by Charlie Huenemann

H. G. Wells’ novella, The Time Machine, traces the evolutionary results of a severely unequal society. The Traveller journeys not just to the year 2000 or 5000, but all the way to the year 802,701, where he witnesses the long-term evolutionary consequences of Victorian inequality.

The human race has evolved into two distinct species. The first one we encounter is the Eloi, a population of large-eyed and fair-haired children who are loving and gentle, but otherwise pretty much useless. They flit from distraction to distraction and feed upon juicy fruits that fall from the trees. “I never met people more indolent or more easily fatigued,” observes the Traveller. “A queer thing I soon discovered about my little hosts, and that was their lack of interest. They would come to me with eager cries of astonishment, like children, but, like children they would soon stop examining me, and wander away after some other toy.”

The Traveller is an adventurous explorer in the mold of Richard Francis Burton or Henry Walter Bates, so he is eager to begin theorizing about how the Eloi came to such a state. He is struck by the fact that the Eloi are nearly androgynous, and he thinks that both this fact and their docility must have resulted from a life in which there is no need for struggle.

“I felt that this close resemblance of the sexes was after all what one would expect; for the strength of a man and the softness of a woman, the institution of the family, and the differentiation of occupations are mere militant necessities of an age of physical force. Where population is balanced and abundant, much childbearing becomes an evil rather than a blessing to the State; where violence comes but rarely and offspring are secure, there is less necessity—indeed there is no necessity—for an efficient family, and the specialisation of the sexes with reference to their children’s needs disappears. We see some beginnings of this even in our own time, and in this future age it was complete.”

So the manifest difference the Traveller sees in his own time between “the strength of a man and the softness of a woman” is the result of hard lives that require a division of labor: there is he who hunts, fights, and protects, and she who nurtures, comforts, and suckles. When life becomes as easy as eating the fruit that drops from the trees, these differences are erased, and everyone becomes – well, pansified, as someone from Wells’ time might say. They skip about in silken robes and are frightened by even the faintest show of force. Snowflakes, as it were.

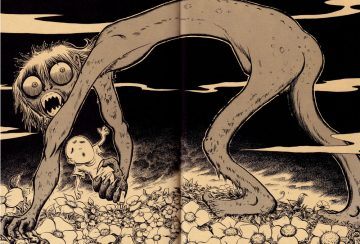

But it’s not true that the Eloi face no challenge. For every dark night they are preyed upon by the dreaded Morlocks, the other descendants of our species. These troglodytes live in subterranean tunnels and tend to run on all fours like apes. The Traveller does not have too much difficulty defending himself against a few of them, but in large numbers they become a terrible, carnivorous army. And they are devious: in a climactic scene they set a trap for the Traveller, who escapes only because he has the miracle of (now ancient) technology on his side.

The Traveller does not get as much time to observe the Morlocks – to see whether they are sexually differentiated, or possess a language or any native curiosity. He is too busy beating them back with a club. But this does not stop him from theorizing that the Morlocks have descended from industrial workers, forced to live their lives in dark mines and factories until any light at all became impossible to bear. So they sealed themselves off from the overworld and propagated their species in dark, ignorant places, and became what someone might well call deplorables.

Over the millennia the Morlocks, with their claws and fangs, became the predators of the useless Eloi. The Traveller is shocked by the realization that, in a sense, the Morlocks were farming the Eloi as a source of meat. In this, the Traveller ruefully recognized an element of justice: “Man had been content to live in ease and delight upon the labours of his fellow-man, had taken Necessity as his watchword and excuse, and in the fullness of time Necessity had come home to him.”

The two species, according to the Traveller, evolved from “…the gradual widening of the present merely temporary and social difference between the Capitalist and the Labourer. … So, in the end, above ground you must have the Haves, pursuing pleasure and comfort and beauty, and below ground the Have-nots, the Workers getting continually adapted to the conditions of their labour. … Ages ago, thousands of generations ago, man had thrust his brother man out of the ease and the sunshine. And now that brother was coming back—changed!”

It is the harvest of elitism. Give one segment of the population a greater share of education, economic security, health care, and control over the media; give the other basically nothing but what they can scrap together, outsourcing their jobs to cheaper markets, stripping them of healthcare and access to education, and lock the doors against any attempt at social mobility. The elites will try to pretend that their livelihood does not rely upon the way things are, and write fine essays about the meaning of justice and importance of education. The others will turn to violence as the only means to break out of the structural inequalities holding them back. They will arm themselves, disrupt the government’s means for keeping order, and cheer for idiotic, brutish demagogues precisely because the elites hate them. In the contest of raw power, the elites will be at a disadvantage.

Wells wrote The Time Machine in protest against the class inequalities of his day, and as our own economic inequalities rapidly approach the severe levels of the Victorian age, the prescience of his parable is striking. But there is also a further differentiation of species (so to speak) taking place in our own world. It is the political divide between globalists and fascists. This cuts across the division between Haves and Have-nots, since globalists tend to be urban and spread across the economic spectrum, while the fascists tend to be suburban or rural and in the middle class or above. The political consequences of this divide are being seen across the world. To spin a similar tale around this division, a latter-day Wells would have to invent two new species – perhaps the Metros and the Qanons, or the Slushies and the Trumpos – with their telltale features and behaviors. It might make for another eye-popping morality lesson. But I worry that we won’t need a time machine in order to see it.