by Andrea Scrima

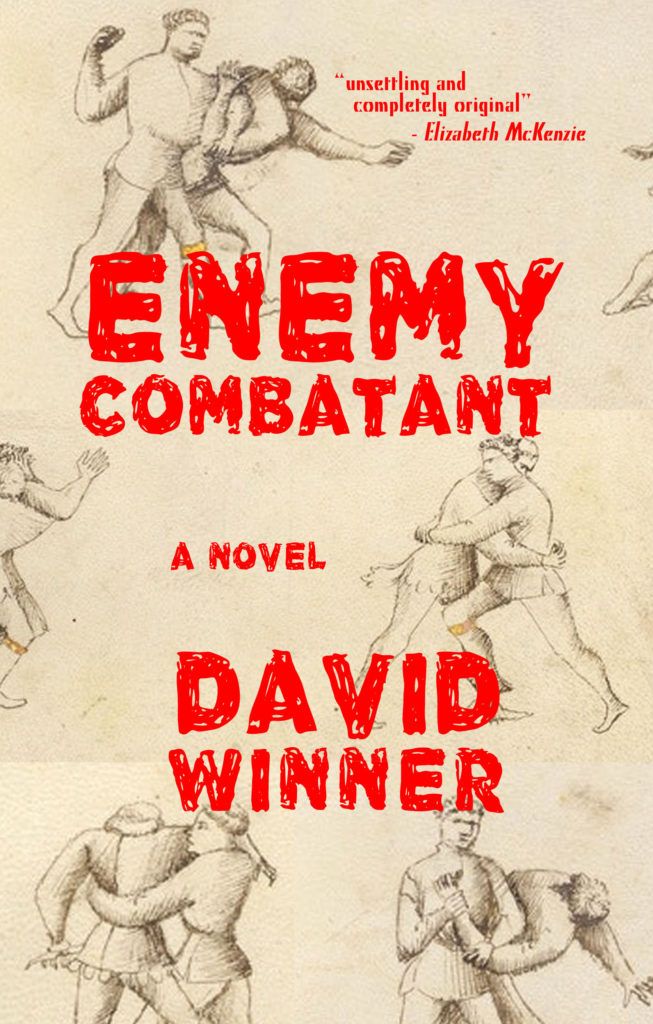

David Winner’s third novel, Enemy Combatant, has just been published by Outpost19 Books and has already received a starred Kirkus review. The book is an action-packed road trip gone horribly haywire, a misadventure mired in alcoholic debauchery and doomscrolling-induced moral indignation at the imperial arrogance of the Bush administration following 9/11. Sensitively and intelligently written, it wobbles between the tragic, comic, and utterly ridiculous as two close friends set out to free someone, anyone, from one of the extra-judicial black-op sites the US set up in the Caucasus and elsewhere and document the evidence. I spoke to David about some of the ideas behind his tragicomic page-turner.

Andrea Scrima: Your new novel, Enemy Combatant, looks back to the Bush era from a point in time still buckling under the enormous pressure of the Trump administration. Before the book even gets underway, we’re given a comparison between these two periods in recent American history: the stolen election of 2000, September 11 and the wars that followed, the reintroduction of enhanced interrogation and torture and, of course, the black-op sites you home in on in your novel—as opposed to kids in cages, half a million Covid deaths, withdrawing from the Paris Treaty and everything else the past administration was infamous for. Looking back over the past 20 years, what similarities do you see between these two periods, and what are the key differences?

David Winner: I don’t like using “neo-liberal” because it’s such a bogeyman term, but it comes in handy while describing the Bush years. There was a hawkish consensus in the United States, a thirst for blood, stemming from 9/11. It’s hard to separate Bush from both Clintons and Tony Blair as they, along with the “reliably liberal” New York Times and The New Yorker, all supported the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, which turned out to be a slippery slope to torture. Like the protagonist of Enemy Combatant, I was infuriated by the Bush administration, a fury that was aggravated by the sense of being part of a small minority whose conventional left-wing belief in the flawed history of American foreign policy didn’t get flipped around when the towers came down.

Obviously, the outrages of the Trump administration, concluding with January 6, would be almost hilariously extreme if the death and injury toll were not so extensive. But under Trump, everyone surrounding me was so outraged that it didn’t feel so incumbent upon me to be outraged myself. I was also older and, dare I say it, a bit saner than I was during the Bush years, though I can’t put blame my unhinged reaction to Bush on youthful indiscretion because I was already in my thirties.

To try to better answer the question, Trump’s America-first isolationism, born of the worse cynical instincts, meant we weren’t getting into direct conflicts. If he’d been openly hawkish at the same time, with the nuclear button in his hand, we might not be around to do interviews about novels.

Andrea Scrima: You portray one of your protagonists, Peter, as a person so porous to the violence being done to innocent people as to be damaged, nearly incapable of living his life in any effective way. His wife has asked for a trial separation; as the book begins, he and his college buddy are on a kamikaze mission, a reckless, alcohol-fueled adventure he’s not sure he’ll emerge alive from.

For me, personally, it brings back memories from that time: waiting for the bombs to drop on Baghdad, knowing that suffering and death were about to be unleashed on the populace. This came after weeks of demonstrations, when millions of people all over the world protested against the impending war—and it still wasn’t enough to keep them from invading Iraq. It was the moment when even the densest among us must have realized that we weren’t living in a functioning democracy. I’m not sure that the pain I felt over the separation of parents and children at the southern US border ever reached quite that pitch, which I still remember so well. Have we become numb since that time? And what does that mean for us as a country?

David Winner: I think the key words in your question are “around the world” when you describe demonstrations against the Iraq War. I remember reading about the protests in Germany and the truly massive one in London that made its way into a novel by Iraq War-apologist and Tony Blair-buddy Ian McEwan. If we were to consider that it was primarily an American War, we might have expected even vaster protests in America, but that didn’t happen. While there were indeed large ones—I remember carrying a very awkward faux coffin with a friend during one in New York—they were not at all of the scale of the Vietnam ones. The war was actually quite popular, at least in its early days, despite how illogical the whole thing was. We think of the insane and evil stupidity of believing in election fraud without evidence, but even though Iraq had nothing to do with 9/11 and didn’t have weapons of mass destruction, many Americans supported invading it. I say all this as a way of answering your question about numbness. For me, during the Bush II years, similar to my protagonist in Enemy Combatant, I was driven nearly insane by the sense that many surrounding me couldn’t see what was right in front of their eyes.

But I think the basic psychology of desensitization may account for both of our numbness. We all know the studies that show that people will donate tons of money if they see a poignant photo of a starving child, but a scene of dozens of them will overwhelm them and turn them off. How could we be anything other than desensitized with the Trump insanities exploding all around us day after day for four years of our lives? In Germany, you could maybe better hide from that face and that voice. As for the country, I think there is a kind of a universal PTSD. Trump supporters can’t get over his defeat, and the rest of us can believe we have our country back, sort of, and fear it will slip away from us again.

Andrea Scrima: But there’s nowhere to hide: I was as glued to the news these past four years as if I were living in New York, and I was just as glued to the news twenty years ago. While I was reading Enemy Combatant, I found myself relating to Peter, to his rage and confusion and misdirected attempts at “doing something.” But Sarah, his logically-minded wife, sees Peter’s suffering as a case of paranoia requiring psychiatric treatment. Peter is determined to find the black detention sites in Armenia and Georgia whose existence chance rumors alerted him to; he wants to record them on his phone—the cages, the beaten-down prisoners, the guards, the bullet-proof vehicles, the dilapidated sites of clandestine torture chambers where the US government outsourced its dirty work—proof to justify his outrage and desperation, proof for Sarah, whom he is terrified of losing. But when Peter’s mother dies unexpectedly from a surgeon’s error, he loses it and begins perceiving the world in religious terms; he begins to see signs in the things around him, see himself on a holy mission. The theme of American paranoia brings DeLillo to mind: paranoia as the only reasonable state of mind in a dangerous world, the only sane approach to the unending proliferation of lies and conspiracies. Where does American paranoia fit in now, following the storm on the Capitol? Or have we moved into something new, something we haven’t yet understood?

David Winner: My grandmother grew up Catholic in Prague (I’ve seen her Austro-Hungarian citizenship papers) but after she came to the United States in the early twenties, she and my grandfather gave up their religion for reasons we’ve never figured out. But when she was dying in the nineties, apparently, she recited the “Hail Mary” in Czech again and again. Peter’s Polish Catholic mother’s turn towards religion on her deathbed does leave Peter looking for some sort of spiritual direction. I didn’t quite see it as a holy mission, though I wish I did because I love that as an idea. Certainly, his extreme beliefs and actions are influenced by some confused notion of faith and the loss of a loved one. As for DeLillo, paranoia, and the Capitol, I tend to think that we (meaning decent folks living in at least semi-reality) need to win paranoia back from the Loony Tunes. Up until recent times, we (that same we) were rightfully paranoid about, for example, a CIA that secretly engineered coup after assassination after coup and set up secret torture prisons, but more recently the CIA and FBI, the so-called “deep state,” have become one of our only bastions against the absolute unrealities of election fraud, Democratic Party Satan worshiping, and everything else that those who attacked the Capitol believed. The obvious fear is that our new-found respect for federal agencies will bite us in the ass, especially as the Iraq War-supporting Biden tries to reengage with the world. Plenty of reason for paranoia of the more existential DeLillo variety and also the real. What can we trust or believe after all of this?

David Winner: My grandmother grew up Catholic in Prague (I’ve seen her Austro-Hungarian citizenship papers) but after she came to the United States in the early twenties, she and my grandfather gave up their religion for reasons we’ve never figured out. But when she was dying in the nineties, apparently, she recited the “Hail Mary” in Czech again and again. Peter’s Polish Catholic mother’s turn towards religion on her deathbed does leave Peter looking for some sort of spiritual direction. I didn’t quite see it as a holy mission, though I wish I did because I love that as an idea. Certainly, his extreme beliefs and actions are influenced by some confused notion of faith and the loss of a loved one. As for DeLillo, paranoia, and the Capitol, I tend to think that we (meaning decent folks living in at least semi-reality) need to win paranoia back from the Loony Tunes. Up until recent times, we (that same we) were rightfully paranoid about, for example, a CIA that secretly engineered coup after assassination after coup and set up secret torture prisons, but more recently the CIA and FBI, the so-called “deep state,” have become one of our only bastions against the absolute unrealities of election fraud, Democratic Party Satan worshiping, and everything else that those who attacked the Capitol believed. The obvious fear is that our new-found respect for federal agencies will bite us in the ass, especially as the Iraq War-supporting Biden tries to reengage with the world. Plenty of reason for paranoia of the more existential DeLillo variety and also the real. What can we trust or believe after all of this?

Andrea Scrima: Leonard, Peter’s friend and comrade in arms, is wrathful, self-destructive, and extreme, and he reads almost more as a symbol, a homegrown avenging monster of the American subconscious. At the same time, he is the more ingenious of the two—in a dangerous situation, his mind focuses sharply, becomes resourceful. Is it an overinterpretation to say that while Leonard represents Peter’s worst side, he is also, in a sense, Peter’s survival?

David Winner: A friend who was adopted (mother from Korea, father a US serviceman of Mexican descent) has read this book and my last one, both featuring (weirdly!) characters such as Leonard who were Korean adoptees. Quite reasonably, she asked me why I did that, which made me better articulate it for myself. I think the first thing about Leonard that I had in mind is that he is so unbalanced and extreme partially because he was born so out of culture as his unsympathetic, not very loving parents had zero interest in his Korean origin. He (very ingenious, yes) is unbelievably impulsive in part as a result of not really coming from any kind of stable place. I didn’t see him as an American symbol, but I like that idea. I tried to create in Peter an at least somewhat sympathetic and believable character, who behaves in an insanely reckless and ill-thought-out matter. Having another character even more off-balance kind of egging him on is part of that. I was also harkening back to the male comedy duos of old: Laurel and Hardy, Abbot and Costello. I didn’t have them meet the mummy or Frankenstein or join the French Foreign Legion but landed them in a truly dark place, implying the troubling implications of lots of buddy movies. Peter, unbelievably, is sort of the straight man in that formulation.

Andrea Scrima: Not only do they wind up in a dangerous situation, they also get a pretty good look at the more sinister parts of their own psyches. Meanwhile, the road from the Tbilisi airport is called “President George W. Bush Avenue,” an odd detail in a part of the world most Americans didn’t give much thought to at the beginning of the new millennium. How much research went into the writing of Enemy Combatant, and did you travel the roads you describe so vividly?

David Winner: As anyone who has ever spent time writing fiction remotely connected to their experiences has probably experienced, we can easily confuse our memories and our inventions. My memory is that the Tbilisi airport was named after Bush II. Looking up the road reveals that to be true, but I would not have been surprised if it were not.

I did visit most of the places in the novel: one trip to Georgia and the Lori Valley of Armenia around 2012, when I had been spending time with my wife in Turkey, and a novel-research trip back to Armenia about a year later when I went to the Turkish border where some of the action of the novel takes place. Actually, witnessing the small border fence and Russian-run border towers did have a lot of influence on the novel.

The Armenian driver who took me to the border without asking me why I wanted to go (thankfully I think I was too messy-looking to seem CIA) also took me to an isolated place right near the border. where there was a weathered illegible tourist information sign. He handed me binoculars and had me gaze over the border. Eventually, I saw the ruins of Ani, the ancient Armenian capital, glimmering in the distance. It lay in Turkey, out of reach of most Armenians as the border was closed and the journey through Georgia both long and expensive.

While writing the novel, I both was and was not interested in accuracy as I wanted the story to have an absurdist mythical quality but to be believable enough to grab readers at the same time. Maybe a tall order. I don’t know where I got the idea of placing a dark-op site in a copper smelter (which I did visit) in Armenia. Abandoned industry as a kind of picturesque gothic has almost become a cliché. I wasn’t trying to create a real CIA secret prison, and I’m sure no stupid young American could ever penetrate an actual one, but I did occasionally check where those prisons were rumored to be. That information kept switching: Poland, Romania, Macedonia. Then, finally, when I was well into working on the novel, I saw that Georgia and Armenia had been added to the list. My hyperbolic imagination may have somehow landed upon something all too real.

Andrea Scrima: David, the term “enemy combatant” is a label invented to circumvent the Geneva Convention—can you talk a bit about choosing this as your title?

David Winner: Well, I think I had two basic things in mind: one satiric, the other serious. The term “enemy combatant,” a Geneva Convention work-around as you point out, implies someone tough, dark, intimidating, which is pretty much the opposite of how Peter would present if you were to meet him. The thought of him fitting that designation was supposed to be little bit funny. On the other hand, it is such a lethal accusation, like a diagnosis of a terminal condition. Most so-called “enemy combatants” caught during the Bush years, we can reasonably speculate, are either dead or deadened from the abuse they suffered. Recent interviews with Guantanamo detainees reveal many of them to be very normal, maybe kind of nerdish men in the wrong place at the wrong time. Of course, there are people out there, the legendary Iraq War sniper, Chris Kyle, for example, who truly seem like the kind of killing machine that the term “enemy combatant” might suggest. But he didn’t get called that because he was on “our” side. I think I was trying to interrogate or deconstruct a really insidious bit of American terminology.

Andrea Scrima: For your British Pakistani character Humad, the term “enemy combatant” is ineradicable, like a tattoo; eventually, like all undeserved labels, it becomes prophetic, a self-fulfilling prophecy. Thanks, David, for taking the time out to have this conversation with me.

David Winner is the author of Tyler’s Last and The Cannibal of Guadalajara. His work has appeared in The Village Voice, The Kenyon Review, The Iowa Review, The Millions, and other publications in the US and the UK. He is the fiction editor of the Rome-based magazine, The American, a contributing editor for Statorec, and a regular contributor to the The Brooklyn Rail.