by Sarah Firisen

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them, “Autopilot technology already does most of the work once a plane is aloft, and has no trouble landing an airliner even in rough weather and limited visibility.” But the average person either doesn’t realize that, or they console themselves with the knowledge that humans are in the cockpit and could take over. Though perhaps the more rational thought would be to console themselves that if something happens to the pilot, the computer could take over. Maybe it’s the more rational thought, but most of us aren’t perfectly rational beings.

My seventy-something year old uncle, who still uses a flip phone, was talking to me a while ago about self-driving cars. He was adamant that he didn’t want to put his fate in the hands of a computer, he didn’t trust them. My question to him was “but you trust other people in cars?” Because self-driving cars don’t have to be 100% accurate, they just have to be better than people, and they already are. People get drunk, they get tired, they’re distracted, they’re looking down at their phones. Computers won’t do any of those things. And yet my uncle couldn’t be persuaded. He fundamentally doesn’t trust computers. And of course, he’s not alone. More and more of our lives have highly automated elements to them, “Autopilot technology already does most of the work once a plane is aloft, and has no trouble landing an airliner even in rough weather and limited visibility.” But the average person either doesn’t realize that, or they console themselves with the knowledge that humans are in the cockpit and could take over. Though perhaps the more rational thought would be to console themselves that if something happens to the pilot, the computer could take over. Maybe it’s the more rational thought, but most of us aren’t perfectly rational beings.

Society is predicated on a level of trust, we couldn’t function as communities, as towns, as countries, if it wasn’t. We trust that the food we buy in the store isn’t contaminated, we trust that the water coming out of our taps won’t make us sick, we trust that law enforcement will protect us, we trust that we pay our taxes and that money isn’t embezzled. Sometimes, this trust turns out to be misplaced, just ask the people of Flint, but even when that happens and we’re all appalled, we mostly go back to a state of trust. Because it’s hard to function in society if you don’t.

To live with no trust in other people is to relegate yourself to living a hermetic existence in a cabin in the woods, “The capacity to trust in other humans we don’t know is why our species dominates the planet. We are ingenious, and our relentless search for new and better technologies spurs us on. But ingenuity alone would not be sufficient without our knack for cooperating in large numbers, and our capacity to tame dangerous forces, such as electricity, to safe and valuable ends. To invent the modern world, we have had to invent the complex web of laws, regulations, industry practices and societal norms that make it possible to rely on our fellow humans.“

But what is trust? The OED defines trust as “firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability, or strength of someone or something.” Many people these days will tell you that they don’t trust the government. And they may have good reasons to feel this way. Yet, mostly, they still act in a way that implies some level of trust. And for most people, that’s probably because the alternative to being part of society is unpalatable and so they either put the distrust aside or live with it. And so maybe the key words in the OED’s definition are “firm belief”. Where is your belief on a sliding scale? If you have zero belief in the trustworthiness of the government, maybe you do go and live in a cabin in the woods. Otherwise, you vote according to your level of trust in governments ability and willingness to fulfill its promises.

In the very good Canadian sci fi thriller, Travelers, the future is a bleak wasteland of scant resources and humans have chosen to have an AI overlord, the Director, allocate resources and protect them. There is an anti-Director faction that would rather be masters of their own fate and try to destroy the Director. It’s not clear that they think they’d do a better job, but rather that they believe it’s a job that humans should be doing for themselves. And this seems like a pretty good allegory for the automation inflection point we’re in now, or are certainly moving into.

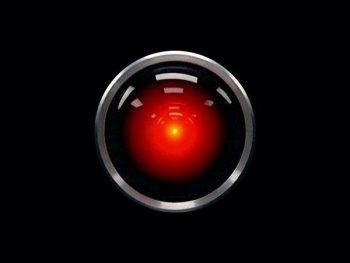

So when we talk about trusting computers, trusting automation, trusting AI, are we holding it to a higher standard that we hold humans? Like my uncle, are we expecting absolute trustworthiness from computers in a way that we don’t from people? Of course it’s true, that it’s the very power of modern computing that causes many people to hold this double-standard; one untrustworthy person can only do so much damage (usually), but an untrustworthy highly advanced AI could do a lot of damage. In the movie 2001: Space Odyssey, the computer HAL starts off as a dependable member of the crew but eventually kills them all to prevent them from turning it off. This idea of the extremely powerful computer program that eventually outsmarts humans and then turns on them is repeated over and over in popular culture. The message we’ve been receiving for years is that distrust of computers is the sensible position to take.

But at least, can’t a case be made that, unlike people, AI has no built-in bias, that it’ll be fair and even handed in its decisions? It won’t act in self-interest, it won’t make decisions based on any form of tribal preference, whether that be race, country or religion. This turns out not to be true, “AI systems are only as good as the data we put into them. Bad data can contain implicit racial, gender, or ideological biases. Many AI systems will continue to be trained using bad data, making this an ongoing problem. “ So as we put an increasing amount of trust in automation, whether we realize it or not or even like it or not, we do need to ensure that, like the people we trust, it’s evolving and acting within the ethical and legal frameworks we’ve agreed to as a society while not perpetuating the conscious and unconscious bias that people bring along with them.

But to go back to my uncle and the self-driving car, as this article lays out, we’re often not sure ourselves what the “right” action is. The philosophical conundrum, The Trolley Problem, as hilariously demonstrated in the show The Good Place, does not have a simple answer for most people, so why do we think it would be either an easy decision for a computer to make, or an easy decision to program into a computer? “Trolley-type dilemmas are wildly unrealistic. Nonetheless, in the future there may be a few occasions when the driverless car does have to make a choice – which way to swerve, who to harm, or who to risk harming? These questions raise many more. What kind of ethics should we programme into the car? How should we value the life of the driver compared to bystanders or passengers in other cars?” Perhaps part of this dilemma is that when people make the decision, they make it in a very individual way, perhaps based on very personal and particular circumstances. And if, there’s no perfect choice, we can live with them having tried to make the best of a bad situation in the moment. But to program a computer to make this decision, which it will then do consistently given the same input data, is for us to have to collectively think through this scenario and preemptively weigh up one person’s life against another’s and then know that’s the decision that will then get made every time. And that’s a pretty uncomfortable choice to have to make. And as this article goes on to posit, who makes that decision? The car maker? The government? Do you walk into a car showroom and have to make that ethical decision then and there and know that’s then how your car is programmed?

Ultimately, these kinds of decisions will have to be made, one way or another. And sooner rather than later. And just as with our trust in other people, we will probably have to live with imperfect trust in the computers that we’re allowing to have an increasing presence in our lives. However, there are clearly processes that can be put into place to allow that trust to grow; transparency around how and where AI is being used, around how our data is being collected and used and control over that data such as the European GDPR rules around data protection would at least be a start. Finland has started an interesting program to try to democratize AI, “the government wants to rebuild the country’s economy around the high-end opportunities of artificial intelligence, and has launched a national program to train 1 percent of the population — that’s 55,000 people — in the basics of A.I….A growing movement across industry and academia believes that A.I. needs to be treated like any other “public awareness” program — just like the scheme rolled out in Finland.” Demystifying the technology would at least be a first step in helping to build trust in it.