by Bill Benzon

In The Only Game in Town: Digital Criticism Comes of Age I argued that digital criticism was the most important development in contemporary literary studies because it is the only line of investigation that presents us with new objects of thought. I’m continuing that argument in this post, where I consider some of the new conceptual objects in Matthew Jockers, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History (2013).

Jockers undertakes a variety of inquiries into a corpus of 3346 19th Century Novels from America, Britain, Ireland, and Scotland, examining style, theme, and influence. Though he considers the possibility that literary culture evolves in a manner similar to that of life forms, he rejects the idea (pp. 171-172). Not only do I think Jockers is mistaken on that point, but I think that his analytic and descriptive work provides strong evidence not only for conceptualizing literary history as an evolutionary process, but that that process is directional (at least for the corpus Jockers examines). The purpose of this essay is to sketch out that case by reinterpreting some of Jockers’ results.

Note however that I do not intend to provide the required evolutionary model, though I do have some thoughts on how to do so (see the suggested readings at the end). I’ve only explained why I believe such an account is necessary.

Caveat: This is an unusually long post, so you might want have coffee or wine, your pleasure, readily at hand. Also, the argument is basically mathematical, though informally expressed, and mostly through diagrams, which are central to digital criticsm.

Does Culture Evolve?

Let me set the stage by quoting a passage from Tim Lewens’ excellent review of cultural evolution in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2014):

The prima-facie case for cultural evolutionary theories is irresistible. Members of our own species are able to survive and reproduce in part because of habits, know-how and technology that are not only maintained by learning from others, they are initially generated as part of a cumulative project that builds on discoveries made by others. And our own species also contains sub-groups with different habits, know-how and technologies, which are once again generated and maintained through social learning. The question is not so much whether cultural evolution is important, but how theories of cultural evolution should be fashioned, and how they should be related to more traditional understandings of organic evolution.

The alternative, Lewens suggests later on, is that “cultural change, and the influence of cultural change on other aspects of the human species, are best understood through a series of individual narratives.” Lewens rejects that notion, and so do I – and I’ll address that specific alternative, individual narratives, a bit later.

Before going on, however, I want to dispose of the most common objection to the idea of cultural evolution:

The explanatory point of evolutionary dynamics is that it gives us design without a designer, without intention. But isn’t culture consciously and deliberately designed and created?

Cultural artifacts (whether physical things, such as books or drawings, or events, such as rituals or musical performances) are deliberately designed and created by human agents and thus are not the result of a blind evolutionary process. That is true. But whether or not any of those artifacts are retained in a group’s repertoire is a matter beyond the will and design of individual creators. The process of cultural selection is independent from that of artifact creation.

Those many 19th Century novels that are now forgotten were created with as much deliberation and intentional design as those few that we still read and used as the basis for other cultural products, such as movies and, e.g. zombified parodies (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies). Whatever it is that distinguishes the novels with lasting cultural salience from the more ephemeral ones, it isn’t the mere fact of deliberation and design.

Macroanalysis: Styles

Now let us consider Matthew Jockers’ Macroanalysis. Working with a large corpus of over 3000 texts Jockers investigated two kinds of traits in those texts, stylistic and thematic.

The statistical investigation of style goes back to the mid 1960s when Mosteller and Wallace worked on Federalist Papers with uncertain authorship (15 out of 85). Subsequent research has shown that high-frequency words (mostly grammatical function words) and punctuation marks are most useful features for identifying style. Just why those features are most useful is an interesting question, and Jockers has some discussion of the matter here and there as appropriate in particular cases. But I’m simply going to treat the matter as an empirical fact. Nor, for that matter, am I going to attempt to summarize the techniques Jockers uses (he does that on pp. 68 ff.).

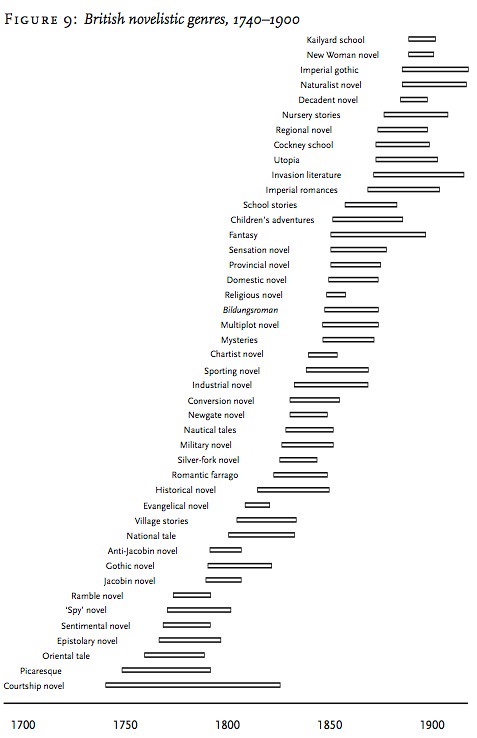

Let us consider a specific piece of work, Jockers’ reconsideration of a claim that Franco Mortti made in Graphs, Maps, Trees (2005). Here’s Moretti’s Figure 9 (p. 19):

Here’s what Moretti says about it (pp. 18-19):

Forty-four genres over 160 years; but instead of finding one new genre every four years or so, over two thirds of them cluster in just thirty years, divided in six major bursts of creativity: the late 1760s, early 1790s, late 1820s, 1850, early 1870s, and mid-late 1880s. And the genres also tend to disappear in clusters: with the exception of the turbulence of 1790–1810, a rather regular changing of the guard takes place, where half a dozen genres quickly leave the scene, as many move in, and then remain in place for twenty-five years or so. Instead of changing all the time and a little at a time, then, the system stands still for decades, and is then ‘punctuated’ by brief bursts of invention: forms change once, rapidly, across the board, and then repeat themselves for two– three decades: ‘normal literature’, we could call it, in analogy to Kuhn’s normal science.

Jockers looked into this phenomenon using a corpus of 106 novels that Moretti had classed into genres: historical, Newgate, Jacobin, Gothic, silver-fork, sensation, Bildungsroman, industrial, evangelical, national, and anti-Jacobin. Here Jockers’ his Table 6.4, showing genres distributed by decade (p. 85):

| 1780s | 1790s | 1800s | 1810s | 1820s | 1830s | 1840s | 1850s | 1860s | 1870s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Goth | 15 | 54 | 8 | 15 | 8 | |||||

| Jaco | 100 | |||||||||

| Anti | 40 | 60 | ||||||||

| Evan | 33 | 67 | ||||||||

| Natl | 38 | 63 | ||||||||

| Hist | 4 | 44 | 33 | 7 | 11 | |||||

| Silv | 11 | 56 | 22 | 11 | ||||||

| Newg | 86 | 14 | ||||||||

| Indu | 44 | 44 | 11 | |||||||

| Bild | 27 | 36 | 18 | 18 | ||||||

| Sens | 20 | 80 |

Notice first of all that the numerical values are percentages, not absolute number of texts, and that it is the row values that add up to 100%. Thus, for example, 100% of the Jacobin novels were published in the 1790s and 40% of the anti-Jacobin novels were published in the 1790s and 60% in the 1800s, and so forth. That table Jockers notes, looks rather like Moretti’s Figure 9, except that it has percentages added. What’s interesting is that novels in each genre are not spread evenly across decades–which in any event, as Jockers notes, are somewhat arbitrary time periods.

Jockers then presents another table, Table 6.5 (p. 87) designed so that the percentages in each column add up to 100%:

| 1780s | 1790s | 1800s | 1810s | 1820s | 1830s | 1840s | 1850s | 1860s | 1870s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Goth | 100 | 39 | 11 | 9 | 7 | |||||

| Jaco | 50 | |||||||||

| Anti | 11 | 33 | ||||||||

| Evan | 11 | 9 | ||||||||

| Natl | 33 | 23 | ||||||||

| Hist | 11 | 55 | 60 | 20 | 25 | |||||

| Silv | 5 | 33 | 20 | 8 | ||||||

| Newg | 60 | 8 | ||||||||

| Indu | 33 | 44 | 14 | |||||||

| Bild | 25 | 44 | 29 | 100 | ||||||

| Sens | 11 | 57 |

What we see is that genres are not equally represented in each decade. Notice, for example, that the national (Natl) novel is distributed 38% and 63% over the decades 1800 and 1810 (Table 6.4) respectively. While it constitutes 33% of the texts in the 1800s, its relative contribution to the 1810s is smaller (Table 6.5), despite the face that that’s when a greater portion of its output appeared.

Morretti’s 2005 is thus confirmed, though only for a limited set of texts and genres. Genres rise and fall over time and have a life that spans a generation, more or less.

Macroanalysis: Themes

Let’s set this aside look at how Jockers investigated themes. He uses a sophisticated statistical technique called topic modeling to identify clusters of words that occur together though many different texts. The computer simply delivers lists of words, along with a weighting of how important each word is in the topic. Those words are said to constitute a theme. It is up to the investigator to interpret that cluster, to characterize what the theme is about.

Rather than attempt to explain how topic modeling works, I’m simply going to present a few examples of his results. Jockers explains the technique in Macroanalysis (pp. 122 ff.).

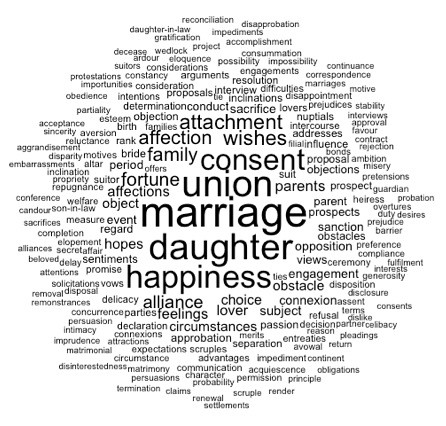

Working with his corpus of 3346 American, British, Irish and Scottish novels, Jockers developed a model having 500 topics. Here’s the cluster for one topic (the size of the word is proportional to its frequency in the topic), which Jockers calls MARRIAGE 1 (there’s also a MARRIAGE and a MARRIAGE 2 topic):

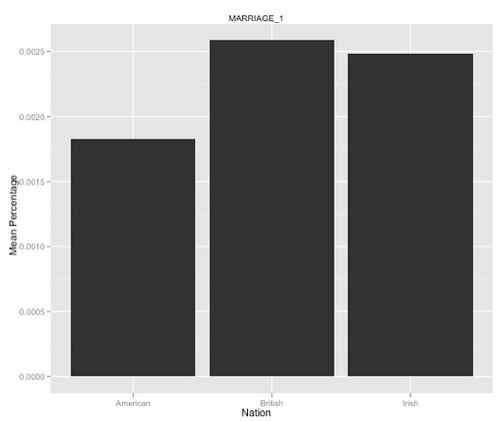

This chart shows that it occurs more frequently in British and Irish texts than in American:

That difference, of course, requires an explanation, but that’s outside the scope of this essay. That’s one of many observations for which an evolutionary account must provide an explanation. In this particular case, as in many others, there is an existing historical literature to start with; Leslie Fiedler’s now classic Love and Death in the American Novel (1966) speaks directly, and at length, to this difference.

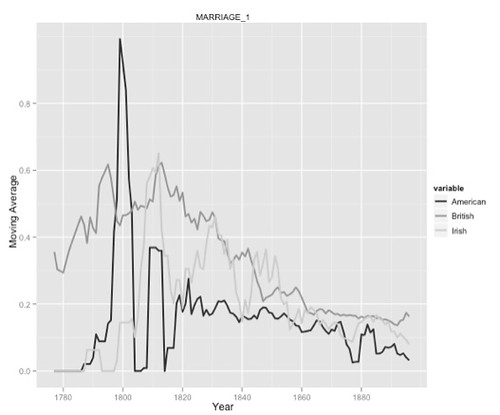

This graph shows the prevalence of that topic over time:

Roughly speaking, the topic was most prevalent early in the 19th Century (about a fifth of the way from the left-hand side of the chart), and then declines in frequency. That too requires an explanation, but that too is beyond the scope of this essay. More generally, each topic has a temporal distribution and those distributions need to be explained: Why are some themes culturally salient at a given time, and other themes not?

Jockers has this kind of data about each of 500 topics that occur in those 19th Century novels. He’s placed that information on a web page where anyone can look up a particular theme. I urge you to go there and explore this data for yourself.

* * * * *

In his ninth chapter, Influence, Jockers combines results from both his stylistic and thematic investigations in an effort to understand the pattern of influence of earlier upon later writers. His argument is that a text will be very similar to the texts that influence it and that we can measure similarity by using the stylistic and thematic features identified in those investigations. My argument is that, whatever that analytic work says about influence, which is a traditional topic in literary criticism, it can be fruitfully interpreted as evidence that literary culture changes through an evolutionary process and that, for this corpus, that process is directional.

Given that Jockers himself does not undertake such an analysis, we should specify reason for doing so. What is it about Jockers’ analysis that admits, and even calls for, such an interpretation?

Some Simple (Imaginary) Examples

To understand that we need to take a careful look at what Jockers did in his investigation of similarity between texts. To that end I am going to give simplified account based on imaginary examples.

The general idea is to measure each text on a number of traits or features and then compare measurements. Jockers has identified a combined total of almost 600 stylistic and thematic traits (each of which can be characterized by a numerical value) in his corpus of over 3000 works. Let us imagine a very simple case where we’re measuring a handful of texts on only two traits. It doesn’t matter what those traits are. But would be nice to put meaningful labels on the X and Y-axes of our feature space. Let’s say we’ve got one stylistic trait, the frequency of the word “she,” and one thematic trait, the proportion of words in the text that are taken from the MARRIAGE 1 topic.

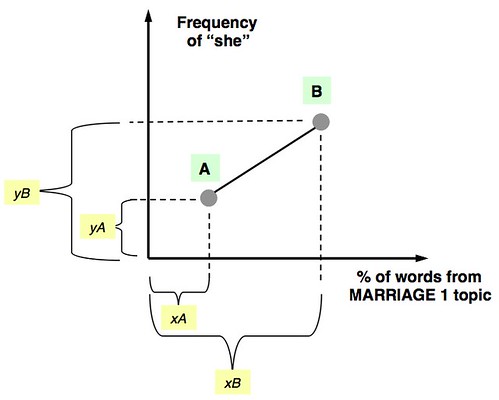

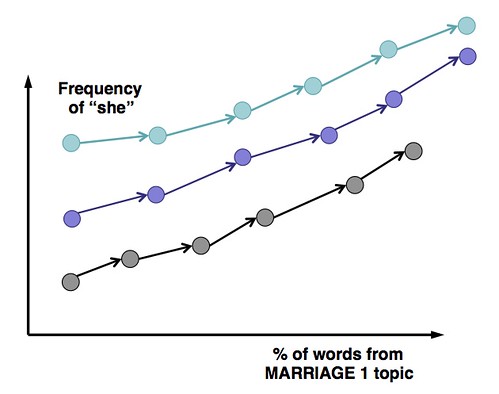

This diagram illustrates the basic idea:

The diagram shows a two-dimensional feature space in which a text’s value on the MARRIAGE 1 trait (the percentage of words taken from that topic) is indicated along the X axis (horizontally) and its value on the stylistic trait, the frequency of “she”, is indicated along the Y axis. I’ve indicated the positions of two imaginary texts, A and B, in this space.

We can calculate the (Euclidean) distance between those texts using this formula:

That distance is a measure of how similar the texts are with respect to those features. The distance between highly similar texts will be short, while that between dissimilar texts will be long.

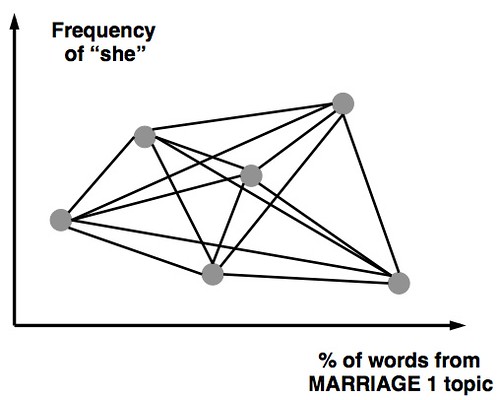

In the following graph we have six texts charted:

As in the first case, the edges (lines) between the texts (nodes) are proportional to the distance between the texts in this two-dimensional feature space.

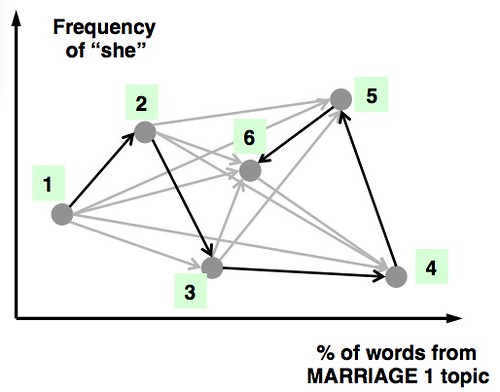

The next graph is pretty much the same except that I’ve put arrowheads on all the edges. The text at the tail end of the arrow was written before the one at the head end. I’ve also rendered a selected few of the edges in black and the rest of them in light gray. Notice that all black edges point in the same direction, making it unidirectional chain.

One could pick out many similarity chains in this graph, but I’ve chosen the only one that includes each node.

The layout of this chain makes it obvious that these imaginary texts do not line up in temporal order from left to right. We see that texts five and six are between texts three and four in left to right order. The most recent text, six, is roughly the same distance from two and three as it is from its immediate predecessor, five, and closer to them than it is to four.

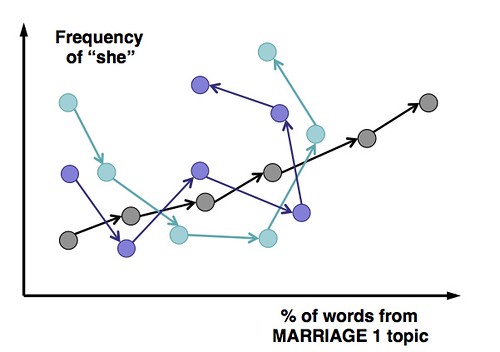

Now consider this diagram in which we have three unidirectional chains, each involving six texts (for sake of diagrammatic clarity, I’ve not indicated any non-chain edges):

Two of the chains, the blue and the green, are like the one in the previous graph in that they don’t line up in temporal order from left to right. The third chain, in black, does line up in temporal order from left to right.

But what if all of the chains lined up in temporal order from left to right?

That, in effect, is what happened when Jockers performed his analysis. I say “in effect” because Jockers did not examine individual unidirectional chains in his graph, nor have I done so myself. But the result that he got, which we’ll examine in a minute, implies that that’s what happened.

That requires an explanation. In fact, it requires two explanations. We need one account to explain what’s going that a given unidirectional chains chart as a diagonals in the feature space. That implies that the measured traits are not independent of one another; rather, they are highly correlated. We need another account to explain why most, though perhaps not all, of the unidirectional chains are of this type.

The first account is about the internal construction of novels in its relation to change. The second account is about how novels function and circulate in society.

With this in mind, let’s now look at what Jockers did.

The 19th Century Anglophone Novel

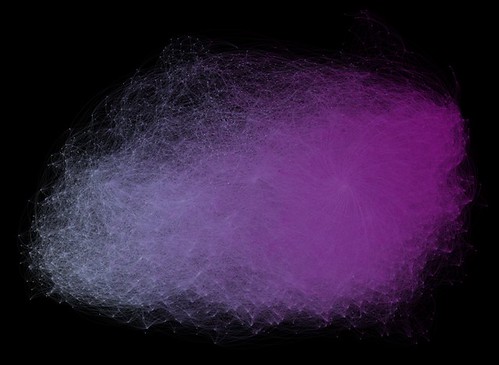

Jockers took most, though not all, of his 500 thematic features, and most of his stylistic feature, and combined them into a single model with 578 features for each of the 3346 texts in his corpus. He then calculated the pair-wise similarity of all the texts and tossed out all values below a certain relatively high threshold (pp. 162 ff.). The result is a graph having 3346 nodes and 165,770 edges embedded in a space with 578 dimensions, one for each feature. As in the examples in the previous section, each text is represented as a node in the network and the similarity between two texts is represented by the edge (or link) connecting them. The length of the edge is proportional to the degree of similarity.

In principle it is the same kind of mathematical object as those we examined in the previous section. But how do you visualize such a huge graph? YOU don’t. You get a computer to do it. One of the things the software does is project those 578 dimensions onto two dimensions so that we can create a visual representation. Here’s that representation (Figure 9.3 in the book, p. 165, color version from the web):

The visualization routine (Force Atlas 2 in the Gephi package) is designed to layout the graph so that similar texts are close together. As in our simplified example, there was no temporal information in the data from which that graph was derived. As a side effect of that process, however, the graph is also laid out more or less (there are a few outliers that are out of order, p. 167) in temporal order, going from older to newer, left to right. It should be obvious that Jockers would not have gotten this result if the unidirectional chains in his graph were not themselves physically ordered from left to right in feature space.

Here is Jockers’ comment on this result (pp. 164-65):

The fact that they line up in a chronological manner is incidental, but rather extraordinary. The chronological alignment reveals that thematic and stylistic change does occur over time. The themes that writers employ and the high-frequency function words they use to build the frameworks for their themes are nearly, but not always, tethered in time. At this macro scale, style and theme are observed to evolve chronologically, and most books and authors in this network cluster into communities with their chronological peers.

On Jockers’ first sentence, it is neither incidental nor extraordinary IF an evolutionary process regulates cultural change. For evolution proceeds through “descent with modification,” as Darwin put it, and that goes for cultural as well as biological evolution. If a later individual is modified from its immediate predecessors, it will in fact resemble them a great deal; the modifications do not change the basic character of the descendants.

We must further realize that Jockers’ graph in effect represents a collective mentality. Jockers wasn’t examining the minds of millions of 19th century readers of English-language novels in Britain and America, but the history of those novels is a function of the tastes and interests of those readers. Those books wouldn’t have been written if publishers didn’t think they could see them to the public. Those tastes changed gradually, with the themes and styles of novels appealing to those tastes changing gradually as well.

Why Did Jockers Get That Result?

Let’s return to two questions we posed earlier: 1) why do unidirectional chains chart as diagonals in feature space, and 2) does change appear to be coordinated across all chains? I don’t have really good answers for these questions, but I do have some thoughts.

Let us start with the second question, which seems easier to me. These novels are not written each in its own encapsulated mini-society. They are shared among groups within the larger society, ultimately in this case, the English-speaking world of America, Britain, Ireland, and Scotland in the 19th century. Literary texts are a means, though not the only one, by which people share their values, desires, attitudes, and aspirations (see, for example, my post Seven Sacred Words: An Open Letter to Steven Pinker).

As such, the texts that circulate in a given group will draw on the same set of values and concerns. As the group changes over time its values and concerns may change as well, but in a fairly concerted fashion. In this process some popular genres may no longer seem compelling because they do not easily encompass newer concerns. By the same token, formerly obscure genres may more readily express newer concerns and so texts in those genres will proliferate at the expense of texts in older genres (recall Jockers’ Table 6.5, reproduced above).

On the first question, forgetting about temporal order for a moment, diagonal chains in feature space indicate that that the features of that space are interdependent. Variations in feature values are correlated with one another. One conception of literary texts, that they are “organic wholes” implies that their traits are highly correlated. And whether or not one is a student of organic wholism, it is obvious that many traits are correlated with one another.

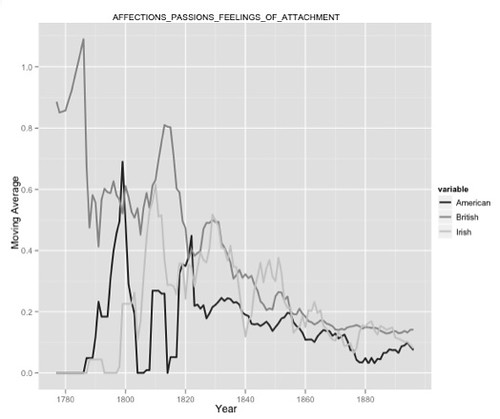

For example, this theme, AFFECTIONS PASSIONS FEELINGS OF ATTACHMENT, shows a temporal course that is similar to that of MARRIAGE 1, a decline through the 19th Century:

The designator Jockers gave to it tells us why; novels about marriage are also likely to involve affections, passions, and feelings of attachment. We expect some kind of coherence and interdependence among the various elements that constitute a literary text, however those elements are identified.

No, what’s interesting is the fact that changes in patterns of textual coherence have a consistent temporal direction. Why doesn’t the pattern of similarity among successive ‘generations’ circle back on itself or just meander about in feature space? It would appear that, contrary to conventional wisdom, there is something like progress in literary culture. But “progress” is just a word. Using it in this context doesn’t explain anything, though it does point up the issue.

The traditional way of accounting for directionality, of course, is through teleology. That would imply that the 19th Century novel is evolving toward something. The 20th Century novel, perhaps? And what’s that evolving toward? No, biological evolution dispensed with teleological thinking and it should be banned from cultural evolution as well. Whatever the novel is doing as it evolves, it isn’t seeking something in the future. It’s seeking something in the present. What?

As much as I like to meander around and about on that question I’m going to leave it alone. I think it’s a matter for a generation or two of serious investigation.

What Remains to be Done?

Everything, mostly. For one thing, we need an explicit model in which the cultural correlates to genes, phenotypes, and species are identified, for those are the central (theoretical) actors in biological evolution. A great deal has been written on this issue in the past two decades, though, alas, most of the work written under the rubric of memetics is somewhere between questionable and worthless. I’ve worked on these issues a great deal, but will not attempt to summarize that work here, though I’ll list some of it at the end of this essay.

I note, however, that such a model has to work on several scales, as does biological evolution. At the macroscale we have the long-term evolution of literary culture; that’s what Jockers has investigated. At the mesoscale we have the detailed study of individual literary works; there is where we investigated the interdependence of the elements constituting works of literary art. At the microscale we have the inner mechanisms of language, feeling, and desire, the bricks and mortar of literary cathedrals.

Of course, the student of literary evolution doesn’t have to undertake any of that work from scratch. There is a great deal of excellent work from which to start. But recasting that work in new terms is likely to be difficult, not to say controversial. And there will be much new work to do. I would expect the emerging disciplines of digital criticism to take the lead in this effort, for, as I said at the beginning of this essay, they are the only ones providing us with new conceptual objects.

Will the profession allow them to thrive?

Appendix: In Search of Models for Cultural Evolution

I’ve done quite a bit of work on Jockers’ Macroanalysis which I gathered into a single working paper: Reading Macroanalysis: Notes on the Evolution of Nineteenth Century Anglo-American Literary Culture. I gave considerable attention to Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel in those notes.

Earlier in my career I did quite a bit of work on the notion of cultural complexity; much of that work was done in conjunction with David Hays. That work is not, for the most part, directly relevant to the current discussion, but you can find it at a website: Mind-Culture Coevolution: Major Transitions in the Development of Human Culture and Society.

The lines of investigation in my book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil: Music in Mind and Culture (Basic Books 2001) are more directly relevant to this essay. In the second and third chapters I undertook to conceptualize the music-making group as a neural entity. The upshot is that, when members of a group are interacting under in a certain way, their nervous systems become coupled into a single dynamical system. You can download final drafts of those chapters HERE. I discuss gene-like and phenotype-like entities on pp. 191-194 and 219-221.

I’ve got two working papers in which I discuss gene-like entities, aka memes, in some considerable detail. The popular notion of memes as autonomous bots of some kind is intellectually empty. These two papers explain why and present a coherent alternative:

- The Evolution of Human Culture: Some Notes Prepared for the National Humanities Center, Version 2 (http://ssrn.com/abstract=1631428)

- Cultural Evolution, Memes, and the Trouble with Dan Dennett (http://ssrn.com/abstract=2307023)

In the terms I develop in that second paper, the function words Jockers uses in stylistic work would be connectors and the contents words in thematic work would be designators.

Finally, we have Cultural Evolution: A Vehicle for Cooperative Interaction between the Sciences and the Humanities (http://ssrn.com/abstract=1644978):

The study of cultural evolution requires a comprehensive approach to les sciences de l’homme using methods and insights from researchers trained in both the humanities and the sciences. Only humanists have the wide-ranging knowledge of cultural phenomena necessary for effective analytic and descriptive control of the primary phenomena; without such control model building and theory testing are pointless. Scientists, on the other hand, are beginning develop tools for thinking about population-wide maintenance, propagation, and incremental change of cultural codes. At the micro-scale we need to understand, not only perceptual and cognitive processes, but, most critically, the negotiation of meaning through interaction. At the macro-scale we need to see how changes in cultural codes supports the emergence of new mentalities. Taken in sum these efforts will show us how the design of cultural codes emerges from the collective efforts of populations where each individual negotiates his or her life transaction by transaction.

* * * * *

Bill Benzon blogs at New Savanna.