by Liam Heneghan

In Memoriam Tim Robinson (1935 – 2020) and Máiréad Robinson (1934 – 2020)

In Connemara: Listening to the Wind (2006), the first volume of cartographer and writer Tim Robinson’s trilogy of books about that rugged part of Co. Galway, Robinson records an illuminating and slightly fraught exchange that he had with landscape artist Richard Long about the fate of the artist’s work left exposed to the battering Irish coastal elements.

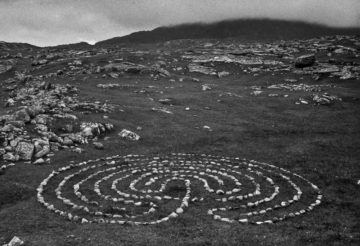

Work of Long’s include pieces sculpted from rocks and other materials found as he traversed natural landscapes on foot. The sculptures are gradually re-arranged by forces in the landscape, though the images have greater durability and are often displayed in galleries and preserved in archives.

In his excursus about Connemara to complete his trilogy, Robinson located one of Long’s sculpture on a small headland near the town of Roundstone The piece, entitled Connemara Sculpture (1971), is comprised of beach pebbles arranged in a distinctive pattern. This was not the first of Long’s pieces that Robinson had located and mapped. As a gift for Long, Robinson’s wife Máiréad had sent Long a copy of a map on which Robinson had marked a couple of pieces on Inishmore, the largest of the Aran Islands.

Long took umbrage to the gift, writing to Robinson that he was “very surprised and aghast when someone told me years ago that my work was marked on a map.” It had not been his intention, he went on to write, for the sculptures “to be marked sites.” Long concludes his letter to Robinson noting that fortunately the “map that you kindly sent… didn’t have my sculpture on it.”

Robinson—that consummate map-maker—replied to Long, pointing out explicitly where these sculptures were marked on the map. Of course they were mapped!

Along with Robinson’s spirited defense of the fidelity of his mapmaking, he makes the following point: “…once the artist has made an intervention in the landscape and left it there, it contributes to other peoples experience of place, which may well be expressed in someone’s else work of art.” He goes on to write, “…your marks on the landscape will have a career of their own; they are no longer defined by their origin in your creativity.”

Writing about Connemara Sculpture, Long has remarked that the pebbles on a beach recorded the artist’s reaction to an antique rock carving that he had seen in a Dublin museum a week before his Connemara visit. Long’s photograph of this sculpture was subsequently exhibited at the Tate museum (until very recently it remained on their website). Twenty years or so after the pebbles comprising the Connemara Sculpture had been placed, their form remained relatively intact and provoked the interest of Robinson, who in his turn, included it in his art: on his map (as Long’s pieces on Inishmore had been) and in his writing about Connemara.

Knowing this story, and since I visit Roundstone frequently, I wondered if Connemara Sculpture is still there, nearly fifty years after Long created it, and a decade or so after Robinson wrote about it. Perhaps I could rediscover that work, or perhaps through the work of the elements or the mischief of humans, the pebbles are now scattered and the sculpture is gone.

And so I searched. Despite a long day on the dunes in June 2018 (with my wife and some friends), and matching the landscape as best we could against all the pictures I had of Connemara Sculpture we could not find any trace of it.

Where the sculpture had been, now is a cow pat—a monument in its own way to ephemerality.

Knowing that it was once there and is there no longer may be satisfying enough.

So is this a fitting end of Long’s sculpture? The elements comprising the work have been scattered as Long intended. Yet we might be arrested by Robinson’s rejoinder to Long, that once the artist has abandoned the work, the work endures on its influence on the work and lives of others.

Despite Long’s irritation that the map made the sculpture a marked site, he and Robinson were not that far apart in their thinking. After all Robinson’s intention to map and write about these sculptures (more description can be found in Stones of Aran: Pilgrimage (1986)), does not conflict with Long’s intention for the piece. In pointing to, and reflecting upon a sculpture that is no longer there Long’s ambition is fulfilled, and Robinson’s task as chronicler is discharged.

Though the sculpture is “gone,” the term “gone” is an ambiguous one: the story of Long’s traversing that landscape lingers, and there are stones aplenty all around, some of which I may have even photographed.

A work whose presence slowly becomes an absence performs a special type of work. The pattern of beach pebbles continues its conversation with the winds and the rain—the pebbles are there, though the sculpture may not be. Connemara sculpture has now become a form of signage pointing out its former location: “This is the place where Richard Long’s Connemara Sculpture once was.” The stones will inch away from each other without concession to any human intention other than the one that views all human aspirations as vanity.

Robinson, and his wife Máiréad, passed away in this pandemic year of 2020: a loss that seems monstrous to those of us who enjoyed their hospitality over the years. It consoles me that Tim Robinson employed the episode of the finding and recording of Connemara Sculpture to remark in his writing on the putresibility of all things. Tim concludes, “This is how we make room, make time, make the world for ourselves. This is the gargoyle-logic of creation.”

Decay is how each generation makes way for the next. Contemplating the gargoyle-logic of creation seems philosophically exciting when discussing pebbles on the dune in Roundstone, Co. Galway. Contemplating how we make way, and make time is a more bracing task when we contemplate what we have lost this past year.

***

Liam Heneghan is Professor of Environmental Science and Studies at DePaul University. He tweets @DublinSoil. Many thanks to Angela Stenberg for comments on a earlier draft of this essay.