by N. Gabriel Martin

Is it still possible today, in the age of widespread and outlandish conspiracy theories, algorithmically induced filter-bubbles, and bullshitting demagogues, a generation after the US Republican party adopted a strategy of unprincipled obstructionism to anything that their democratic counterparts proposed, to believe that reason has a place in politics? When we are so polarised that finding any relevant common ground with our opponents at all is a far-fetched notion, it seems naive to think that it is still possible to move politics by making good arguments. If that were true, then there would be nothing more to politics than might making right. However, pessimism about political reason is only partially justified. While our ability to resolve political disagreements using reason is in crisis, other aspects of public debate are more vital than they have been in generations.

In the aftermath of the breakdown of the political consensus that dominated the broadcast era and persisted for a while into the internet age it is hard to be credulous about resolving disagreement by appealing to opponents’ reason. It’s not possible today, as it once was, to appeal to a common ground of faith in political and cultural institutions in order to bring opponents over to one’s side. The fragmentation and polarisation of the media landscape, contests over the validity of governmental institutions (such as the courts or elections) previously widely considered neutral, and denial of the credibility of experts have left us without much common ground. That’s true, even though we still share many beliefs and values. Politicians and commentators from across the political spectrum talk about the same values, such as democracy, freedom, and life, but on their own, without shared institutions to provide a common understanding of what threatens and what nurtures those values, shared values themselves are too hollow to help us resolve conflicts. The current battle over the legitimacy of the election shows how defence of a grand and nebulous value like democracy can be claimed by either side. Without trust in the expertise and neutrality of institutions, it is impossible for most of us to determine which purported threats to democracy are real and which are fake.

The bygone political consensus occasionally allowed us to resolve our differences using reason. There are some important examples of this over the past fifty years, and each of them has a place among the greatest disasters of that time. Take, for example, the argument that the welfare state needed to be rolled back in favour of a callous and cruel regime of austerity. Broadcast media’s willingness to parrot right-wing claims and assumptions about the iniquities of welfare, from the racist myth of ‘welfare queens’ abusing the system, to the (also racist) myth that welfare creates a “culture of dependency” that leads people to be work-shy facilitated the bipartisan efforts to reduce or eliminate the social safety net in the US and in the UK, begun under Democratic and Labour governments in a spirit of pragmatism, and then zealously pursued by more right-wing Republican and Conservative governments.[1] In the case of the US, the Democratic party, under the leadership of Bill Clinton, oversaw the near elimination of welfare in the form of cash assistance with the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

There are many other disastrous bipartisan policies that were facilitated by the defunct era of political compromise: the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the expansion of the carceral state, to name three.

This is what we have lost today—the possibility of relying on common ground, shared beliefs and shared worldviews, in order to resolve our differences. But, as these examples from the 70s to the 2000s show, the ability to reason with political opponents tended to make things worse, not better. The lamented possibility of achieving consensus on controversial issues was often to our detriment. It would have been better if there had not been bipartisan agreement about the need to do away with welfare and to invade Iraq; if the dissent had been louder, more widespread, more enduring, and the consensus weaker.

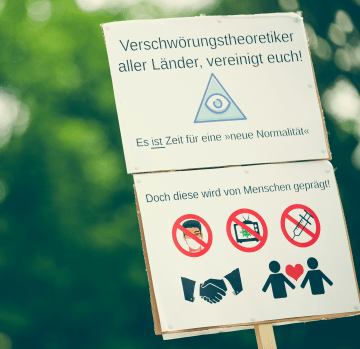

I want to keep these serious failures in mind as we look at the legitimately worrisome breakdown of an admittedly disastrous political consensus, because recognising the damage done by a vicious consensus is crucial to accurately assessing the dangers (and perhaps even hidden opportunities) raised by its decline. What is most alarming about political discourse today is the increased popularity and empowerment of what had been relegated to the fringes—outlandish conspiracy theories, barely veiled racism, and cynicism about democratic institutions. If some of these are new in their particular iterations (QAnon, for example), as general outlooks they are not new at all. What is distinctive about their place in politics today is that instead of being relegated to the fringes, they are embraced by a sizeable minority of the populace and by political leaders (far too many for comfort).

However, these views remain in the minority and their impact on policy so far remains minimal. As annoying as it is that President Trump is able to trample institutional norms without losing his core support, it is worth remembering that most people disapprove of his corruption and despotic power-grabs. Also, with some important exceptions, these out-there departures from the norm have not done much yet to steer public policy away from the avenues already laid out, and into new and more harmful directions. Trump may court QAnon followers, and both take advantage of and encourage cynicism towards democratic institutions, but much of the policy he has overseen—his tax cuts, deregulation, and Federalist Society-backed judicial appointments—has not been out of line with the neoliberal political consensus. Two major exceptions are his response to COVID-19, which encouraged denial of scientific expertise and institutions, and his crackdowns on immigration and refugees. However, the latter was not a complete departure from the country’s history of restrictions on non-white immigration, and a (mostly) steady trend towards stricter immigration controls since the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act.

I do not mean to say that the ways that political discourse is developing in the social media age aren’t legitimately worrying, only that we should keep a sense of perspective when we consider the warning signs of a more authoritarian and dysfunctional turn. In order to develop perspective, we have to understand the vices, as well as the virtues, of the social order that we are worried about losing. Although the breakdown of the broadcast era consensus has made room for worse and more hateful ideas to gain popularity, keeping an eye on and pushing back against these new developments should not come at the expense of recognising the, so far vastly more harmful, political consensus that the broadcast era fostered, and which we still live with.

That is why I reject the sense that political reason has become worse off, even though it is obviously nearly impossible to come to an agreement. Before we lament the loss of the ability to make common cause, we should look at what the era of compromise has wrought.

This may sound like a pessimistic conclusion—that reason is not in decline simply because it was not in ascendancy before—, from which an even more pessimistic conclusion can be derived—that political rationality has never been anything but a myth. However, that pessimism is warranted only as long as we gauge our reasonableness according to the prospects of resolving disagreements through rational argument. Fortunately, reason is not only nurtured by forging paths to the resolution of conflicts, it is also nurtured by the discovery of new or previously hidden truths and the refutation of previously accepted falsehoods. With that in mind, the social media age offers a lot of grounds for excitement and optmism.

The multiplication of media sources and publishers that has allowed wild and baroque conspiracy theories to spread, and made it easier for ideologically committed racists to organise and communicate, has also allowed progressive political groups to organise and facilitated the spread of information that, unlike QAnon conspiracy theories, is not at all baseless, but has nevertheless been limited in the broadcast era (information about the plastics and beverage industries’ efforts to deceive the public about the recyclability of their products, or about the FBI’s efforts to infiltrate and subvert anti-war, feminist, and civil rights groups,[2] for example).

The unravelling of the broadcast era consensus has brought important criticisms to the fore, made space for new and different questions and issues, and allowed a greater diversity of perspectives to emerge. This democratisation of the media environment provides the conditions for enormous cultural epistemic progress. Blogs, podcasts, imageboards, YouTube channels, Facebook groups, tweets, and memes offer a far more diverse media landscape. Diversity and democratisation has allowed issues that would have remained private in another era to become matters of public concern. This proliferation of voices, media, and ideas does not facilitate resolution of debates, on the contrary, it multiplies the questions up for discussion, and the positions taken on them, but there is no denying its benefits to public understanding.

For the most part, the developments in public discourse that are worth celebrating have not come in the form of newsworthy revelations, either. In fact, the news media has always been fairly well equipped to break stories. The social media era, though, is good at shifting our attention. In particular, the proliferation of opinion writing on blogs, podcasts, and YouTube videos do not break stories, they consist of argumentative discourse that urges us to adopt a given perspective or interpretation, or reconsider what matters. Protest movements also work to draw attention to an issue or group of issues.

The New York Times broke the story that there had been accusations of sexual harassment against Harvey Weinstein for decades (and later, The New Yorker reported on accusations of rape against the producer), but only a movement like Me Too could draw attention to its importance. A popular protest movement was necessary to bring public awareness to the importance of the issue. If there an important issue is neglected, then bringing attention to that issue is a crucial development in our understanding.

What do we learn from this? This is not a recipe for political or rhetorical success, or even for philosophical success (as long as the latter is conceived in the sense of getting at the ultimate truth of the matter). What it means, though, is that we are still able, and more able now than ever, to talk to each other meaningfully, to listen to each other, and thus, to reason together. If reasoning together today is less likely to result in agreement, that is not such a bad thing. Even if it is harder to talk to each other, that does not mean that it is not still worthwhile, maybe even more worthwhile. A transformation of discourse which raises more questions, or even causes confusion about which questions we should be asking or arguing over is not necessarily a bad thing for public discourse or understanding. If we are to take public debate seriously, that means being open to disagreement, and not only as long as it can be quickly settled.

[1] David Garland. 2016. The Welfare State: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[2] Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall. 1990. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States. South End Press.