by Thomas O’Dwyer

Is there anything more depressing than the happiness industry? Never mind Google, just check out Amazon Books for something to read about this mental snake-oil, and just look at that — “50,000 results for Happiness.” With so much advice available, it’s hard to grasp how there could be any misery left in the world. At the top of the list among the “happiness projects” and “happiness how-tos” sits The Art of Happiness by no less a global guru than His Holiness the Dalai Lama of Tibet. But wait; there’s less. The small print reveals that the Dalai Lama didn’t even write the book. It is a set of “observations and analysis” by some American psychoanalyst who “echos” the ideas of the world’s favourite holy man. I wonder if he’s happy with that.

The British feminist Lynne Segal has suggested that the “happiness agenda” ought to be named the “misery agenda”. She argues that it adapts people to the causes of their misery, rather than addressing them. That’s a nod to Professor Pangloss, of whom more later. The Dalai Lama is elsewhere reliably quoted as teaching that “the purpose of our lives is to be happy.” The American people’s genius, Benjamin Franklin, wrote that “wine is constant proof that God loves to see us happy.” Come on guys — this is a serious existential topic, and that’s all you’ve got?

The mystery of happiness, once owned by ancient high philosophy, is now all over the place. As with so much else in the disintegrated temples of ancient values, we can probably blame the Americans. The ancient wisdom of the Greeks, of Marcus Aurelius, the Buddha, Confucius and other giants has been deconstructed into streams of glib cliches that can be transformed into dollars by slapping them on mugs, T-shirts, Hallmark cards and blurbs for “self-help” trash. What have they wrought, those framers of the U.S. Constitution, by sticking into it that fuzzy inalienable right to “the pursuit of Happiness”?

Not happiness itself, mark you, as if a little happiness would be too much to ask. No, instead you can have the lifelong pursuit of happiness, alongside the pursuit of money, to bring joy to your life, and good luck with both of them. Of course, if you can’t catch actual happiness, you can always sell the illusion of it in small bottles from the back of a covered wagon, or later, on Amazon. As an aside, just ponder that word “inalienable.” It means something that cannot be bought, sold, or transferred from one person to another.

It’s about now that one should pose that question begging to be asked — exactly what is happiness? The cartoonist Charles Schulz said it’s a warm puppy. For John Lennon and Paul McCartney, “Happiness is a warm gun, yes it is (bang, bang, shoot, shoot).” Take your pick. Since the middle of the last century, happiness research has slithered out of theology and philosophy into a plethora of scientific disciplines — psychiatry, sociology, psychology, neuroscience, gerontology, medicine and even economics. The United Nations publishes an annual World Happiness Report — last year Finland was ranked as the happiest country in the world for the second year running. In 2008, the government of Bhutan enacted a constitutional amendment to install GNH (Gross National Happiness) as a government goal.

Since 2013, the UN has celebrated an annual International Day of Happiness to promote the importance of happiness in the lives of people around the world. In 2015, it launched a list of development goals, “aimed at ending poverty, reducing inequality, and protecting the planet – three key aspects that lead to well-being and happiness.” This is all very worthy and commendable of course, but so far our cynical fractured world has seemed more happy to ignore than embrace World Happiness Day. (It’s on March 20, if anybody cares.)

Because of its modern scientific drift, the term happiness is now associated with mental or emotional states, including positive emotions like contentment or joy. For personal happiness, choose from your thesaurus — delight, enjoyment, peace of mind, well-being, contentment, hopefulness, exhilaration, delectation, exuberance, contentment, flourishing. The multiplicity is unhelpful, but the word that probably introduced the concept in the west was eudaimonia. (In the early Pali language of Buddhism, it was sukha.) The Greek eudaimonia came from eu, meaning “well”, and daemon, a minor guardian deity. Eudaimonia implies a positive state of being that a person may strive toward under the protection of a benevolent spirit. This state of being was the best a person could hope for, so it has been translated as “happiness”, but like the translation of the Greek arete as virtue, the English misses the divine nature of the word that the Greeks would have understood to be implied. In other words, happiness was not just a contented state, but a blessed one, rendering its pursuit elusive and not altogether within human power to achieve.

But even in early Greek philosophy, eudaimonia would have no overt religious or supernatural significance. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics says that eudaimonia means “doing and living well.” The modern concept of happiness tends to lose this attribute of doing and living well. When we observe that someone is happy, we usually mean they are feeling pleasant because things are going well in their life. Eudaimonia was a more encompassing idea than feeling happy. The philosopher Zeno believed that happiness was not dependent upon present enjoyment and security, but also on an expectation that the good times would continue. This gave rise to the concept that no person can be judged happy before they are dead. While we are alive, something can go badly wrong, and goodbye happiness.

So, even as the concept of human happiness was forming, it was being hedged in with ah-buts and on-the-other-hands. For Zeno, it was “a good flow of life” that one expects to continue. Others suggested eudaimonia was living in balance with nature. The dour Stoics inevitably opted for a definition of eudaimonia which required a strong dose of virtue and discipline. Frederich Nietzsche was more impressed by the teaching of Epicurus that happiness was connected to one’s ability to remain cheerful during adversity, such as physical pain and ailments. (Nietzsche suffered from many illnesses.)

Epicurus died in 270 BCE, aged 72, and his emphasis on minimising harm and maximising the happiness of oneself and others has echoed down the centuries: “It is not possible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly, neither doing harm nor being harmed.” Epicurus, a startling materialist in an age of ubiquitous deities, attacked superstitions and beliefs in divine intervention. He believed pleasure is the greatest good, but the way to find pleasure was to live modestly, to be curious about the workings of nature, and to be aware of the limits of human desires. This was his path to tranquillity, freedom from fears, and absence of physical ailments. Epicureanism has been mistaken for hedonism but is more attuned to the later concepts of Buddhism in teaching that the absence of suffering is the greatest happiness. The Greek philosopher’s belief in enjoying the pleasures of a simple life in moderation could not be further from hedonism as we now understand it.

This emphasis on minimising harm and maximising happiness inspired the thinkers of the French Revolution, and others, like John Locke, who wrote that people had a right to “life, liberty, and property.” This mantra and the egalitarianism of Epicurus flowed on into the American freedom movement. The founding father, Thomas Jefferson, considered himself an Epicurean. This closes the circle leading from eudaimonia to “all men are created equal” and endowed with certain “inalienable rights,” such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Laurie Santos, a professor at Yale who runs classes on “psychology and the good life,” said in a recent interview on Huffington Post that rather than worrying about detailed definitions of happiness, people should lose some of their misconceptions on the topic. “One of the most common is that we can’t change our happiness,” she said. Research suggests genetics might affect happiness, but Santos said it only has a fraction of a role: “There is a genetic component to happiness, but it’s much smaller than we think. That means we really can take action to improve how we feel.” Another misconception is that happiness stems from our circumstances — how much money we make, where we live, what job we have, if we are in a relationship. External factors can affect our overall level of happiness, but except for extreme or abusive issues, they aren’t very influential.

“For those of us who are living above the poverty line in relatively safe situations, our circumstances don’t matter as much as we think,” Santos said. “This is a hard one to come to terms with, but working to change our salaries, jobs, and romantic relationships won’t affect our well-being as much as we assume.” Neither is happiness about being forever cheerful — feeling sad is actually a part of happiness. Research indicates that people experience a spectrum of emotions for a reason. We need to feel anger, sadness and grief when appropriate because it makes it easier to move through them and back to harmony.

That’s all very well but brings us not a whit closer to understanding the personal happiness thing we are urged to pursue. Quite the reverse, for it seems that purveyors of readymade happiness slogans and self-help books are relentlessly and ceaselessly pursuing us. They may get richer (which, as we know, does not bring happiness), but we get ripped-off, conned and confused (which may be a more of a recipe for some unhappiness). If we have a look at unhappiness by annoyance, it seems to ooze out of the marketing pitches of the snake-oil hucksters who seek to define our misery and then offer to cure it:

“Are you ignoring your dreams? Have you lost the courage to be yourself? Do you feel that your life lacks meaning and purpose? Do you find yourself avoiding the real issues in your life and focusing on the superficial? Are you overwhelmed? Do you procrastinate? Do you sometimes feel like you are your own worst enemy?”

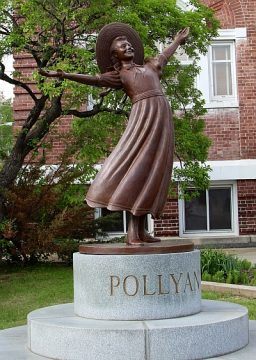

Well, who doesn’t say yes to each of those at some time or other — but these things come and go, and you are otherwise a reasonably happy person. Isn’t that good enough? “When you look for the bad, expecting it, you will get it,” says Pollyanna, the young girl in Eleanor H. Porter’s 1913 novel. Ah, Pollyanna. Now there’s someone who seems to take being happy under all circumstances so seriously that her name has become an adjective attached to thoroughly annoying optimism. Sentenced by her abusive aunt to miss dinner and instead eat bread and milk in the kitchen with the servants, Pollyanna thanks the aunt effusively for such a treat because she loves bread and milk and the servant girl Nancy.

“I never want to hear from any cheerful Pollyannas

who tell me fate supplies a mate;

that’s all bananas.”

(But Not For Me, by George and Ira Gershwin, sung by Judy Garland in the movie Girl Crazy.)

Forcing happiness-by-mating on young girls has been a form of abuse. There’s Cinderella, that poor sweet thing covered in ashes and every little girl’s favourite tale as she dreams of fairy godmothers, pumpkin coaches, palace balls, and the inevitable Prince I-am-so-Charming you can’t resist being happy ever after with me. Once upon a time, there was a little English girl named Diana, not poor but of modest means, who read the fairy talk and walked the fairy walk up the fabled aisle. Then Prince Charming reverted to frog mode, declared he would rather live as his mistress’ tampon than as Cindy’s husband. She suffered all the sexist indignities of the medieval lie, under the humiliating paparazzi gaze of a voyeuristic world. And she died unhappily for ever after.

Vinita Dawra Nangia, a columnist with the Times of India, recently compared her current state of happiness with that expressed in a column she wrote 20 years ago. In those younger days, happiness was all kittens and mittens:

“The drone of a bee on a summer day, the inflexion in a voice as it says my name; a baby’s dimpled bum; a sudden, unexpected smile; the curve of my man’s jawline … the twitter of birds; the softness of down; juicy, sun-kissed grass; the cool crispness of white sheets …” — OK, we got it, Vinita. And now?

“Twenty years on, happiness has mellowed and matured. I guess time and passing years do that to you. By the time you have had your share of all emotions — good and bad — and learnt to take them in your stride, you realise that come what may, life carries on … Happiness no longer takes you to heaven; grief does not permanently ground you. … And remember, the person who laughs too much, may not actually be the happiest!” She concludes that “comparing ourselves to others is the biggest mistake we make. The only way ahead is to get ahead of yourself – become better with each step. To me, guilt and regret are the toughest enemies of happiness.”

John Elder, a science writer on an Australian magazine, had another observation on the impact of time: “I have a terrific physician who has spent more than 40 years telling patients to cut down the booze, the meat pies and the cigarettes. He turns 70 soon. He plans to take all that good advice and flush it down the toilet. He’s looking forward to a last hurrah.” There’s a faint echo of Voltaire’s Candide there, although that adventurer’s last hurrah was more diminuendo: “Il faut cultiver notre jardin — we must cultivate our garden.”

Candide finally has his fill of the pathetic optimism of his old tutor Professor Pangloss with his Leibnitz-like mantra; “All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds.” Candide has witnessed and experienced the hardships and evils in the world, a path to slow and painful disillusion. He finally meets a Turk who has devoted his life only to simple work on a small piece of land and who ignores external affairs. This keeps him “free of three great evils: boredom, vice, and poverty.” Candide, at last, sees this a “commendable plan” for each person to exercise their own talents. This would be a happy life compared to the one of pain and misery he lived under the Panglossian idiocy that everything, however bad, was an adventure and for the best in the best of all worlds. So much for Pollyanna, Cinderella, Pangloss and, of course, Month Python’s Eric Idle, as the gang hangs on crosses at the end of The Life of Brian:

Always look on the bright side of life

For life is quite absurd,

And death’s the final word.

You must always face the curtain with a bow!

Forget about your sin – give the audience a grin,

Enjoy it, it’s the last chance anyhow!

So always look on the bright side of death

Just before you draw your terminal breath!