by Brooks Riley

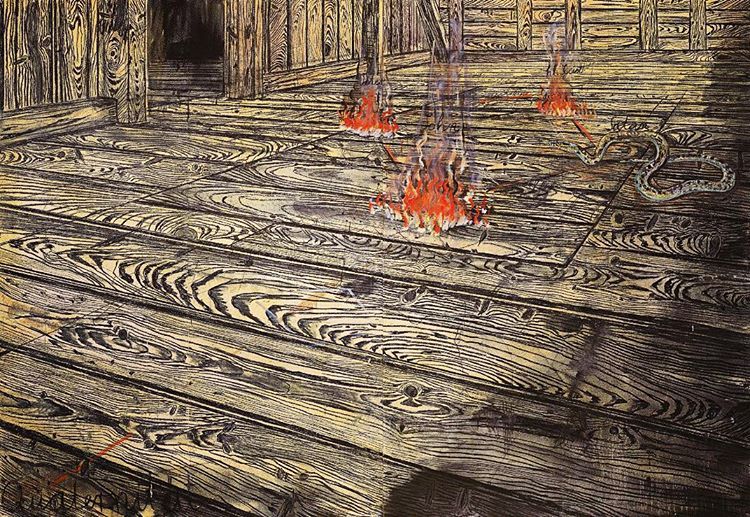

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

‘Our stories begin in the forest,’ Kiefer has said. He means this both literally and figuratively. A man whose name means ‘pine tree’, born in the Black Forest region, comes from a people who inhabited the forests in ancient times. When they left those forests behind, they took the wood with them to build, among other things, their attics and their cathedrals, both shareholders of enduring legacies.

Quaternity is one of the few paintings that addresses a lapsed religion now stored away in Kiefer’s mind, his attic—an attic he once lived in as a student, and one he has revived in other paintings. It is only one of his many recurring motifs that serve as conduits for his multiple concerns and thought processes. Myths of all kinds are stored in that iconic space, along with the first- and second-hand memories of history, philosophy, poetry, metaphysics, astrophysics, mysticism and alchemy.

The fire at Notre Dame has spawned countless essays attempting to find meaning in the near obliteration of an emblem of civilization dating from a time when civilization was still possible.

The search for meaning is what separates us from the animals. It is something we do instinctively, which leads to the next question: Should art mean something? Should an artist strive for meaning in his work? One of the most meaningful works of the 20th century, Picasso’s Guernica compels viewers to examine and remember a horror that implicates us all through the protracted, ongoing zeitgeist of such events. The gigantic canvas is both a depiction of terror and an aesthetic triumph, calling forth the paradox of beauty endowed with appalling content. It lacks metaphor. It doesn’t pose a question. It states its case, take it or leave it.

Picasso said of Guernica: If you give a meaning to certain things in my paintings it may be very true, but it is not my idea to give this meaning. What ideas and conclusions you have got I obtained too, but instinctively, unconsciously. I make the painting for the painting. I paint the objects for what they are.

Anselm Kiefer too rejects the idea of intended meaning, although his works abound with metaphor: I have no intended impact. None at all. Each viewer can create their own experience, their own work from what they see. It’s nice if people understand the ideas and references behind my work, but it’s absolutely not necessary.

What is necessary is Kiefer’s own search for meaning, the urgency behind his ferocious prolificity. ‘Why are we here?’ is a question he often poses, accompanied by a ‘desperation’ to understand that propels him with equal urgency to both his vast library as well as to his voluminous ateliers. His search takes him out to the stars and back to the geological timeline of the Earth itself.

Meaning is sometimes like music, difficult to describe in words. Its power is not necessarily diminished by that indescribability. And we often don’t know where meaning is coming from. Certain neurons fire when the eye is confronted with the improbable, the inexplicable, the ineffable, and it is always searching for interpretive elements to offset the affront to its pictorial expectations. For every viewer, meaning is bespoke, something unique achieved through a neurochemical reaction between a person’s past, memory, knowledge, preferences, emotional constitution and the work of art he or she beholds.

Explosions can be chemical reactions too. If a detonation causes the sudden, rapid release of energy, then no moment could have been more auspicious for Anselm Kiefer than the night of his birth, when his house was bombed by the Allies. What emerged from the collision of these two antithetical events would not only cover the landscape of his childhood with the detritus of destruction, but also energize a life-long, explosive body of work as much about those events as they are about the history reverberating from them—his own, that of Germany, and beyond—with special emphasis on beyond. They form the foundations of his philosophy of art in a way that has as much to do with the way his art is created as it does with the finished works. Kiefer is a living metaphor for the dual nature of destruction, as both omega and alpha. ‘Ruins are a beginning for me.’ He has said this often. They were the point of departure from the night of his birth. And they are at the center of nearly every work he has produced ever since.

I remember those ruins. I was four years old when my parents and I stayed overnight in a German city on our way from Bremerhaven to Paris, where we were living. I remember looking out the window and seeing the black skeletons of once whole buildings outlined against the somber night glow of the city, gloomy and even frightening–the stuff of nightmares or mystery. I remember thinking, ‘If this hotel is intact, what is all that destruction across the street?’ War was still an unknown word for me.

But not for Kiefer, then living not far away (we are only months apart in age). The war’s destruction which defined his immediate environment must have cordoned off a special place in his brain, where he would return as an adult to find the nourishment for his art. Even now, Kiefer loves looking at the films and photographs of the devastation of postwar Germany. Those ruins were his playground, his early introduction to the substances he would later use, the dirt, the crumbling bricks, the plaster, the chaos of displaced order, the damaged goods. For a child who knew nothing else, ruins didn’t represent loss and devastation, they were the magical stuff of childhood fantasy, something upon which to construct an own world.

Ruins are imbued with an aesthetic all their own. Long before I saw Kiefer’s work, I was somehow preparing for it, on train rides from New York to Washington, when I became haunted by the ghostly industrial wasteland of New Jersey—the abandoned factories, the twisted metal, the rust, the sidings to nowhere reclaimed by weeds, the broken windows. Whenever I saw this chaotic terrain, I instantly wanted to photograph it, to capture the beauty of deterioration that was awaiting its Cinderella moment. Since then, the photographic exploration of abandoned spaces has become a genre all its own, a nostalgia for decay. Not surprisingly, Kiefer has a fondness for Detroit, another scarred victim of time and entropy.

The child Kiefer dug tunnels under ruins, which gave rise to his first subconsciously conceptual work: He drew something on a piece of paper, placed it in his tunnel and then closed it off forever. The man Kiefer has been digging too, a network of tunnels over 200 acres of land in the south of France, in Barjac. Tunnels are rife with metaphoric potential—digging deeper into a subject, but also going deeper into places where things are hidden—secrets, thoughts, history, meaning, shame—embedded in crafted chiaroscuro beauty that evolves with every twist and turn along the subterranean pathways.

Kiefer is still digging—and playing. The playgrounds have become bigger over time, the ‘ruins’ now of his own making, grander and powered with intentional upheaval. In addition to Barjac, and his brick factory in Buchen, he owns a vast 400,000-square-foot former department store warehouse outside of Paris and a newer workshop in Portugal. His works and his spaces have exploded in size and substance, achieving a monumentality that arouses suspicion, but only in those for whom size matters.

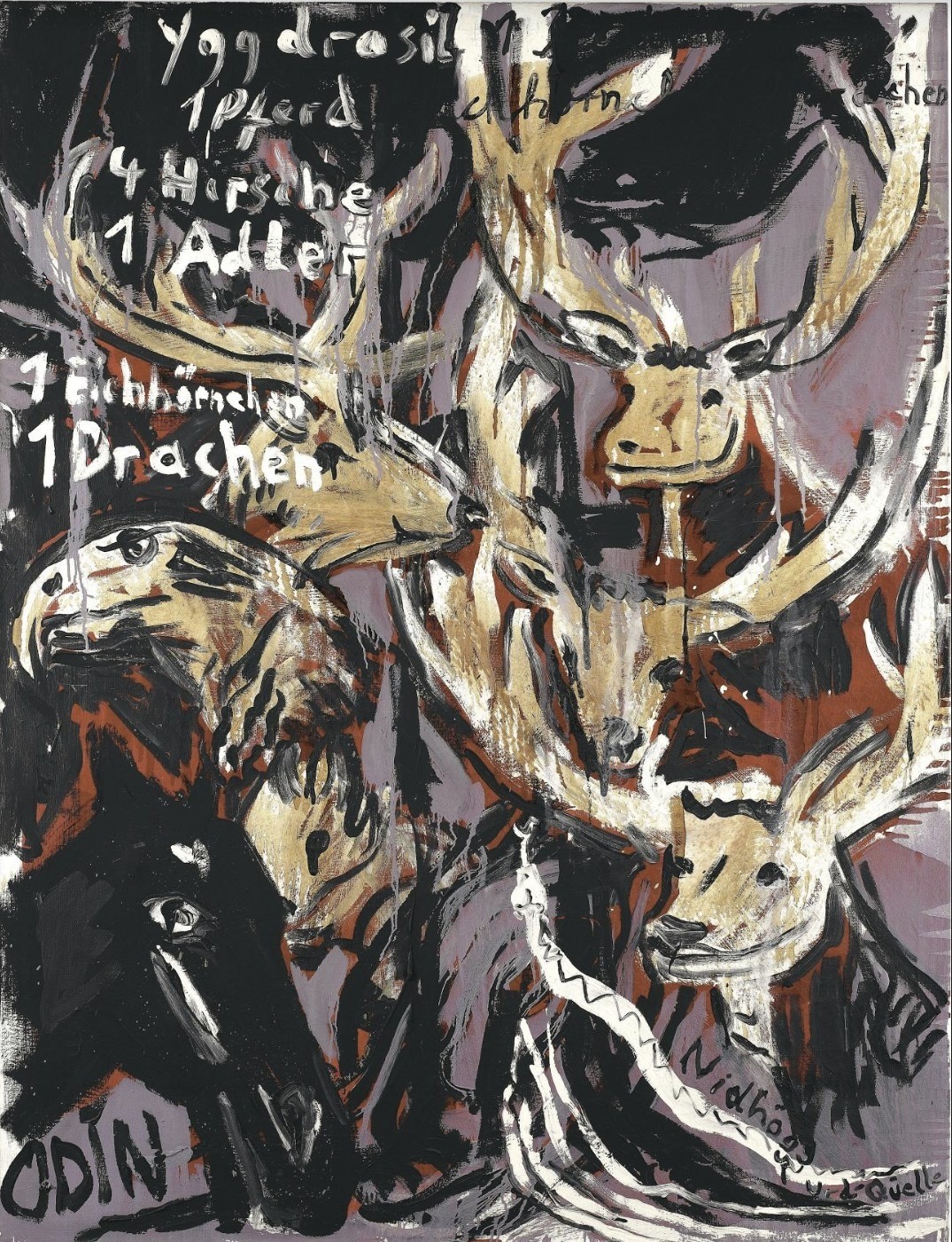

I first saw Kiefer’s work, at MOMA in 1988, at a time when I was exploring the power of myth in the works of Jung, Wagner and Joseph Campbell. The Yggdrasil of Germanic folklore, the world ash tree of the creation myth, had become a personal icon—and my very first internet password. It was my secret, or so I thought, until I saw a worked entitled Yggdrasil in that Kiefer show. It wasn’t the most impressive of his works (it wasn’t even his best Yggdrasil), but it served as a key into his mind that made the grander works resonate with more than simple recognition.

It’s difficult to stand in front of a Kiefer painting without hyperventilating. The bombardment of myth, thought, history, philosophy, mysticism, metaphor, poetry and omen, together with the tactile spirit of materials like lead, straw, dust, sand, ash, in multiple layers, coaxed by his alchemical processes of scorching, electrolyzing, melting, soldering, endow his works with an impact and energy completely at odds with the pleasant, colorful, often figurative works that dominate the canon of modern art—the Rauschenbergs, the Warhols, the Basquiats, the Hockneys, the Rothkos.

His Affekte are both exalting and devastating, ranging from deep sorrow or sublime wonder to intense yearning. This is art in capital letters, dwarfing the singular ambitions of other painters of his generation, returning beauty to art in a new emotional way as beauty about something, infusing these works with poetic meaning, terror, tragedy, fury, symbolism.

The clash of form and content in the paintings is like an explosion, the result of brutality perpetrated on the canvas—molten lead poured over lovely images, deep machete slashes, electrolysis, fire, weather, multiple layers of paint and all those other substances that are on standby, neatly stored in open boxes in all his workshops. Kiefer holds on to everything, even the 35-year-old pile of straw he collected for his signature Margarete-Shulamith paintings.

If Kiefer’s artistic odyssey began in an attic, it quickly spread, like that fire last week, to other locations, fostering other motifs: forests, cities, landscapes, oceans, heavens, and the cosmos. His references spread too, to the Kaballah, Talmud and Old Testament, to poets like Paul Celan or Velimir Chlebnikov, to the cosmic musings of Robert Fludd, to obscure philosophers like the Italian Andrea Emo.

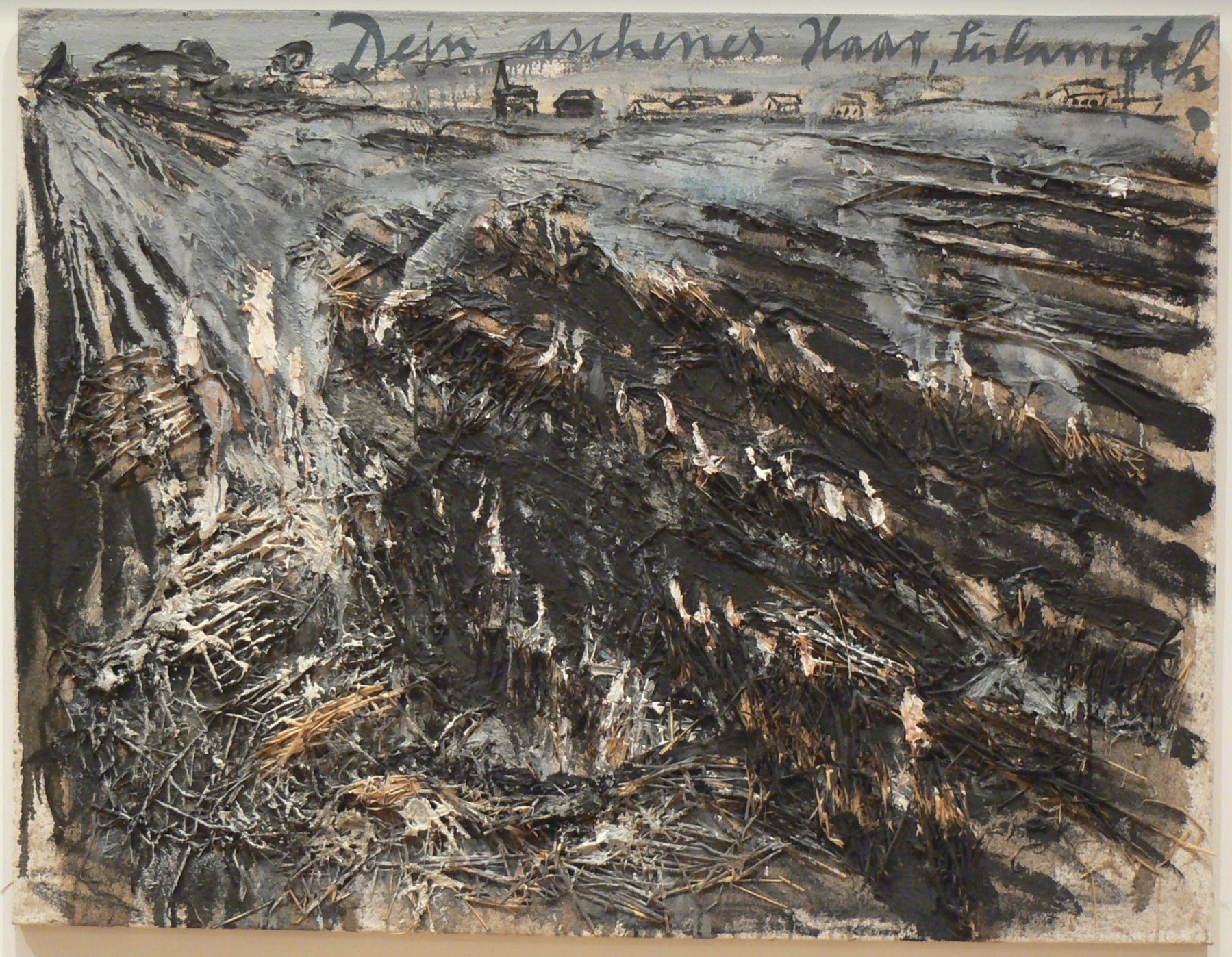

One major recurring motif is overpowering in its complexity: the furrowed landscape of fields, with their perspective-driven rows of orderly growth that evoke the word cultivation and its kinship to culture. This is no ordinary device, and Kiefer challenges our perception of civilization by rendering this symbol of programmed fertility into endless landscapes of devastation, scorched earth, dead plants, winter sleepers, and other variations of human Ordnung imposed on the earth. One could fantasize about rows of prisoners marching to their death, or rows of gravestones of the murdered. Or rows of the like-minded marching to the wrong tune. Or runes, as suggested in one title. Just as he layers paint, Kiefer piles on layers of suggested meaning into a single motif, from one canvas to the next.

Like a poet, Kiefer is always tinkering with his imagery. His catalog of motifs, like the leitmotifs of Wagner, are infused with new resonance each time he uses them. The thirty Margarete-Shulamith paintings devoted to the last line of the poem Death Fugue by Paul Celan explore a tragedy of modern history. The desiccated hair of Margarete (the Gretchen of Goethe’s Faust) depicted by straw, has lost its life and luster through the burning of Shulamith’s ashen hair, implying that the Holocaust has destroyed not one, but two cultures that had thrived together on the once fertile, cultivated ground.

Assault may be the wrong word to describe a confrontation with Kiefer’s work. There is the feeling of being pulled relentlessly into a vortex or a maelstrom of references where the forces of shared culture and universal memory swirl around us in a provocative physical chaos that is far from abstract, disturbing and confirming our worst fears and desires. The works come to us and we go to them, meeting somewhere in a no-man’s land where imagination and interpretation take over.

Kiefer speaks in paradoxes, literally and artistically; he feeds on them and gains nourishment from them. His works invite paradoxical thinking in the beholder as well. How else could his earthy tones render primary colors insignificant by comparison? How else could the horizontal seem so vertiginous? He thrives on the tension created by extremes—microcosm and macrocosm, illusion and reality, destruction and rebirth, life and death, heaven and earth, past and future, form and content, process and product, beauty and atrocity, chaos and order.

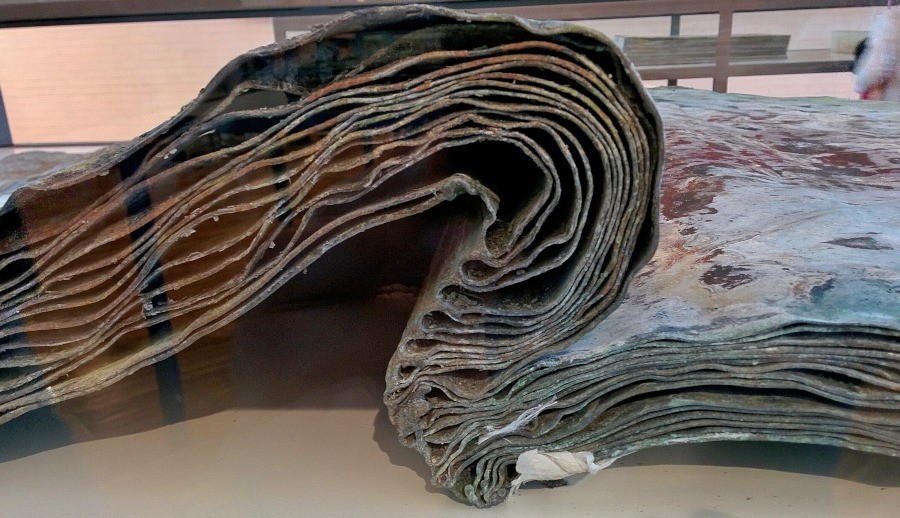

Alchemy itself is a paradox, turning lead into gold the most paradoxical of all transformations. But for Kiefer, lead is the gold. Nowhere is this more evident than in his leaden books with their implied priceless content of knowledge and thought. Nothing says gravitas quite like lead. A different cathedral played a role in these works: When the roof of the huge gothic Cologne cathedral was replaced, Kiefer bought all the discarded lead, 40 truckloads full, to create those books which so appeal to writers like Orhan Pamuk or Karl Ove Knausgård, or the historian Simon Schama, who devoted a whole section of his Landscape and Memory to Kiefer’s work. Kiefer’s love of books brings him in contact with the texts that form a unique collective memory of which he is both creator and curator, transformed into imagery that envelops the viewer with the music of meaning.

For years Kiefer could not be pigeonholed into the evolving history of modern art as exemplified by museum group shows or a fickle art market. Despite labels like Junge Wilde, Neo-expressionist or Neo-romanticist, he was an anomaly, an outlier. Now he has become his own movement, an Alte Wilde of one, with a vast oeuvre that cannot be relegated to the corner of contemporary art history any more than Leonardo or Michelangelo can be relegated to a corner of the Renaissance.

Kiefer was reclusive for most of his career, refusing interviews. It’s one of the things I always admired about him, even if it was frustrating not to know more about the man behind the art. Now that he has emerged from self-imposed isolation, a surprisingly affable man who laughs impulsively is not what I expected. On closer examination, his humor is ironic, that irony a by-product of thinking in paradoxes.

If he is a quintessential German artist, it is not just because he addresses the mythology and atrocities stored in the attic of his German psyche, it is also because he explores new worlds, like Goethe or Humboldt before him, searching for the poetry and meanings that lie in texts and narratives and biology of other cultures, philosophy, history, science and obscure places, all far from a Teutonic context. Kiefer is a universal tourist of the mind, a Faust without a pact, always in search of one more sublime paradox to explain existence. His frequent use of the word ‘desperate’, embellishes a need-to-know that fires his single-minded drive to arrive at an epiphany. Art is longing. You never arrive, but you keep going in the hope that you will, a statement that echoes the eternal Sehnsucht of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

Dürer encircles me like a thick fog, heavy with the mist of hints into his mind, passions and emotions. Every time I see his work, I feel that atmospheric embrace even at the distance of centuries. The Kiefer effect is something else. His canvases find the dark corners of my mind, forcing alchemical reactions within my own internal contradictions, rousing the borrowed memories of a cultural heritage all too familiar and yet exotically foreign too. His repeated motifs establish a poetic dimension I have learned to traverse in my own search for meaning.

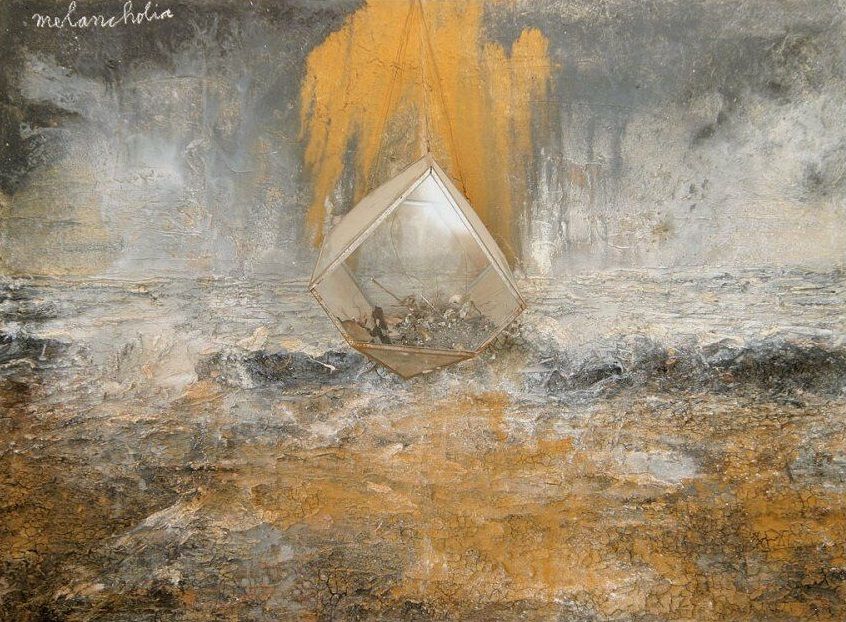

Dürer and Kiefer have much in common: a thirst for knowledge and the tireless drive to create. Kiefer has borrowed Dürer’s polyhedron from Melancolia I in several works. The ghost of Caspar David Friedrich seems to haunt him as well. One of my favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Eismeer, presages elements of Kiefer’s work—the chaos, the layering, the colors. Both painters savor ruins.

Nearly all of Kiefer’s work explores duality and paradox—a fact that has led some critics to suspect a personal duality toward the myths he exposes and the abuse they have endured through misuse by movements, governments and evil individuals. The myths themselves are not culpable. Like Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung, another Kiefer subject, they are often cautionary tales against the very villains who co-opt them. They endure as fundamental nourishment to our inner lives just as all narratives embellish our sense of self and our place in the cosmos.

At a time when history is out of control, Kiefer’s evocations and excavations of the past might seem remote. But what of his evocations of the future? Several 2016 homages to Rodin’s only book, Les Cathédrales de France, are eerily prophetic of the viral images from Paris last week. As the title of a BBC documentary on Kiefer, Remembering the Future, seems to imply, poets may be the only true prophets.

Recommended links for the interested:

Kiefer: Remembering the Future, a BBC documentary about Kiefer.

A seven-minute slide show of works, to be watched full screen without sound

Museum of Modern Art catalog of the 1988 Kiefer exhibition I saw.

Watch Kiefer pour molten lead on an unfinished painting