by Xavier Muller

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer with an estimate of more than 150,000 new cases in 2024 in the United States (1, 2). In approximately one third of patients, colorectal cancer is metastatic at the time of diagnosis, meaning that cancer cells have already spread from the colon or rectum to other organs in the body (2). One of the most frequent metastatic sites of colorectal cancer is the liver (50% of patients). In case the metastases are localized only in the liver, the optimal treatment is to remove them surgically in combination with chemotherapy (3). Of note, resection of liver metastases is only beneficial if all macroscopically visible lesions can be removed. Unfortunately, a complete resection of liver metastases is only possible in up to 35% of patients, owing to anatomical limits imposed upon the surgeon (3).

What are the limits of liver surgery?

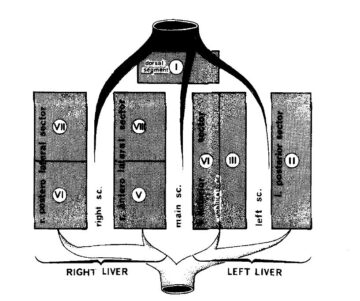

In order to understand the limits of surgical resection of liver metastases, one has to focus on liver anatomy. French anatomist Claude Couinaud published the first complete description of the functional anatomy of the liver in 1957 (4). The liver consists of two functional entities, the left and the right hemiliver, which are both supplied by three main structures: a vein, an artery and a bile duct (5). These three structures are referred to as the portal pedicle. There is a right portal pedicle for the right hemiliver and a left portal pedicle for the left hemiliver. The hemiliver can be further divided into individual segments, defined by the bifurcation of the respective portal pedicle into smaller branches (6). One can image the functional liver anatomy as a tree, with the left and right pedicles originating directly from the main trunk before further dividing into smaller branches as we approach the periphery of the tree. In total, there are eight liver segments with a dedicated portal pedicle (6).

This description of the functional anatomy of the liver has direct consequences for the surgical approach. Indeed, each segment of the liver can be removed individually by controlling its portal pedicle, hereby performing an anatomical resection of a liver segment also referred to as a segmentectomy (6). In addition, the surgeon can also resect an entire left or right hemiliver referred to as left or right hemihepatectomy by controlling and sectioning the left or right portal pedicle at its origin. In the tree analogy, one can cut off a branch in the periphery of the tree in case of a segmentectomy or cut off the major branch directly originating from the main trunk in case of a hemihepatectomy. Owing to this anatomical specificity, the surgeon can adapt the surgical resection of the liver tissue to the localization of the metastases within the liver. However, there are two major anatomical limitations which make it difficult to completely resect an important number of metastases (usually >5), spread into both the left and the right hemiliver. The first limitation is the need for sufficient liver tissue to fulfill the physiological function of the liver after resection of the tumor-loaded parts. Second, if a metastasis has invaded the main portal pedicle of both the left and right hemiliver, complete resection of the tumor is impossible since it would interrupt blood supply and bile drainage to the remnant liver tissue. In other words, if you are forced to cut off the main trunk of the tree rather than individual branches, the tree will not survive. In these two scenarios, complete resection of all metastases from the liver tissue is impossible and we speak of unresectable liver metastases. In this case, the current treatment standard is chemotherapy alone, which is associated with only a small chance of cure (3). In summary, one can say that in order to achieve cure in patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases, removing all metastases from the liver is of primary importance.

With this prerequisite in mind, another more radical approach is to remove the entire liver. This would solve the problem of the anatomical limitations of liver surgery and remove all the tumor-load from the liver. The surgical intervention allowing for a complete liver removal is liver transplantation. However, liver transplantation for patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases has historically shown poor results with a high patient mortality from early tumor recurrence (7). In addition, the fact that there are not enough donor livers available to cover the needs of the population, the transplant community has the ethical obligation to rationing. In other words, only patients with an estimated 5-year survival of >50% after liver transplantation are eligible for such a treatment (7). Available data shows that this 5-year survival rate has not been consistently reached for patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases (7). Consequently, liver transplantation has only be sporadically offered to these patients over the past decades and was not recognized as a standard treatment.

Liver transplantation as the new treatment standard?

Things have drastically changed on the 21st of September 2024 with the publication of a landmark randomized controlled trial TransMet in the renowned medical journal The Lancet by a consortium of European Liver Transplant Centers (8). The authors were able to show that the 5-year survival rate of highly selected patients undergoing liver transplantation with chemotherapy for unresectable colorectal liver metastases was significantly higher compared to chemotherapy alone. More importantly, 42% of transplanted patients were tumor free after 5 years while only one (3%) patient achieved cure after chemotherapy alone. The conclusion of this study is that liver transplantation offers a clear survival benefit with a potential for cure for patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases compared to chemotherapy alone . In addition, by reaching a 5-year survival rate well over 50%, these patients present the same life expectancy as patients transplanted for validated indications as for example cirrhosis. In the context of the rationing due to the scarcity in transplantable organs, this data justifies liver transplantation as a valid treatment option for patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases (9).

Changing the perspective

Beyond opening the door for a potential curative treatment approach for patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases, the data from the TransMet study may also change our perspective on metastatic cancer.

The potential of cure by surgical resections of a cancer, grounds on the assumption of a localized disease: a radical removal of the primary growth site of the tumor in combination with chemotherapy to avoid tumor cell spread. In contrast, in case of unresectable colorectal liver metastases, patients have a systemic disease meaning that cancer cells have already spread from their initial growth site trough the bloodstream to reach the liver, where they have formed new cancer deposits. Thus, the assumption of a localized disease is not valid in this scenario. In the TransMet study for example, patients presented with a median of 20 liver metastases at time of diagnosis (8). It is thus remarkable to see that despite this high metastatic tumor burden, radical removal of the metastatic site in combination with chemotherapy allowed to cure an already systemic cancer. The key for these encouraging results is selection prior to transplantation of patients with favorable tumor biology based on molecular signatures of the tumors, chemotherapy sensibility and evolution of the tumor over time.

These observations are the starting point of a rapidly expanding multidiscpiplinary field in medicine namely Transplant Oncology, which combines knowledge and practice from oncology, transplantation medicine and surgery (10). However, it is important to highlight that the cornerstone of Transplant Oncology is the availability of organs for transplantation. Addressing this issue is a far more challenging endeavor than conducting a randomized trial.

References

- American Cancer Society, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html, accessed on 25 November 2024

- Morris VK, Kennedy EB, Baxter NN, et al. Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(3):678-700. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.01690

- Tomlinson JS, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases defines cure.J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 4575–80.

- Couinaud C. Le foie, études anatomiques et chirurgicales. Paris: Masson; 1957.

- Bismuth H. Surgical anatomy and anatomical surgery of the liver. World J Surg. 1982;6(1):3-9. doi:10.1007/BF01656368

- Majno P, Mentha G, Toso C, Morel P, Peitgen HO, Fasel JH. Anatomy of the liver: an outline with three levels of complexity–a further step towards tailored territorial liver resections. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):654-662. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.026

- Bonney GK, Chew CA, Lodge P, et al. Liver transplantation for non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: the International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association consensus guidelines [published correction appears in Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Nov;6(11):e7. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00345-9]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(11):933-946. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00219-3

- Adam R, Piedvache C, Chiche L, et al. Liver transplantation plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in patients with permanently unresectable colorectal liver metastases (TransMet): results from a multicentre, open-label, prospective, randomised controlled trial. 2024;404(10458):1107-1118. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01595-2

- Heinemann V, Stintzing S. Liver transplantation in metastatic colorectal cancer: a new standard of care?. 2024;404(10458):1078-1079. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01926-3

- Krendl FJ, Bellotti R, Sapisochin G, et al. Transplant oncology – Current indications and strategies to advance the field [published correction appears in JHEP Rep. 2024 May 14;6(6):101071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101071]. JHEP Rep. 2023;6(2):100965. Published 2023 Nov 16. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100965

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.