’ve traveled to three of the islands—São Tiago, Santa Antão, and São Vicente—and everywhere an unusually large number of home-grown musical styles are played: morna, coladeira, funaná, batuque and more. On the streets of Mindelo, the main town of São Vicente, it’s impossible to walk more than two blocks without hearing music from a park, a club, a balcony, or the open windows of a home, as if the very air is scented with song.

Singer and songwriter Mário Lúcio was born on the island of São Tiago, the largest of the islands that make up the archipelago of Cape Verde, and he grew up near the town of Tarrafal, the site of a notorious prison during the years of the Salazar dictatorship. Lúcio could be called Cape Verde’s renaissance man. He not only founded and led the legendary band Simentera, he is also a poet, playwright and novelist, and for five years he served as Cape Verde’s Minister of Culture.

In his song “Kreol,” Lúcio sings about how Cape Verde’s blended culture, now a source of great national pride, was originally the result of the back-and-forth of the slave trade, accomplished “in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.” However, Lúcio sings, this holy invocation can’t erase other words:

In the hold of the ships

You would hear the sorrow of them crying:

Oh my mother,

Oh my mother….

*

Aline Frazão, a singer-songwriter born in Angola, can claim an Angolan, Cape Verdean and Portuguese family heritage. She now lives in Lisbon, and in the accompanying video here she performs in an intimate space at B. Leza, Lisbon’s premier club for the diversity of lusophone music. The club is named after Francisco Xavier da Cruz, nicknamed B. Leza (beleza is Portuguese for “beauty”), who is considered one of the greatest Cape Verdean composers of the slow and soulful songs known as morna.

Frazão’s song celebrates the Angolan dry season—the cacimbo—which brings lower temperatures and cooling mists after the grueling heat of the rainy season. Yet for centuries this dry season has held a particular, grim meaning for Angolans.

Frazão’s song celebrates the Angolan dry season—the cacimbo—which brings lower temperatures and cooling mists after the grueling heat of the rainy season. Yet for centuries this dry season has held a particular, grim meaning for Angolans.

Soon after Angola’s independence from Portugal in 1975, a civil war began between rivals Jonas Savimbi and Holden Roberto, one that would continue for another 25 years. In the first months of that war, the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski (as recounted in Another Day of Life) asked Ndozi, a military commander, what he thought of the initiation of hostilities so soon after independence. “We didn’t want this war,” Ndozi replied, and he then proceeded to give Kapuscinski a somber history lesson:

“This country has been at war for five hundred years, ever since the Portuguese came. They needed slaves for trade, for export to Brazil and the Caribbean and across the ocean generally. Of all Africa, Angola supplied the greatest number of slaves to those countries . . . . This was once a populous, settled country and then it was emptied, as if there’d been a plague. Angola is empty to this day. Hundreds of kilometers and not a single person, like in the Sahara. The slave wars went on for three hundred years or more. It was good business for our chiefs. The strong tribes attacked the weak, took prisoners, and put them on the market. Sometimes they had to do it, to pay the Portuguese taxes. The price of a slave was fixed according to the quality of his teeth. People pulled out their teeth or ground them away with stones in order to have a lower market value. So much suffering to be free. From generation to generation, tribes lived in fear of each other, they lived in hatred. The military campaigns took place in the dry season, because it was easier to move then. When the rains ended, everyone knew that the times of misfortune and of hunting for people had begun. In the rainy season, when the country was drowning in water and mud, hostilities stopped. But the chiefs were thinking up new campaigns, marshaling new forces. This is remembered by everyone even today because, in our thinking, the past takes up more space than the future.”

Aline Frazão’s song, performed here a decade after the end of Angola’s modern civil war, looks at the dry season not as a season of warfare, but as a time of welcome relief from the punishing heat of the rainy season, its cooling winds a gift to those who labor all day under the sun.

But Frazão then goes farther, equating the cacimbo with the soothing consolations of art—as art can also “cool the head that burns” and can, perhaps, bring about more than individual peace. A way, perhaps, to think of the future as often as the past.

If the cacimbo comes to soothe

Each step’s slow weight

on the meager path

Burning from working in the sun

Cacimbo makes the day easier

Gives shade, consoles with art

Cools the head that burns

And comes, comes

Comes to soothe …

As Frazão sings her nimble, swaying song, you might notice a telling detail in this relaxed club scene. Through the wide glass wall behind Frazão, the graceful arched lights of a bridge shine in the night’s darkness. It’s the 25 de Abril bridge—named after the day in 1974 when the people of Portugal overthrew 40 years of dictatorship, a revolution leading directly to the independence of the country’s African colonies, including Angola.

There’s another detail you might have missed. On the couch behind the keyboard player sits a young woman, gently transported, nodding her head fondly, her lips silently mouthing the lyrics, as if she has each weaving contour of the song memorized.

Sometimes, when I watch this video, I can’t keep my eyes off her appreciation. She seems to embody the emotions I feel when listening to the music of Brazil, Portugal, Cape Verde and elsewhere. There’s a particular amalgam of joy and sadness, regret and hope that seems to run through song after lusophone song, like an underground river.

*

Portugal is a small country. Its north to south length is less than, for example, the distance between the relatively neighboring Brazilian cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, while the population of Portugal is a third that of São Paulo’s alone.

Yet during Portugal’s heady European Union days of the early 2000s, many of the people who lived in those countries that once made Portugal fictionally the size of Europe moved to Lisbon and throughout the rest of the country. In a way, the former empire squeezed itself back into the true tiny size of Portugal, hefted it up internally, bringing along renewing versions of the country’s culture.

“Se Essa Rua Fosse Minha” (“If This Road Were Mine”) is a perfect example of how the Portuguese have enthusiastically adapted and adopted the rich and diverse musical cultures they inspired. This song, a sweet Brazilian lullaby, usually receives a gentle, hushed interpretation.

If I stole your heart

It’s because I love you

If I stole your heart

It’s because you stole mine too.

But here, the Lisbon-based band OqueStrada delivers a delirious version, playing this Brazilian lullaby at a breakneck speed inspired by the rhythms of Cape Verdean funaná, and the Portuguese audience, often so restrained in public, lets loose its joy.