Sam Dresser in Aeon:

Sam Dresser in Aeon:

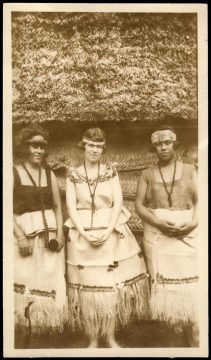

In 1978, after 50 years at the pinnacle of American opinion, the anthropologist Margaret Mead died with a secure reputation and a lustrous legacy. Her ascent seemed to mirror the societal ascent of American women. In some two dozen books and countless articles, she gave a forceful voice to a sturdy if cautious liberalism: resolutely antiracist, pro-choice; open to ‘new ways of thinking’ yet wary of premarital sex and hesitant about the Pill. The tensions in public opinion were hers, too. In her obituary, The New York Times called her ‘a national oracle’.

But posthumous reputation is a brittle thing. It’s difficult to defend oneself after death, and the years wear away a name, eventually reducing it to dust or mere ‘influence’. Issues change, standards shift, new thinkers rise: few names last forever. Within anthropology, Mead is still revered, but mostly as a way to understand the discipline’s origins. In the popular mind, Mead’s name has all but vanished, her reputation whittled down to an apocryphal quote found on coffee mugs and dorm-room posters: ‘Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.’

What’s more, Mead has become a target of vitriolic dislike for a particular kind of cultural conservatism.

More here.