by Cathy Chua

In that famous speech where Leonard Cohen told us ‘…never to lament casually’, he continued ‘And if one is to express the great inevitable defeat that awaits us all, it must be done within the strict confines of dignity and beauty.’

When I’m in Geneva I often go to the large flea market in Plainpalais. For most people it’s a source of bargains, or a way to pass the time. But I see death everywhere there, with no lamenting and a marked lack of respect. I am a mourning party of one. I see people’s lives laid out for a few francs. What’s there often tells a story. Curated collections of jazz music, or slightly kooky egg cups from everywhere. From the lost days of photographs, albums of happy tourist are muddled with strange books to see in this market, but put in place by the pictures. I even see home sometimes, a story of Indigenous people, or a guide to Australia, snapshots amongst them.

I lament not only the person who has gone, but the process which ends here, in a scrabble for a bargain. Did nobody care about this deceased human being, that their belongings have been tossed into cardboard boxes to be disposed of in indecent haste? Did the person who left behind this collection of sewing bits and bobs have no one to sew for? I spend a lot of time imagining what had existed. I am moved to buy things I shouldn’t. Does nobody want this framed picture of a child from the turn of the nineteenth century? Somebody must. I must.

But I mainly don’t. I can’t single-handedly save the small histories of these human lives. Instead I mostly stick to a reserved regret and try to honour what I see when it tells a story.

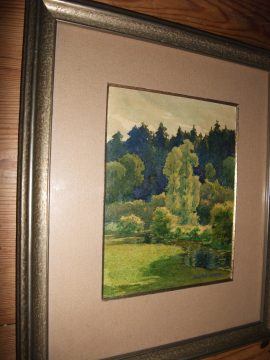

Sometimes the story only appears after I get home. On a recent visit I returned with a small picture which cost about $US20. It wasn’t attached to a history that I was able to read, it wasn’t obviously part of a story. I bought it because it was a green landscape, the green that is conspicuously missing from my urban Genevan surrounds. Unlike a lot of my flea market purchases, this one has a legible signature. André Engel. A wiki entry tells me that he was born in 1880, his first lessons were with Hans Sandreuter and his teachers subsequently included Vignal and Merson. Although the company he kept included minor local notable painters such as Maurice Achener, one could certainly not afford Engel that status, ‘minor’. Look hard and you can spot a couple of his pictures online. Fortunately I’m not in the flea market art hunt for the money. For me, being a historian, means I see that a life adds value and meaning to a picture, just as it might to a person’s writing work. Now that I’ve delved into the story behind this picture, it makes me like it more. I see nuance, colour, texture that wasn’t there before. It’s like a painting growing as it is watched.

André Engel is of the eminent family, the Engels, who owned the DCM textile factories in Mulhouse. I say ‘eminent’ not because this business afforded the family great wealth, though it did – their family house was and still is the Château de Ripaille – but because he is the grandson of Frédéric Engel-Dollfus, a philanthropic socialist industrialist of a type long gone. I can’t imagine anything being more the opposite of American Objectivism than Engel-Dollfus’s Saint-Simonist bent. To quote him:

‘the boss owes more to the worker than his salary … ‘ and ‘It is his duty to take care of the moral and physical condition of his workers, and this obligation, a moral one which no kind of salary can replace, must prevail over particular interests.’

These were not objectives for him, they were imperatives and his impact must have been profound. A summary of Jérome Blanc’s research into Frédéric Engel-Dollfus’s works can be found here. It includes:

- Emergency and retirement funds, schools and asylum rooms (ancestors of nursery schools ) for DMC staff.

- Collective insurances allowing the workers to secure their furniture on extremely advantageous conditions, created in 1865

- The Asylum of vigils and disabled workers, created in 1851*

- Until 1883, he welcomed 145 boarders and paid 1,166 boarding house pensions.*

- Significant measures to protect the public health of the area.

- The “Association for Preventing Accidents of Machines” (1867-1896), which he directed from 1867 to 1883, one of his obligations to workers. At the Universal Exhibition of Paris of 1878, he displayed inventions for making workers’ processes safer and was awarded the gold medal of the Jury.

- The “Dispensaire for sick children” (founded in November 1883) In 1921 the heirs of Julie Engel-Dollfus offered it free of charge to the commune. It operated until 1960 and treated more than 78,000 children until 1921.

- Bounteous purchase of artwork for museums including Rembrant, Rubens, van Dyck etc, also antiquities of the Roman and other periods. They can still be seen today in the Museum of Fine Art Mulhouse.

*trans by Google from the French, and it is unclear to me what exactly this entails.

As may be evident from the last point, he had an artistic sensibility. Indeed, Monsieur Blanc states that when he was young it might more have been expected that he became a musician than an industrialist. André was three when his grandfather died, but the influence no doubt lived on right through the twentieth century. It was André’s daughter Elizabeth Engel-Necker, for example, who created the Foundation that exists today supporting the Chateau and its surrounding environment. And most notably, the family’s woodlands are the site of The Memorial to the Righteous. ‘The Ripaille estate’s 130 hectares were chosen for the monument as the estate is an important historical centre for the Haute-Savoie and a symbol of resistance, spirituality and solidarity.’

Engel himself became a qualified doctor and although he stopped practising very early, he nonetheless served in WW1 in a medical capacity: he operated the first radiologist ambulance. That fits in with his early experience after becoming a doctor. He ‘experimented with chemistry’, according to his wiki page, and helped create the radiography department of Lausanne hospital. However, by 1905 he was devoted to painting. Despite this dedication, and the travel he did, he nonetheless had another side. A review appeared in a local daily newspaper in 1944 of his work on trees.

In the early 1930s, André established a forest arboretum to experiment with how various types of trees might suit the climate of the area. A local website says that ‘Here you will discover the old oak grove (53 hectares), the arboretum sylvetum André Engel (19 hectares) and the National Memorial of the Righteous of France. By an agreement between the family owner of the estate and the town of Thonon, which owns a section of these woods, the arboretum and the forest are open to the public following specific routes from the forest house.’

Showing the artistic sensibility that ran through the generations, much later, a descendant commented that André’s father, Frederic, ‘…was an enlightened art collector with a collection of European importance. And he was a man of his time: for Ripaille, he wanted to create a “total work of art”, in the spirit of Wagner’s operas. From bathroom taps to gardens, Engel-Gros wants a complete harmony, giving great importance to the relationship between buildings and landscapes.’ And then in the son we see the landscape paintings and the arboretum. Above all we might now see this arboretum as André Engel’s message for the future, our present. His point was to investigate the ‘rational reforestation of our countries.’ It was a serious work, completed after Engel’s death by Professor Cosandey then Professor of Botany at Lausanne University.

Now I look again at this small, simple picture of green and you can see why it has become layered and nuanced for me. It may not be infinity in a grain of sand, but it is a lot of history, care and sentiment bundled up into its unimposing frame. And to come back to Cohen, this backstory has added dignity and beauty to how I view it.

Postscript: living in French parts makes me aware of how much of interest, historically, is unknown to English speakers because it isn’t available in English. Not surprisingly, more than one book has been written about this family. But the books, the wiki entries and family history pages are available only in French that I’ve been able to discover. So, I give a few links here for more on the story of the painter Engel and his family, in French. It isn’t the happiest language for Google translate, but you can pick up the gist of the story. Please explore. And keep trees in mind and a family at the top of industry who thought their workers mattered. There are messages for today’s world to be found here.

An account of The Memorial to the Righteous and why it is in the Engel family property is here.

Jérome Blanc is a professional geneologist who wrote a book about the family, going back hundreds of years. You can read a short summary here. For a family tree, start here and here, and here. It is worth noting that Jean Dollus, father-in-law of André’s grandfather had similar attitudes in terms of the relationship an industrialist should have with his workers, no doubt a source of inspiration.

The death notice of Engel in Nouvelliste Valaisan Mardi 5 Mai 1942 is here.

Review of his essay/report on trees Nouvelliste Valaisan Dimanche 27 fevriér 1944 is here.

For more on Frederic Engel-Dollfus go here and the wiki page for Jean Dollfus, his father-in-law is here.

View a couple of his landscape pictures here.

He can be found described as a chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, as were others of his family – there is, however, no complete list of these available and although there is no reason to disbelieve it, nor can I confirm it.