by Adele A Wilby

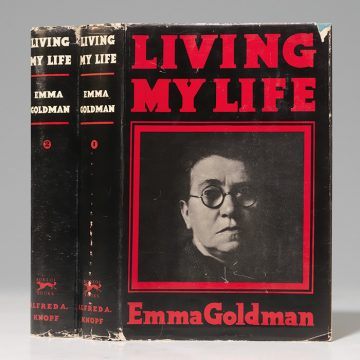

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

In a political era where many of the ‘isms’ in radical politics: Marxism, socialism, communism, anarchism, Trotskyism have either been discredited or have lost their appeal and force in western democracies, I found it refreshing to visit the life of one individual deeply involved in shaping those radical movements in the twentieth century: the anarchist, Emma Goldman, in her autobiography Living My Life.

The politics of ‘Red Emma’ as she came to be known, brought much controversy to Goldman over the course of her life: she was loved by many and equally hated and vilified for a politics that, in essence, aimed at, what she considered, would promote the well-being of humanity. ‘Anarchism,’ she wrote in her essay ‘Anarchism: What it Really Stands For’, ‘…stands for the liberation of the human mind from the dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government…for a social order based on free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth…anarchism is the philosophy of the sovereignty of the individual’. Great ideals! However, conceptualising ‘anarchism’ in such terms suggests a tension between collective interest and well-being, and the individual, a tension not fully resolved in her writing. But as Goldman was to realise over the course of five decades of political activism, the zeal behind her political ideals often resulted in the corruption of those good intentions and were the source of disappointment and nefarious practices, as exemplified in a kindred ideology, ‘socialism’, during Russia in the early twentieth century.

Nevertheless, despite the idealism within the political philosophy of anarchism, Goldman and other thinkers like her, such as her mentor Peter Kropotkin, and her life-long colleague and friend, Alexander Berkman, left a political legacy that is worthy of critical attention.

My purpose here however, is not to debate the credibility of her anarchist politics; that is a perennial debate in political philosophy, but rather to examine the life that Goldman lived in the pursuit of her political objectives: her life is an excellent example of how the commitment to radical politics unfolds in unforeseen ways to impact on the individual, challenge their commitment, pose a threat to their very existence, and ultimately to create the extra-ordinary person that was Emma Goldman. There was no armchair politics for Goldman; her life and politics were one and the same. However, living an all-consuming radical politics that ultimately sent her to prison, saw her deported from the US, and put her life on the line in the way that Goldman did, is a commitment to political principles of a different order.

Goldman’s autobiography reflects an unfolding of the deepening gravity and implications of her radical politics on her life: the more deeply the demands and challenges of her activism, the more serious the tone in her autobiography. Thus, in the first volume we see the transformation of an innocent young Lithuanian Jewish immigrant to the US into an intellectually powerful, articulate exponent of radical politics. So too, over the course of her two volumes do we see the transition from idealism to the practical realities that radical politics entails. In volume two, a sense of disappointment creeps into her autobiography as she comes to terms with the reality of political practice. But how did Goldman get to the politics of anarchism, and to live the extra-ordinary life she did for five decades?

Goldman was born into an unremarkable Jewish Russian family, but ironically it was that family context: discord between parents and siblings; the sense of stifling suffocation of family contexts, and an impulse to get out of the situation, that pushed her out of home and set her on a path for her to become the person she did. But once out of the family context, not infrequently also there is a ‘trigger’ that sets in motion an awakening to the reality that pastures are indeed greener in some instances; there is more to life than what is socially defined or expected. In Goldman’s case the ‘awakening’ occurred as a result of a chain of events once in the US that took her to a meeting with Johann Most, a fire-band speaker derided by the press for his denunciation of the conditions of the working people in America. With one political event and the meeting of one personality leading to another, coupled with her own experience and outrage at the oppressive and exploitive conditions of the factory workers in nineteenth century capitalist America, anarchist politics became, for Goldman, a possible solution to the social injustice, oppression and exploitation that characterised the life of working people in the US at the turn of the nineteenth century.

But apart from the objective conditions of her wider politics, how did Emma fair as young woman amongst all those ‘radical’ men involved in anarchism and other ‘isms’ during this period of American left wing history. Ultimately it is really at the personal level that women learn just how ‘radical’ is the partner with whom she is involved, and so it was with her relationship with one of her earlier lovers, the anarchist leader, Johann Most. Most, she knew, hoped for a ‘settled’ family life, and Goldman was faced with that choice that many women then, and to some extent to this day, wrestle with; a choice between family life and a career, or indeed, in Goldman’s case, of political activism that guaranteed a less ‘settled’ life. Although the idea of motherhood appealed to her, niggling away in her thoughts was the politics of the day, and indeed the man who was to become her most reliable and trustworthy radical companion in the politics of anarchism: Alexander Berkman. We can see Goldman’s dilemma on this issue of choice between a family life and political engagement when she says: ‘…How wonderful it would be to have a child by this unique personality (Johann Most)! I sat lost in thought. But soon something more insistent awakened in my brain – Sasha (Alexander Berkman), the life and work we had together. Would I give it all up? No, no, that was impossible, that would never be!’

Goldman never went on to be a mother but she was most certainly a woman of great emotional breadth and she loved deeply and widely. Indeed, as we learn throughout her autobiography, one of the defining characteristics of Goldman’s personality was her compassion for others, manifest so explicitly in her struggle to improve prisoners’ rights and her sharing of resources and caring for fellow inmates during her periods of imprisonment.

However, any politics that involves idealism must, inevitably, confront the reality of what is politically possible. Crucial to any transformation of society is that the subjective conditions for radical social change must be parallel with the objective conditions; the people for whom radicals struggle must also share the political vision being proposed as an alternative structure of society, if radical politics is to stand any chance of success.

Although there were pockets of interest in the US on the issues for which Goldman and her colleagues struggled, the support was not on a level to effect revolutionary social and economic transformation. This became apparent early on her political activism when the workers failed to rally to the support of Berkman when he was sentenced to life imprisonment following an attempt to kill the factory owner Fiske, despite the exploitation of the workers for which Fiske was known. Arguably the workers’ response was the beginning of the grounding of radical politics for Goldman, a process that ultimately culminated in disappointment with the reality of ‘socialist’ politics when she witnessed the level of oppression of intellectuals and other dissident voices by the Bolsheviks during her short stay in the Soviet Union following her deportation in 1919. In that sense also, any radical politics in any society where there is a real challenge to the status quo, invariably brings those involved in such politics to the attention of the state authorities; state informants infiltrate all level of radial political engagement, be it personal or on a collective level, which ends with individuals such as Goldman and Berkman being brought to the attention of the state authorities. What follows is the mobilisation of all the state power to ensure that any radical politics or persons are either contained, or crushed by one means of another. In the case of Goldman, the state mobilised its apparatuses to contain, and hence to crush the ideals and individuals involved in anarchist politics. Goldman endured terms of cruel imprisonment and indeed threats to her life by ‘vigilante’ activity throughout the course of her political life. It is to her, and indeed Berkman’s credit, that they endured and survived the physical and psychological hardships of prison life imposed on them by the state authorities. However, as Goldman was to learn, despite her innocence in many incidents to which she was alleged to have been involved, and the humanity that drove her politics, she could not escape the watchful eye of the authorities of the state which were determined to crush her voice and what she stood for. Ultimately, the state justified her expulsion from the US back to Russia, along with her enduring friend and staunch and strong political colleague, Alexander Berkman.

While the deportation of Goldman from the US was a wrench from friends and from the place where she had invested so much of her life and political energy, she departed with an expectation that she was returning to her ‘new’ old country, Russia, where social revolution had at last come to fruition. Alas, however, as she was to realise once again, idealism is one thing, the political reality of implementing an ideology can be quite something else; not all accept or are prepared for the implementation of policy process that brings about fundamental change in the system, and handling opposition to such far reaching social transformation is a crucial test of the real nature of the radical politics at play. Indeed, in a system based on the principle of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, the Russian revolution, as Goldman came to realise, was less about the proletariat and more about dictatorship, as disillusionment with the Bolsheviks soon set in; the intelligentsia and dissenters of the system were being banished to dark prisons and political executions of those who questioned the strategy, policy and hegemony of the Communist Party were frequent; the agriculture sector was bled to feed the city population, and priority was given to heavy industrial development; the conditions of working people for whom the ‘revolution’ was intended were often arduous, and the people lived under a regime of fear, an anathema to Goldman’s politics of liberty, social justice and equality that she had struggled for over the decades.

But it is not only the implementation of policy that is significant in any radical political context; it is the individuals behind such policies that are important, since it is their thoughts that foment the rallying cry from which policy develops, and leads to implementation. Thus, while Goldman and Berkman saw the ‘revolution’ in Russia as part of an overall global struggle of the workers, Lenin rejected their anarchism and viewed such issues as free speech as ‘a bourgeois prejudice’. Significantly also it was clear in their meeting with Lenin, that Goldman and Berkman were viewed as minor players in the grand scheme of Lenin’s radical strategy for Russia. Likewise, Trotsky’s reputation was bigger than reality, and this became evident when he sanctioned the crushing of a rebellion against the Bolshevik government by sailors at the Kronstadt naval base who were demanding the right to choose their own representatives. Trotsky’s action against the sailors who had been staunch supporters of the Russian ‘revolution’, were the last straw for Goldman and Berkman, and with that they resolved to leave Russia as quickly as was possible while it was safe for them to do so, and they found their way back to Europe and, for Goldman, ultimately to Canada.

Goldman lived an interesting life after her return to the west, but one is left with the impression that the time of her deportation to Russia marked a turning point in her political life. For sure, she never really had the influence and richness of political engagement that she did during her years as an activist in the US. Nevertheless, she remained true to her fundamental political principles of the importance of liberty, social justice and people’s political rights, and this is apparent in the way she campaigned to highlight the events happening in Russia and for the interests of prisoners there. Clearly, in doing so she set herself, and anarchism, apart from the ‘revolution’ that was taking place in Russia.

Despite the lapse of time since her demise in Canada in 1949, Goldman’s life story evokes memories of a gone-by era, of a time when politics fuelled by an optimism that social change was indeed possible, if not around the corner, and that life could be better for everyone, and not just the few. Such idealism drove the political commitment and passion for revolutionary change in Russia in the early twentieth century, but also the politics of many individuals in western democracies in the latter part of the nineteenth century up to, although to a lesser extent, nearing the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. Throughout that phase of social upheaval many radical thinkers and activists came and went, and few have left a lasting legacy as did Emma Goldman. She belongs to a past, which was, given the politics of today in the US, UK and Europe, arguably an era of lost opportunity. Nevertheless, Goldman was a prolific writer, particularly of letters, which are thought to run into quarter of a million, apart from her theoretical comments, and they are testimony to the radical politics she espoused. That apart, it was the realisation of her politics in the way she lived her life that also leaves a lasting legacy: she was indeed a rare phenomenon: a thoroughly radical and decent human being prepared to sacrifice her life for political principles she considered would further the progress of humanity, and the liberty of the individual.