by Michael Klenk

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

I live and work in two different cities; on the commute, I continuously ask my phone for advice: When’s the next train? Must I take the bus, or can I afford to walk and still make the day’s first meeting? I let my phone direct me to places to eat and things to see, and I’ll admit that for almost any question, my first impulse is to ask the internet for advice.

My deference to machines puts me in good company. Professionals concerned with mightily important questions are doing it, too, when they listen to machines to determine who is likely to have cancer, pay back their loan, or return to prison. That’s all good insofar as we need to settle clearly defined, factual questions that have computable answers.

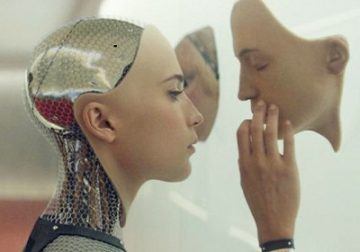

Imagine now a wondrous new app. One that tells you whether it is permissible to lie to a friend about their looks, to take the plane in times of global warming, or whether you ought to donate to humanitarian causes and be a vegetarian. An artificial moral advisor to guide you through the moral maze of daily life. With the push of a button, you will competently settle your ethical questions; if many listen to the app, we might well be on our way to a better society.

Concrete efforts to create such artificial moral advisors are already underway. Some scholars herald artificial moral advisors as vast improvements over morally frail humans, as presenting the best opportunity for avoiding the extinction of human life from our own hands. They demand that we should take listen to machines for ethical advice. But should we?

It is vital to take proposals for artificial moral advice seriously because there is a real need for improving our moral judgements. Not only are our actions often morally amiss, but empirical research has documented several striking problems with ethical decision making itself. For example, humans routinely favour members of their own group over outsiders, and most ethicists hold that this preference cannot be ethically defended. Racial bias is morally illegitimate, too, but it implicitly influences even people who explicitly affirm egalitarian principles. Similarly, situational factors, such as whether you are in a good mood, hot or cold, tired or awake, disgusted or not, have been shown to sway peoples’ moral judgements. That is disturbing. Our moral beliefs should be sensitive only to things that ethically matter, and ethicists are hard-pressed to explain why such situational factors should affect moral judgements. This makes it essential to consider the prospects of artificial moral advisors seriously.

The prospects of artificial moral advisors depend on two core questions: Should we take ethical advice from anyone anyway? And, if so, are machines any good at morality (or, at least, better than us, so that it makes sense that we listen to them)? I will only briefly be concerned with the first question and then turn to the second question at length. We will see that we have to overcome several technical and practical barriers before we can reasonably take artificial moral advice.

To begin with, there is a fundamental issue with taking moral advice from anyone that we have to keep in mind when assessing the prospects of artificial moral advisors. When we have factual questions about the weather, the solution to an equation, the departure time of a train, and so on, we can rely on testimony and gain knowledge. We just need to seek out someone who has reliable information on the topic, indicated by an excellent track record, and then we can happily rely on the information provided. In fact, large parts of our individual knowledge are based on testimony – by teachers, scientists, politicians, and our peers. That is also why it makes sense to take advice from a machine when it comes to directions, descriptive information about restaurants, or computationally complex predictions.

However, many philosophers suspect that moral testimony works differently to non-moral testimony. An important reason is that moral knowledge seems to require the ability to give good reasons for one’s conviction. For example, if you know that eating meat is morally wrong, then you will be able to explain why it harms the animal, how animals are sentient, and why we ought to limit harming sentient beings, amongst other things. You won’t get that kind of insight and information from just taking someone’s word that ‘eating meat is wrong.’ That is one reason to doubt that moral testimony gives you knowledge.

In contrast, if a routine commuter, or a trustworthy app, tells you that the next train leaves in 30 minutes, then that’s all you need to know. So, when we look for artificial ethical advice, we should first ask what moral knowledge requires and why we form moral beliefs in the first place. Perhaps what we are looking for in morality is not just truth, but understanding – and that cannot easily be transmitted by testimony.

To illustrate, it helps to compare the situation to studying chess with a computer programme. Every chess novice can take the advice of the application, executing brilliant moves. But that seems not very helpful if the student is not able to understand and explain why that move makes sense (apart from the superficial reason that it is the best move available since it was recommended by the chess computer). If learning about morality works similarly, then getting snippets of information from our potential artificial moral advisors will not be enough to gain moral knowledge. The prospects of artificial ethical advice might then be nipped in the bud. The point here is thus that our moral advisor’s ethical proficiency does not settle questions about what we, the people being advised, ought to believe.

With these questions about how to reasonably form moral beliefs in mind, we can now tackle the second core question about artificial ethical advisors: Are machines any good at morality? There are several ways in which they can give us ethical advice; none, however, is currently without problems.

Consider first what we can call ethically aligned artificial advisors. These machines can tell us what to believe based on ethical principles and values that we provide them with. Suppose, for example, that you are a vegetarian looking for a meal. Mobile mapping services could offer an option to search for vegetarian restaurants. For example, The Humane Eating Project already provides a mobile app that allows searching for “Humane options (vegan, vegetarian, and humanely-raised).” This is a form of ethically aligned artificial advisory. The machine helps those who want to promote ‘vegetarianism’ as a moral value. The value is already set by the designers of the app. Furthermore, the machine works with what might be called an operationalisation the value vegetarianism. For example, vegetarianism might be defined as the availability of meat-free meals in the restaurant (though other operationalisations would be possible, as we will see below).

Ethically aligned artificial advisors seem to aid our moral decision making. That is because making the right moral decisions often requires assessing non-moral information accurately to check whether a given moral value applies. Consider ‘humanely-raised’ meat as a value. Apart from asking whether this is a value, you need to be a good information processor. Where does the produce come from? What are the working conditions in that restaurant? Machines are good at information processing. Given clearly operationalised moral values, this form of artificial moral advice could be implemented.

However, ethically aligned artificial advisors have significant limitations. First, they are somewhat superficial. Discovering the correct moral principles and values is the tough part of moral decision making. That part would still have to be done by humans. For example, above, we presupposed that ‘vegetarianism’ or ‘humanely-raised’ are values. But are they? Ethically aligned artificial advisors rely entirely on us to answer these questions. So, in a top-down approach to providing artificial moral advisors with moral input, we rely on our own frail and disputed moral judgements. This is what we wanted to avoid.

Moreover, operationalising moral values or principles is a task in ethical decision making par excellence. Consider ‘vegetarian’ again. Should we operationalise it as ‘meat-free meals available,’ as ‘meat-free restaurants,’ or even as ‘no animal harmed in the production of the meal?’ Any ethically aligned artificial advisor must have an answer to these questions. Again, however, since ethically aligned advisors cannot come up with their own operationalisations, it will have to be on us to provide answers.

The limitation of ethically aligned artificial advisors raises an urgent practical problem, too. From a practical perspective, decisions about values and their operationalisation are taken by the machine’s designers. Taking their advice means buying into preconfigured ethical settings. These settings might not agree with you, and they might be opaque so that you have no way of finding out how specific values have been operationalised. This would require accepting the preconfigured values on blind trust. The problem already exists in machines that give non-moral advice, such as mapping services. For example, when you ask your phone for the way to the closest train station, the device will have to rely on various assumptions about what path you can permissibly take and it may also consider commercial interests of the service provider. However, we should want the correct moral answer, not what the designers of such technologies take that to be.

We might overcome these practical limitations by letting users input their own values and decide about their operationalisation themselves. For example, the device might ask users a series of questions to determine their ethical views and also require them to operationalise each ethical preference precisely. A vegetarian might, for instance, have to decide whether she understands ‘vegetarianism’ to encompass ‘meat-free meals’ or ‘meat-free restaurants.’ Doing so would give us personalised moral advisors that could help us live more consistently by our own ethical rules.

However, it would then be unclear how specifying our individual values, and their operationalisation improves our moral decision making instead of merely helping individuals to satisfy their preferences more consistently. Mere personal preferences should not be all we care about, lest we forget why we were looking for artificial moral advise in the first place. The entire project of seeking to improve our ethical decision making presupposes that there is more to morality than mere preferences – there is supposed to be moral truth.

Therefore, ethically aligned moral advisors alone won’t fulfil the machine ethicist’s wild dreams of moral progress. We need to take it one step further. To fully benefit from artificial ethical advice, we need morals ex Machina: insight into the realm of moral values provided to us by machines. If machines were able to discover moral truth on their own, they would be ethically insightful artificial advisors (of course, this requires that there is moral truth. But the entire idea of ethical advice depends on this assumption, so let us take it for granted.)

How could such an ethically insightful artificial advisor work? Above, we have seen the limits of using a top-down approach to moral advice (where, you will recall, we humans provide the moral principles that machines apply). A more promising route to morals ex Machina goes via a bottom-up approach: Machine learning. An ethically insightful artificial advisor would aim to extract moral principles and values from learning data gathered from historical texts, survey responses, and eventually, observations of actions. We could learn these principles and values and ultimately make better moral judgements.

To reasonably trust the output of the ethically insightful advisor, we must assume that moral truth is somehow reflected, explicitly or implicitly, in the artefacts of human behaviour that can be used as training data. What humanity has done or said would contain kernels of the moral truth, and the machine would just have to figure it out. Several variations of the learning procedure are possible, depending on what kind of data is taken into account. For example, training the machine could use historical information or current responses.

The problem with that assumption, however, is that our moral track record is notoriously bad. After all, that is why we are looking for artificial moral advisors in the first place. As any computer scientist will tell you if you put garbage into a computer system, you get garbage out. There was a lot of garbage in our human moral history: Humans have found it acceptable to enslave their fellow human beings, to cheat and deceive for personal gain, to mistreat women, to annihilate entire people. It seems absurd to demand that our future moral advisors should learn from such bad examples.

Moreover, even if we might hope that the mistakes of individuals and even groups are washed out in the aggregate (perhaps history indeed shows a noticeable trend to ‘enlightenment values’), there is still a question about which types of data to select to train our ethically insightful artificial advisors. People are morally lazy – their actions do not align with their moral judgements. That suggests that we should focus on moral judgements rather than actions as appropriate training data for ethically insightful artificial advisors. After all, it might be more likely that people honestly judge that deceiving is wrong, while they succumb to prudential, egoistical desires in their behaviour. Judgements would then be more reflective of moral truth. But where do we get enough training data from? And whose moral opinions should we analyse? Lest we are confident in our data source, there is a danger that the garbage-in/garbage-out problem arises anew.

Perhaps our best shot would be to start training the machine with the carefully considered ethical opinions of ethics professors, plus the entire canon of academic moral philosophy (I would say that as a moral philosopher, wouldn’t I)? At least, one might think, these opinions have carefully been evaluated, and perhaps that increases their chances of being on track. Some of the principles that the machine will come up with from analysing this data should be known to us already (which can serve as a confirmation that the device is on track). Furthermore, we might hope that machines discover, in that big haystack of human moral opinion, hitherto undiscovered ethical principles. That would seem to realise the aspirations of morals ex Machina.

However, when our ethically insightful artificial advisor presents us with such novel principles, which, at first sight, seems like a good thing, we only face two further problems. First, novel principles raise problems about whether we would be able to understand them, and whether the machine could explain how it arrived at them (which might be required in light of the earlier discussion about the limits of moral testimony). Second, deciding whether to adopt the machine’s novel ethical principles puts us in a dilemma. Either we can assess the reliability of these new principles, or we cannot. If we can, then we have access to the moral truth ourselves, but then we do not need the machine’s moral advice. If we cannot, then we would need its help, but then we have no access to the moral truth and therefore cannot evaluate whether we should trust the machine. Either way, there seems to be no job for ethically insightful machine advisors to do.

Because of these problems, it seems that our aspiring artificial moral advisors are letting us down – they just don’t have good enough credentials for us to rely reasonably on them to discover moral truth. Practically, we might, of course, insist on using artificial moral advisors just because it makes us feel good or because it meets our needs. That would not be surprising. Consultants and designers, for example, also rely on little more than the fact that past clients were satisfied to justify their expert status. But we should apply stricter standards in the moral case, and be sure that the advisor is doing well on us before entrusting them with our moral outlook.

We should, therefore, wave goodbye to premature hopes for using machines to gain access to moral truth and knowledge directly. Nonetheless, there might be a more limited role to play for machines. They could take care of our internal moral economy by alerting us of inconsistencies in our moral thinking, thereby limiting our chances of making moral mistakes in our thinking. All else being equal, a set of consistent moral beliefs is better than a collection of contradictory ideas, at least if one thinks that there is moral truth to be discovered.

Accordingly, we could make use of artificial moral consistency checkers. Your individual moral consistency checker could make an inventory of your ethical commitments and then inform you about any conflicts. For example, you might believe that you ought not to hurt sentient beings (A). And you might also think that it is permissible to eat meat (B). Suppose you also have a background belief that animals are sentient beings. Clearly, that is an inconsistent belief set: You cannot consistently maintain A and B, in light of your background beliefs. The artificial consistency checker could notify you of this fact, which might lead you to revise your moral beliefs, thereby improving your internal moral economy.

Though the artificial moral consistency checker would be limited in application (it will show us where inconsistencies arise, but it will not tell us which belief to give up), it represents the most reasonable use of artificial moral advisors at the moment. We will make the final call on which views to keep, and which ones to give up, and this is a good thing because we will retain the autonomy to form our own opinion.

It is time to draw a conclusion. Both ethically aligned and ethically informed artificial advisors are a long shot away from expertise on morality. We either have to supply them with our own moral principles, which is of limited use insofar as our own moral judgements might be flawed, or we must entrust them with discovering moral truth themselves which is problematic because we have scant reason to believe that they are better than us at finding out about the moral truth. At best, we should make use of artificial consistency checkers, which can help us increase our internal moral economy while leaving open what we ought to think.

In many ways, then, we have reason to stick to the wetware way of making moral decisions for some time to come. We should not forget, however, that artificial moral advisors might be indirectly helpful. The process of trying to create an artificial advisor might teach us something about our morality when we need to get crystal clear about our moral principles. Moreover, their output, even if flawed, might prompt us to think seriously about it, which might then lead to understanding and knowledge. Morals ex Machina this isn’t, but an improvement it may well be.