by Joseph Shieber

The traditional assumption in the United States has been that each person is individually responsible for their own health care. In other words, the US has a system in which the wealthy are able to afford more or better care (with the understanding that more care does not always lead to better health outcomes!), and the poor are able to afford less or no care.

There is something intuitively appealing about the idea that you should be rewarded in relation to the work that you’ve done or the results that you’ve achieved. It’s the basis of the well-known children’s fable, “The Little Red Hen”, in which the hen tries to get her fellow barnyard animals (dog, goose, etc.) to help her sow the seeds, reap the wheat, grind the grain, and bake the bread. Since none of the other animals are willing to help, when the bread is done the hen eats it all herself. In fact, the fable is so intuitively plausible that folksy free-market hero Ronald Reagan — pre-Presidency — used it himself.

The idea behind “The Little Red Hen” is so intuitively appealing that it’s not just limited to free market views. Even socialist thinkers from pre-Marxists like Ricardian socialists to later theorists like Lenin and Trotsky embraced the formula, “To each according to his works”, rather than Marx’s “To each according to his needs”.

Indeed, in a very useful paper, Luc Bovens and Adrien Lutz trace back the dual threads of “to each according to his works” and “to each according to his needs” to the New Testament. So, for example, in Romans 2:6, we see that God “will render to each one according to his works” (compare Matthew 16:27, 1 Corinthians 3:8).

In contrast, in Acts 4:35, we read that “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were owners of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold … and it was distributed to each as any had need” (compare Acts 2:45).

The deep textual roots of these two rival maxims suggests that each exerts a strong intuitive pull — though perhaps not equally strong to everyone.

Public health emergencies, however, reveal the fragility inherent in the motto of “to each according to his works” when it comes to health systems. Everyone’s health is interconnected, and that the ability of each individual to fight infection depends in part on everyone else’s having done their part.

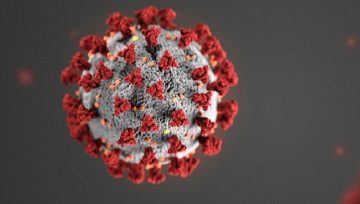

The most recent illustration of this comes from the threat of a pandemic of the newly-discovered COVID-19 virus. One of the effects of this threat is that it has led to strong questions about economic inequality and fairness of access to medical supplies and a potential vaccine.

For example, there was a widespread outcry when the current United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, refused to guarantee that a vaccine for the COVID-19 virus would be affordable for all. Those comments sparked renewed attention to Mr. Azar’s own troubling history with questionable pharmaceutical price increases.

In the ten years from 2007 until his nomination to the HHS position in 2017 in which Mr. Azar worked for the drug manufacturer Eli Lilly, that company recorded a three-fold increase in the price of insulin. This is despite the fact that insulin, which is necessary for diabetes sufferers to manage their condition, has not been substantially improved since its first medical use almost a century ago.

This outcry, while understandable, actually misses the deeper point about why Mr. Azar’s actions should concern us. Even if someone resists the moral pull of “to each according to his needs” in favor of the competing maxim “to each according to his works”, the application of that maxim in the case of public health emergencies can lead to catastrophe for all.

Public health experts note that two of the most important weapons in the fight against pandemics are early detection of those infected and widespread vaccination. The “to each according to his works” model of healthcare removes both of those weapons from our arsenal.

When Mr. Azar, who is himself a lawyer and has no medical or public health expertise, fails to guarantee that any COVID-19 vaccine will be widely available, he weakens the effectiveness of vaccines as a weapon against the spread of infection. Vaccines work best when they’re distributed widely among at-risk populations.

Mr. Azar’s comments, in other words, are an indication that the Administration fails to grasp that — unlike Presidential pardons, perhaps — public health crises do not discriminate on the basis of celebrity or outsize wealth. Rather, the health of each one of us depends on all of us doing our part.

The “to each according to his works” model also threatens the other weapon against pandemic, early detection. If only those who can afford to get tested for COVID-19 report themselves to authorities, then we won’t know how widespread the disease in fact is.

To take an extreme example of this, the Miami Herald recently reported on Osmel Martinez Azcue, who sought a test for COVID-19 after returning from a work trip to China and experiencing flu-like symptoms. Although Azcue was simply acting in the way recommended by the Centers for Disease Control to be in the best interests of public health, he now faces thousands of dollars of medical bills from his insurance company, the hospital where he sought testing for the virus, and the individual doctors who treated him.

Unfortunately, these troubling examples seem themselves to be systematic of wider trends that do not inspire confidence in the ability of the United States to deal with the growing threat of COVID-19.

Profit-seeking is already causing obstacles to efforts to combat the public health risk posed by COVID-19. Stockpiling and price-hikes are making it difficult for medical personnel to acquire the masks and protective gear they need to stop spreading infection further.

Although the United States has lost valuable time in planning for this impending health care crisis while it was still contained in China, it is not too late to take steps to blunt the impact of the infection. In order to do so, however, the Administration must appreciate that pandemics do not distinguish on the basis of immigration status, ethnicity, or income. To fight COVID-19 effectively, we must begin by appreciating that we’re all in this together.