Anton Jägerat nonsite:

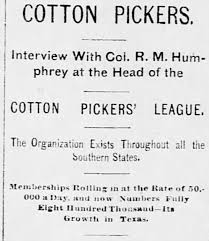

It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s.

It has not always been the case, after all, that American academics saw populism in terms of “identity.” In the 1920s, American historians could still look back fondly on the Populist episode as one of the many episodes in the age-long American class struggle. To followers of Charles A. Beard, doyen of the Progressive School in American History, Populism represented the last revolt of the small freeholding class, who, while being crushed by the advent of the industrial society, protested their new market-dependency by uniting on class lines. Other writers in this tradition, such as Vernon Parrington or John Hicks, shared their sentiments. Parrington’s Main Currents of American Thought (1927) cast “populism” as the revolt of small property-holders upholding the Jeffersonian ideal, sharing a pedigree which went back to the Founders’ Age. John Hicks’ classic The Populist Revolt (1931) tracked a similar genealogy, trying to show how the aims of the original Populist movement were translated into the working-class agitation of the incipient New Deal. Another classic of Populist historiography, Comer Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1937), made a similar diagnosis of the economic character of the “agrarian crusade” which took Southern states by storm in the 1880s and 1890s.

more here.