by Nickolas Calabrese

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

I don’t know anything about music. I make art, and like many artists I listen to music while working. Nearly every kind of music, but mostly metal for those time-to-get-serious moments. Atmospheric black metal with little discernible speech tends to work best, because it provides a setting such that one can become lost in the droning distortions when working on something. The music I like to hear is that which Kant would endorse as sublime – enormous walls of sound that result in a distractedness where one can go undeterred by outside forces. Of course an fMRI could show what is happening in the brain, what psychically galvanizes me while I listen to music in those moments, but I’m less interested in what’s happening to me as much as what’s happening to it: what happens to artworks when produced to a soundtrack?

Stepping back for a moment, it should be obvious that people of all stripes use music as a tool. Not just those who play instruments or sing or generally make music, but anyone who listens to music. It has an instrumental value in human culture. For instance, when the organ roars over the congregation the parishioners prepare to chant hymns to God. Or when you’re about to do a hard workout and you blast 50 Cent to get in the zone. Perhaps you want to set the mood for making love—easy, Marvin Gaye. When studying, many turn to classical because of it’s melodic flowering as ambient background noise. It is uncontroversial to say that many of us at some point or another use music as an instrument to hype us on what we are actually trying to achieve in that moment.

Music has this ability to influence the way we conduct ourselves in moments of exercise, moments of worship, moments of erotic satisfaction, etc. Aristotle understood this to be an important function for humans, particularly on their moral character. So it’s unsurprising that he included a wide-ranging discussion on the importance of music not in his aesthetic writing, but in his Politics. Under the ‘doctrine of ethos’, which amounts to an antiquated study on the psychology of music, he attempted to determine how different music would affect the attitudes and behavior of people. His view was that music played an important part in how citizens conducted themselves, that music could be helpful or harmful in decision making. To be fair, music was more than just some pop tunes we played in the car while driving home during rush hour. At the time it was meant to inspire people to do good. Even the term “music” itself was in fact derived from the Greek goddesses of inspiration known collectively as the Muses.

When Aristotle contended that music had an ethical consequence on human behavior, he was interested in whether or not, say, aggressive music would cause aggression. Or if loving music would cause happy feelings in the listener. Many of us deal with sadness by turning on Adele. Moments of tranquility can be expressed to a soundtrack of that golden haired angel John Denver. And who hasn’t jumped up to romp when Abba sonically spears you through a discotheque. Music does not condone our behavior, rather it predicts it. There seems to be an appropriate purpose for music and an improper one. You would not expect to hear Slayer’s “Raining Blood” in a Starbucks. It would feel like somebody had made the wrong decision, which is ultimately an indictment of both taste and of ethics.

So then, the question remains of what happens to artworks when we listen to music in the course of their production? Of course there is a case to be made for any atmospheric or internal influence that occurs simultaneous with the production of art. Sure, a cold studio could reflect a frigidity in the work. But I think that music has a more pervasive effect, something more akin to drugs or alcohol, because it seems to temporarily rewire our behavior (and there is plenty of science that reflects this point). Conceptual artist Dan Graham has written and made work about this very effect in pieces like Rock My Religion, a paean to rock and roll that delves into Shaker culture’s spontaneous dancing as a metaphor for 1970s rock’s possession of youth. Graham’s piece functions like a tongue in cheek comparative study, but really gets at some important aspects of punk and rock’s strong influence on youth looking for a way forward after the collapse of the 60’s hippy music. We look for music to free us from something that there might not be words for.

So then, the question remains of what happens to artworks when we listen to music in the course of their production? Of course there is a case to be made for any atmospheric or internal influence that occurs simultaneous with the production of art. Sure, a cold studio could reflect a frigidity in the work. But I think that music has a more pervasive effect, something more akin to drugs or alcohol, because it seems to temporarily rewire our behavior (and there is plenty of science that reflects this point). Conceptual artist Dan Graham has written and made work about this very effect in pieces like Rock My Religion, a paean to rock and roll that delves into Shaker culture’s spontaneous dancing as a metaphor for 1970s rock’s possession of youth. Graham’s piece functions like a tongue in cheek comparative study, but really gets at some important aspects of punk and rock’s strong influence on youth looking for a way forward after the collapse of the 60’s hippy music. We look for music to free us from something that there might not be words for.

Perhaps to a greater degree than Graham, few artists have boasted their indebtedness to music in general, and to rock in particular, as earnestly as the late Steven Parrino. In his slim book of writings and images titled The No Texts (1979-2003), he explores his influences, spending much of it musing on how rock and roll has shaped his output:

“When the Beatles were singing “Taxman,” the Velvet Underground were singing “Heroin.” It’s one thing to sell your out-put after the fact; it’s another to manufacture yourself and your work to fit corporate need. I have no time for the later shit (the Beatles suck).

My relation between Rock and visual art: I will bleed for you.”

Notice how Parrino capitalizes “Rock” and not “visual art”, the latter of which is his given profession. His acknowledgement of what he owes rock is a shrewdly honest fact, one that many artists would probably never admit to. Anecdotally, in the past few weeks I’ve casually asked a number of artists I know if they think that the music they listen to shapes how the work they produce actually looks. I would have imagined a unanimous agreement, but a bunch of them disputed the suggestion Nonetheless, Graham takes a slightly less self-reflexive psychoanalytic position:

“Rock performers electrically unleash anarchic energies and provide a hypnotic ritualistic trance basis for the mass audience—especially when both musicians and audience are under the influence of psychedelic drugs. Such shows suggest the transport of the tent meeting or the Shakers’ deliberate seeking out of the devil in order to purify themselves and ensure communion with God.”

He equates and exaggerates the ritual form, while suggesting the drug-like effect music can have on an impressionable audience, along with the nearly holy effect it can produce through it’s listeners’ actions, just as the Shakers are moved to dance for God. It’s difficult not to consider St. Vitus’ Dance at this juncture too, with possession being an equally apt metaphor for how music has the ability to influence us.

When I am working on art I listen to music. I do the same when I’m writing (at this exact moment I’m listening to the album Aftermath by solo Russian black metal artist Skyforest). I could do roughly anything I do while listening to music without it—I don’t depend on it to make things. But since reading small bits about what artists listen to (everybody from David Hammons’ gratitude for Charlie Parker to Mark Rothko’s almost exclusively listening to Mozart), it seems that the music is sort of already there, like a style that we have absorbed. What I mean is this: the music that we listen to when we work is the stuff that we’ve already absorbed and are in the process of translating visually. I do not mean this as a one-to-one translation—I’m not going to listen to an album and then, literally, attempt to make that album visual. That’s stupid. What I mean is more like an ethos as Aristotle was speaking of, or, maybe more accurately, a pathos. The music of choice becomes more of an emotional adornment that the artist has endorsed and is working alongside.

Then again the question: what happens to artworks under the influence of music? Accurately answering this question is unrealistic. But I feel confident that when I take something in, whether it’s music, liquor, or sunlight, there is a complimentary (or detrimental) effect had on the thing I am producing. Generally speaking, then, the upshot of this proposal is that you are never really solely responsible for the thing you make. When influences are so tangential and contextually temporary, how can you completely own them?

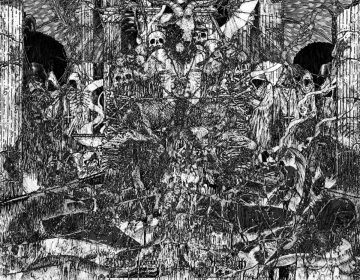

My own taste is for metal. I love the frosty atmosphere of black metal. I love the weird alien nature of progressive metal. I love the cinematic grandeur engendered by post-metal. I love the dripping grey sludge of doom metal. They all share a common celebration of the extreme. Metal, by its very nature, is beyond. Its mere existence is a critique of good taste. Metal is an assault. Metal is the sublime. But even in it’s perverse transgression (and much of metal is naturally transgressive, both sonically and lyrically) it contains kernels of groundedness that channel real problems. It can deliver a passage through murky territory of longing and bleakness, which then could be thrown right into the work I’m making. There is, however indistinct, a transferal from my environment to my work, and I am confident that if my music of choice was not metal, then my work would look different.

My own taste is for metal. I love the frosty atmosphere of black metal. I love the weird alien nature of progressive metal. I love the cinematic grandeur engendered by post-metal. I love the dripping grey sludge of doom metal. They all share a common celebration of the extreme. Metal, by its very nature, is beyond. Its mere existence is a critique of good taste. Metal is an assault. Metal is the sublime. But even in it’s perverse transgression (and much of metal is naturally transgressive, both sonically and lyrically) it contains kernels of groundedness that channel real problems. It can deliver a passage through murky territory of longing and bleakness, which then could be thrown right into the work I’m making. There is, however indistinct, a transferal from my environment to my work, and I am confident that if my music of choice was not metal, then my work would look different.

This prompts a question of normativity: is this how one ought to be making artworks, under the influence of something? Does the acknowledgement of such a pervasive influence in some way devalue the works because of adulteration? Are the works corrupt or impure? At what point does influence become a crutch, like a handicap for someone who cannot actually produce work? And surely this applies to any influence: sex, drugs, alcohol, music, food, the layout of your studio, the clothes you’re wearing, and so on. It seems that everyone owes what they do in part to someone or something else. This amounts to maybe something along the lines of communal ownership of the products of the arts. That does seem to be implied in the notion of making art for other people—why would anyone want to look at someone else’s narcissistic products unless they are actually made for and with us.

This last point might feel like a jump, but bear with me. If an artist makes something in a total vacuum (no man is an island, right?), then their product is totally alienated, something that is not for anyone but the original creator. To be honest, I’m not sure that this kind of work is even possible, since we are each so saturated with influence it would be unimaginable to separate from them, to be in that vacuum. As a thought experiment though, it does enjoy a strange hypothetical existence, work that is made through, and solely for, the person that makes it. So the question of normativity is probably moot, leaving us to just own up to the fact that this music, or that pipe, is significantly responsible for what I’ve made.

One last word on metal, and rock and roll in general, and mettle in particular, and this one comes from the great rock critic Lester Bangs. “Good rock ‘n’ roll is something that makes you feel alive. It’s something that’s human…Rock ‘n’ roll is an attitude, it’s not a musical form of a strict sort. It’s a way of doing things, of approaching things. Writing can be rock ‘n’ roll, or a movie can be rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a way of living your life.” Rock and roll, as Bangs says, is more than just music—in the broadest sense it is actually a way of living life, in the same way that hip hop or pop is. Any approach that an artist takes to their life and their work will contain a multiplicity of influences and attitudes that bubble under the surface, sometimes imperceptibly, always potently.