by Joseph Shieber

In the most recent case of a white person’s discomfort resulting in the ejection of African Americans from public spaces, a young, black couple who were picnicking with their dog at a KOA campground in Mississippi were threatened at gunpoint by a white campground manager and forced to leave.

This sort of case calls to mind one of the hottest topics in the the theory of knowledge at present (and one of the topics of the 22nd lecture of my “Theories of Knowledge”). It’s what philosophers call “moral encroachment” and involves the claim that the amount of evidence you need in order to have sufficient support for believing something depends in part on the moral implications of that belief.

All of this can seem really abstract. However, if you take it step-by-step, you can see that the ideas behind the notion of moral encroachment are pretty easy to grasp.

First, if we’re going to recognize the idea of moral encroachment, then that means recognizing that beliefs can have moral implications at all. And that can seem difficult to accept.

What it would mean to say that a belief has moral implications is this. It’s the idea that, over and above being able to weigh a belief as being supported or unsupported by the evidence, we can also evaluate at least certain beliefs based on their moral qualities.

This explanation helps to demonstrate where the term “moral encroachment” comes from. The idea is that moral considerations — the considerations arising from a belief’s moral qualities — can encroach on what we might call “epistemic” considerations — those having to do with whether a belief is supported or unsupported by the evidence.

Before we assess the evidence for the thesis of moral encroachment, though, it will help to see if it even makes sense to suggest that any beliefs can have moral implications at all.

Here’s an example intended to support the idea that beliefs can be evaluated based on their moral qualities. As far as I am aware, it was first discussed by the philosopher Tamar Gendler.

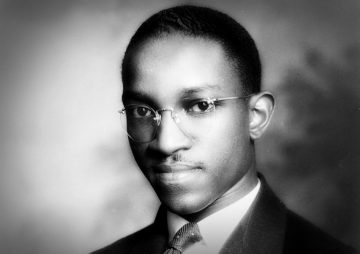

In order to discuss the example, it will be helpful to do a little bit of stage-setting. It involves an incident that took place in the Cosmos Club, a very exclusive Washington, DC, club whose members are drawn from the creme-de-la-creme in the arts, literature, science, and public service. In 1966, the Cosmos Club inducted the eminent historian and long-time professor at Duke University, John Hope Franklin, as its first African American member.

That should be sufficient to set the stage. For the example itself, I’ll turn to a description from a Duke University website celebrating Professor Franklin:

In 1995, on the evening before he was to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom at the White House, Franklin hosted a celebratory dinner party for some of his friends at the Cosmos Club. Some of his guests had not arrived, and Franklin decided to head to the entrance of the Club to look for them. There, an elderly white woman handed Franklin her coat check and demanded that he fetch her coat. Franklin politely informed her that all the Club’s attendants were uniformed and if she handed one of them her coat check, they would be happy to assist her.

The philosophers Mark Schroeder (at the University of Southern California) and Rima Basu (at Claremont McKenna College) have suggested that cases like the one in which the woman believes that Franklin is one of the waitstaff at the Cosmos Club, rather than a distinguished member of that club, involve moral wrongs. The woman’s belief involves a failure to recognize Franklin as having equal status, which is a harm to him.

Okay, so that’s the idea that beliefs can be morally wrong. And it seems plausible to think that, in wronging Franklin through her belief, the woman’s belief was morally problematic. How do we get from that idea to the idea that the moral implications of beliefs can impact the evidence that we have to have in order to hold those beliefs?

Well, Schroeder and Basu suggest that, if you agree with them that beliefs can be morally wrong, then you’re faced with a puzzle. Here’s why.

It’s easy to establish — simply by counting! — that the membership of the Cosmos Club is predominately white, whereas the waitstaff at the Cosmos Club are mostly people of color. So Schroeder and Basu suggest that the woman’s belief was, at least, statistically well-supported. In fact, if you treat frequencies as likelihoods, and likelihoods as evidence, than the evidence that you have that a given person of color that you encounter at the Cosmos Club will be a member of the staff is probably greater than the evidence you have for the belief that it will rain this afternoon on the basis of reading the weather forecast!

So now Schroeder and Basu think that the puzzle arises from the fact that it might seem that we have evidence for the following two claims:

1. The woman’s belief about John Hope Franklin is morally wrong.

2. The woman has good evidence for her belief.

In other words, the conjunction of these two claims poses a puzzle. In fact, Schroeder and Basu think that we must recognize that claims 1 and 2 CANNOT both be true at the same time!

Schroeder and Basu use this supposed fact — that claims 1 and 2 are incompatible — to argue for moral encroachment.

The reason is that, as we’ve already noted, it would seem that the woman at the Cosmos Club has strong statistical support for her belief. So it would seem that the only reason why she wouldn’t have sufficient justification for her belief would stem from the moral implications of her belief. But that just is the thesis of moral encroachment.

So, if it’s true that the amount of evidence you need to be well-supported in believing a certain claim can vary according to the moral status of that claim, the fact that claim 1 is true can be recognized as the reason why claim 2 is FALSE. In other words, moral encroachment EXPLAINS why, if claim 1 is true, claim 2 is false.

So far so good. If the two claims 1 & 2 are mutually incompatible, then that would seem to provide some reason for accepting the thesis of moral encroachment. But why think that? Why not merely say that the woman’s belief is morally wrong despite being pretty well supported by the evidence?

If they’re going to use the supposed incompatibility of the two claims in order to argue for moral encroachment, then Basu and Schroeder need to give some reason for thinking that the moral wrongness of the woman’s belief is incompatible with the woman’s having good evidence for that belief.

Basu and Schroeder’s reason for this comes from thinking about apologies. Suppose, for example, that after Franklin rebuked the woman at the Cosmos Club for her mistaken belief, she gave him an apology. Basu and Schroeder imagine that she might say something like, “Well, I’m sorry for believing that you were on the waitstaff, rather than a member of the Club, even though my belief was epistemically impeccable, short of being true.”

What a philosophically sophisticated apology! In order to evaluate it, we need to understand what it means to say that a belief is “epistemically impeccable, short of being true”. Roughly, it just means something like, “this belief has sufficient evidence to count as knowledge if it were true, but this belief happens to be false.”

Basu and Schroeder don’t think much of this apology. Here’s what they say about it:

This does not seem to us to be much of an apology. And the reason why it does not seem to be much of an apology, it seems to us, is that satisfying every epistemic standard appropriate to belief short of truth looks like the right kind of thing to defeat any presumption of being a wrong.

Basu and Schroeder say that it fails as an apology precisely because, if a belief really was “epistemically impeccable” then the believer would have nothing to apologize for! So, if the woman genuinely thinks that her belief is morally wrong — and therefore that it’s appropriate to apologize for it — then she can’t have met all of the epistemic standards for that belief. Claim 1 and 2 really are incompatible!

And if this is true in the John Hope Franklin case, this would suggest that in any case in which a belief has moral implications, you must meet higher standards in order to be justified in holding the belief. That’s just what moral encroachment says — so Basu and Schroeder have given us an argument for the thesis of moral encroachment.

In fact, it strikes me as quite a neat argument.

Nevertheless, although the argument is indeed neat, I don’t think it’s ultimately a good argument. Here are three reasons why.

The first reason has to do with claim 2, the claim that the woman’s belief that John Hope Franklin was a member of the Cosmos Club’s staff was in fact well-supported by evidence (were it not for the fact that it’s a morally charged belief). Basu and Schroeder think it obvious that claim 2 is true. They’re wrong, however.

If Basu and Schroeder had paid more attention to the actual specifics of Franklin’s case, they would have seen that the woman is criticizable on purely epistemic grounds. Look at this part of the quote from the Duke website: “Franklin politely informed her that all the Club’s attendants were uniformed and if she handed one of them her coat check, they would be happy to assist her.”

What this tells us is that, at the time, Franklin himself suggested to the woman who falsely believed that he was a member of the waitstaff that her belief DIDN’T meet all of the epistemic standards.

The woman didn’t meet the epistemic standards because she ignored clear signs that Franklin wasn’t a member of the waitstaff. Franklin himself explicitly points out to her that he wasn’t wearing a uniform, but we can imagine others. For example, he was standing at the bar and conversing like a member of the club, rather than an employee. Perhaps he was also holding a beverage in his hands, rather than carrying one or more on a tray. We can imagine other relevant details, if we wished.

We can see this also by thinking about this in terms of the relevant class from which to evaluate the likelihood that Franklin was a member of the waitstaff. Basu and Schroeder suggest that, as far as likelihoods are concerned, the woman was behaving appropriately in assessing the chance that any person of color that she encounters at the Cosmos Club is staff, rather than a member. But this is simply not true. The woman should instead have assessed the likelihood that a person of color, not dressed in a staff uniform, nor behaving like a member of the waitstaff, etc., would be staff, rather than a member.

Of course, if the woman in the John Hope Franklin case wasn’t meeting the epistemic standards, there is NO incompatibility between the epistemic and moral standards in this case. In fact, the woman would be criticizable on BOTH moral and epistemic grounds.

It strikes me that the recent case of “picknicking while black” with which we began this discussion of the philosophical thesis of moral encroachment — not to mention the many other cases of whites becoming distressed because they encountered African Americans occupying public spaces — are more like the John Hope Franklin case as it actually occurred. In NONE of those cases, in other words, did the whites have good reason for being distressed.

If I’m sitting in a Starbucks conversing with a friend, or if I’m cooking out at a public park, or if I’m eating lunch in a college lounge, or if I’m napping in a grad school common area, or if I’m sitting by the side of a neighborhood pool, or if I’m a kid selling water, or if I’m mowing a lawn, the best explanation for my behavior is that I’m entitled to be doing what I’m doing.

At least, the default assumption in such cases should be that people going about their business in public spaces are entitled to be doing just that. If you’re going to challenge someone else’s right to occupy that space, then you would have to have very strong evidence for doing so. Certainly, merely feeling uncomfortable would NOT count as sufficient evidence.

So that’s the first reason to worry about Basu and Schroeder’s argument. They haven’t actually presented us with a case in which a belief would be well supported but for the fact that the belief is morally suspect.

Suppose, however, that we do come up with a case in which someone really would have met the evidence standards for knowledge, but happens to have a false belief. Would that be a case where the moral standing of the belief could raise the standards even higher? If so, then Basu and Schroeder would still have the makings of a good argument.

I have to admit that I have trouble thinking of a case in which someone has a morally wrong belief AND has met all of the standards that — were it not for the moral implications of the belief — would make their belief count as knowledge, if only it were true. In fact, as I’ve suggested, the real-world examples of morally problematic beliefs strike me as cases in which the believers HAVEN’T met all of the epistemic standards, regardless of the moral implications of their beliefs.

Suppose, however, that there IS in fact some such case: a belief that is both seemingly epistemically impeccable and morally wrong. Why think that this is, as Basu and Schroeder would have it, problematic?

On the contrary, it seems to me quite possible to suppose that moral requirements might place demands on us above and beyond the purely epistemic demands of acquiring evidence sufficient for knowledge.

A analogous real-world case of this might be in the legal domain. Suppose that 999 out of 1000 people took part in a riot that resulted in the death of a policeman, and all of the 999 were equally culpable in the policeman’s death. Still, most people would not think it acceptable to choose one of the 1000 people at random and convict them solely on the basis of the high statistical probability that they took part in the crime. That inacceptability, however, has little to do with the purely epistemic justification for believing the person chosen at random to be guilty. (I’m indebted to Marcello Di Bello for the idea behind this example.)

Let’s apply this to the case of apologies. Suppose I form the sort of belief that is seemingly epistemically impeccable but morally problematic. I don’t see why I couldn’t say, “It was hurtful for me to believe this about you, and I apologize. As an explanation, although not an excuse, let me just note that the evidence for my belief was very strong. Nevertheless, I should have given you the benefit of the doubt.”

The upshot of all of this is that I just don’t find Basu and Schroeder’s considerations on the basis of their discussion of apologies to be fully convincing. In particular, it doesn’t seem to establish that there is a genuine tension involved in morally wrong beliefs that are seemingly epistemically impeccable.

(This might also explain why, in a recent piece for Aeon, Basu seems to limit herself to arguing for the moral wrongness of certain beliefs, and perhaps of certain ways of forming beliefs about people. At least as I read her Aeon piece, Basu does NOT there argue for the stronger claim that a belief can’t be both epistemically impeccable and morally wrong.)

So that’s two reasons for resisting Basu and Schroeder’s argument for moral encroachment. Here’s one final worry.

This third reason for being hesitant in accepting Basu and Schroeder’s argument for moral encroachment is purely pragmatic. It has to do with what seem to me to be troubling unintended consequences of their position. This is what I mean.

Basu and Schroeder are arguing from a position of well-meaning, liberal sorts of concerns having to do with mutual respect for people of all stripes. However, a structurally identical argument to the one put forward by Basu and Schroeder could be advanced by someone intent on trolling — or worse, someone who genuinely holds despicable views.

Let’s call this third problem the problem of “immoral encroachment”. Here’s an example of what I have in mind:

Offred argues that women are just as intelligent as men and that they should be allowed the freedom to read and develop their intellectual faculties to the same extent as men. Aunt Lydia argues that only women have the ability to bear and nurse children, and that for that reason women should focus their efforts on fostering their unique capacities. Aunt Lydia suggests that, because of the immoral implications of the belief that women are the intellectual equals of men, Offred would need to provide much greater justification in order to be epistemically justified in maintaining her belief in the intellectual equality of women and men.

Now obviously Aunt Lydia’s view is not only morally despicable, but also false. From Aunt Lydia’s perspective, however, the reasoning that she uses against Offred is exactly parallel to the reasoning strategy endorsed by Basu and Schroeder.

Of course, this doesn’t actually mean that the reasoning endorsed by Basu and Schroeder is incorrect. Plugging false premises into a valid argument form may yield a false conclusion. Nevertheless, the person who employs false premises in their reasoning will often be unaware of that fact — just as, in our example, Aunt Lydia is unaware of the despicable nature of her views.

What this means is that this third reason for my hesitation about moral encroachment doesn’t show that the thesis of moral encroachment is false, but rather suggests that appealing to the thesis might not be a useful argumentative strategy when debating with others with whom we disagree.

In fact, it seems to me that we have good reason to separate arguments about the strength of our evidence from arguments about the rightness of our causes, wherever possible. And, as the recent real-world cases of “living while black” seem to demonstrate, just attacking the weak evidential support for many morally problematic beliefs seems to be a perfectly viable strategy for criticizing those beliefs.