by Ada Bronowski

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

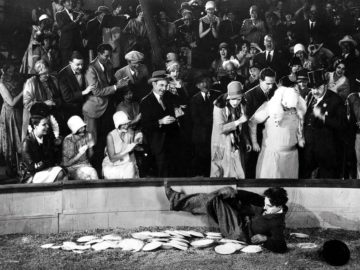

The first stand-up comedian of Western civilisation is a demure character who makes a brief appearance in book 2 of Homer’s Iliad. Thersites is ‘the ugliest man to come to Troy’, with bow-legs, sagging shoulders, a hollow chest and an egg-shaped head. He is the sort ‘who would do anything to get a laugh’. He is the Jon Stewart of the Trojan War, telling the blood- (and gold-) thirsty leaders of that insanely annihilating campaign, just that. In front of the whole assembled army, Thersites lays bare the hypocrisy of the king of kings, Agamemnon, who talks of honour, glory, and justice, but in fact does nothing but steal, hoard, rape and exploit. Thersites is immediately punished for his effrontery, beaten up by Odysseus and reduced to a miserable tear-drenched heap, the laughingstock of the army. What began in laughter ends in laughter, but the audience has switched sides.

This is a brief but famous scene. Thersites has done the rounds in the history of ideas from hero of the little people as heralded by the first modern political theorist Hugo Grotius, and as a symbol of the revolutionary spirit by Karl Marx, to makeshift populist from the Greek historian Thucydides to Nietzsche via Shakespeare who vilifies Thersites in Troilus and Cressida. In the play, Thersites’ very presence vitiates the possibility of disinterested virtues: love, justice and honour turn, under his relentlessly berating tongue, into cover-words for rotten self-interest.

The greatness of Homer, amongst other things, is to have drawn types of humanity complex enough to allow for such endless interpretations, yet also fixed enough to be forever recognisable. He did this by writing character into flesh. And if Homer’s Thersites is a fictional character, his physical determinants, the fact that that sort of character goes with that sort of body has been playing out in real life over the centuries. Only last week, at a stand-up comedy club, the New-York-based comedian Daniel Simonsen had a room booming with laughter at his own self-description as a skinny little thing, with sagging shoulders and a hollow chest. Since he remains fully clothed during the show – apart from his not being particularly tall – it is hard to verify these self-punishing descriptions. It is also unlikely Simonsen is thinking of Thersites, but of course, he does not need to.

The trope of the comedian’s frail ungainly body has been in the going for three thousand years and it has not changed. Together with truisms like ‘there is hope’, or ‘no rest for the wicked’, it is written in stone, that a comedian has sagging shoulders and is generally marked with concavities and indentations such as to mould him or her into a ‘pale omega of a withered race’ as the poet says. And it is worth noting – however much the new feminists like to make this a bane for women in particular – that men and women comedians face the same challenge: they cannot be fit and funny at the same. A comedian is a comedian the day he or she invents their own form of ideal ugliness.

As Simonsen says, comedy is the one profession for which the proficient is required to not work out. The slightly sickly, un-sculpted body is what enables a comedian to say the outrageous things they say and reap the laughs. When Simonsen muses on stage: ‘just imagine what you’d think if you saw me at the beach taking off my shirt’, we all laugh because we reach out to a shared picture book of the imagination put together through centuries of collective laughter at hollow chests and sagging shoulders. Thersites bis repetita has been reincarnating himself since Homer.

Till the laughs stop, that is. For it is that very same physical frailty which makes the punishment of the clown so easy to laugh at for the very same audience who had laughed with him but a moment ago. The switch reaction is merely the flip-side of the same coin: you laugh the first time round because you have no other way to deal with the truths you hear (on how actually horrible, or silly, or exploited or hypocritical our lives are) and you laugh the second time round because you are relieved that you are on the safe side, the side on which the masks are back on and the waters are muddied no longer. The trouble-maker, with his ridiculous body, is shut up for good. This security an audience is so quick to fall back on is guaranteed through the weightlessness of the comic body (be the comedian fat or thin). No one can take that body seriously.

Our post-war modernity began and is ending with the well-to-do from our ranks hailing and then railing two of the greatest comedic geniuses of our times. Charlie Chaplin, after having entertained the USA and the world for over forty years with the funniest and bravest films – (words will never do justice to describe the foresight, genius, depth, and, of course, hilarity of The Great Dictator made in 1940 when so many were still claiming in 1945 they did not know how bad the situation in Europe was) – was banned from even entering the country by 1952. The US authorities, in their own version of the Odysseus-treatment, transformed Chaplin into an object of derision for allegedly being a communist. Showing the plight of factory workers was funny in Modern Times (1936), but standing by the very same message the film conveyed in ‘real life’ became subversive and punishable by banishment. Some seventy years later, it is again the American elite, and its global followers, who has banished, in their own renewed Odysseus-treatment, one of the greatest film-makers of our age, Woody Allen; a comic genius, who is now barred from all ‘good’ society. It is practically impossible for him to continue working.

That frail body, whose strength comes from its weakness, allows the comedian to reach the highest feats, beyond even temerity, and with dizzying speed, sinks him to a level of rejection, beyond even rock bottom. In their genius and penetration, both Charlie Chaplin and Woody Allen foresaw their ultimate treatment: how many times does Chaplin’s character get kicked out, insulted, trampled on by the well-to-do? And as for Woody Allen, he has been fantasising, to the viewer’s great delight, about the (im)possibility of winning a fight against the fit from his very first films.

As Aristotle reports, comedians got called ‘comedians’ (in Greek: komodoi) because they were the sort of people who got banished. They were ‘sent away from the city in disgrace and doomed to roam around from one outlying village (in Greek: ‘kome’) to another’[1]. The comedian is the roaming outcast.

Marx was probably right that history repeats itself first as tragedy then as farce, but in the case of the sempiternal recurrence of the comedian, the cyclical metamorphosis should be fine-tuned: the comedian appears first as a stand-up act that ends in tragic boos and exile, to then reappear as a philosopher, a paradoxical figure of farce. Clowns are tragic: the joker, the jester, it’s a life on the edge – on the outskirts, as Aristotle says – that is made of extremes: from hilarity to abandonment, adrift on a weightless body. But their farcical reincarnation is first and foremost a creature whose flesh and blood, by contrast, weighs it down. That creature is the philosopher, whose corporeality is a continuous paradox.

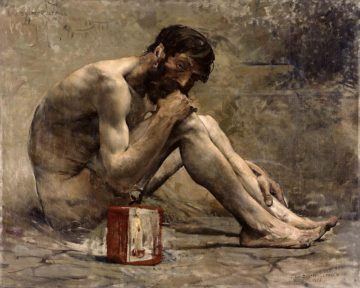

For the philosopher, who, by definition, is devoted to pure thought must at the same time, present him- or herself, on a daily basis, with and in their body – with all that that implies. From Plotinus who ‘was ashamed of being in a body’ to the 20th century French philosopher, Simone Weil, who starved herself and slept on the floor in an implacable determination to overcome the needs of the body, philosophers have had to come to terms with living the contradiction that is the cultivation of the mind in a body that won’t be silenced.

And so, after the first (ugly) comedian, came the first (ugly) philosopher, Socrates. Thersites may well be a fictional character, but Socrates is, to him, a little more than kin and a little less than fiction. Like Jesus and the dinosaurs, Socrates really did roam this earth – and not the outlying villages, but the centre of all centres that was 5th century BC Athens. The abstracted, imaginary tragedy of the comedian’s plight gave rise to the very concrete martyr of the philosopher’s body whose death, at the end of Plato’s Phaedo is so anatomically described, you can feel the heavy cold creep on you as you read how the prison-guard probes Socrates’ cold calves, reaching up his legs and thighs, and finally feeling up his benumbed belly. This is what happens when the comedian actually takes off his shirt: the cold and rigidity of death, where nothing is left to the imagination. A definition of sorts, of philosophy.

The connection between Thersites and Socrates is their physical ugliness, but there is more to it. The philosopher is always in some way laughable and makes people laugh around him when he confounds his interlocutors. Alcibiades, the handsome erst-while admirer of Socrates, says Socrates looks like a satyr, and ‘the first time you hear him talk, you burst out laughing’ (in Plato’s Symposium, 221e). Till you vote to kill him, that is. In Plato’s descriptions, as also in other texts, what at first draws laughter and even sympathy in Socrates’ demeanour, soon enough is cause for irritation and offense. That he smells, that he sometimes goes without eating or drinking or sleeping, or even sitting down – all that, ‘makes him seem superior and vain’ as the Chorus says in Aristophanes’ Clouds.

Nietzsche speaks of Socrates ‘avenging’ Thersites. United in their physical ugliness and in their rebellion against society, Socrates, for Nietzsche, is no less of a buffoon than Thersites. The Socratic vindication Nietzsche speaks of is not the kind that we find in the Marxist tradition in the wake of which a poet like Kenneth Burke goes as far as to sanctify the Iliadic renegade as ‘Saint Thersites’. Quite the opposite: it is as a nihilist that Nietzsche finds in Socrates a pioneer. He sees Socrates beginning the destruction of society from within – the society that is, which is built on the hypocrisy of noble values that no one actually upholds, just as Thersites had been saying all along. Socrates is Nietzsche’s agent of undoing. He is a caricature made flesh, (where Thersites, we may add, was a body made into an idea). Socrates systematically deregulates the mechanisms of power, of social hierarchies, of compartmentalised knowledge – he does it with a smile, and with the impunity (while it lasted) given by the etiquette of ‘philosopher’.

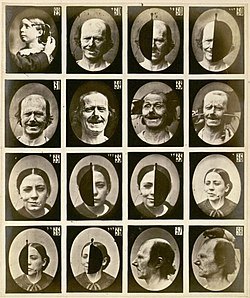

Again and again, Nietzsche belabours the legendry ugliness of Socrates: he is a monster, a cyclops. As a true follower of the French novelist Balzac, whose Human Comedy is sprawling with characters whose vicious natures are determined by their ungainly physiognomies, Nietzsche reappraises the physiognomist’s pseudo-science. It is a debate which harks back to antiquity and, not by chance, to Socrates. Zopyrus, one of the earliest known practitioners of physiognomy,  the art of telling a man’s character from his physical traits, declared on observing Socrates that he was ‘stupid, dim-witted and a womaniser’[2]. When the aforementioned Alcibiades hears the diagnosis, he bursts out laughing. But Socrates – and this is how the story was told for centuries to come – concurred with Zopyrus, all the better to attest to his will-power. It is by sheer work on himself that he overcame his bad nature. Nietzsche, however, refuses the elevated, character-building, explanation Socrates gives. For Nietzsche, Zopyrus was indeed spot on because Socrates never overcame nor countered the diagnosis. How could he? Nietzsche seems to suggest, for such ugliness, such transcendental ugliness, can only direct one’s thoughts and actions in a certain way. Falstaff cannot transform into prince Hal, whose own (princely) beauty is what makes him fit to become King.

the art of telling a man’s character from his physical traits, declared on observing Socrates that he was ‘stupid, dim-witted and a womaniser’[2]. When the aforementioned Alcibiades hears the diagnosis, he bursts out laughing. But Socrates – and this is how the story was told for centuries to come – concurred with Zopyrus, all the better to attest to his will-power. It is by sheer work on himself that he overcame his bad nature. Nietzsche, however, refuses the elevated, character-building, explanation Socrates gives. For Nietzsche, Zopyrus was indeed spot on because Socrates never overcame nor countered the diagnosis. How could he? Nietzsche seems to suggest, for such ugliness, such transcendental ugliness, can only direct one’s thoughts and actions in a certain way. Falstaff cannot transform into prince Hal, whose own (princely) beauty is what makes him fit to become King.

The epitome of Socratic ineptitude is his recourse to dialectic: ‘you choose dialectic when you have no other means’[3]. Dialectic is plebeian, vulgar. It is a kind of wrestling – the sport of the lowest of the low. But Socrates’ wrestling does not rely on the body – the deformed unfit body of the comedian-cum-philosopher. It is a wrestling for the chronically malformed, for those who cannot, who must not work out. Plato, Socrates’ student, tells us, that ‘the philosopher should not do gymnastics’, because gymnastics are ‘concerned with becoming and passing away’, that is, the growth and shrinking of muscles, objects destined for decay[4]. The philosopher must devote himself only to being. Or, as it turns out, to being and boxing – or being as boxing.

The whole development of philosophy in Athens in the 5th and 4th centuries BC emerges from reflections on the practice of wrestling. Pericles, the paragon of Golden Age Athenian virtues, the democrat, the humanist, the intellectual, used to get beaten in friendly wrestling matches by Thucydides, not the historian, but the leader of the aristocratic faction, Pericles’ political rival. But once Pericles was down, he would ‘dispute the fall, win the argument and get the spectators to change their minds about who actually won’[5].

The piquant of the situation is that in the face of brute force, a philosopher can ‘speak poignards and every word stabs’. Pericles stands here as a proto-philosophical figure. It was he who, in his breath-taking funeral oration over the Athenian dead, described the specificity of being an Athenian precisely in that Athenians are philosophers[6]. What Thucydides does with his bare hands, Pericles does with his words – and better. Just like the comedian who sends our minds gallivanting into our collective imagination, Pericles, as philosopher, carries over the match from the physical realm to the intellectual, and wins. The point being that the philosopher sublimates the body because his, is always the weaker body, but the stronger mind.

Until the spectators switch sides again, that is. Pericles’ philosophical victories did not last, and following his demise, democracy and philosophy soon became marginal once more. The aristocratic faction took back the reins, killed Socrates and Athens became a province of other tyrants’ strong-muscled empires.

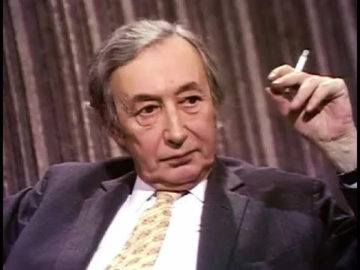

Fast-forward two thousand five hundred years, to the year 1987, at a party in the New York apartment of an underwear designer. A dainty seventy-seven year old Oxford philosopher, A.J. ‘Freddie’ Ayer, having heard some brouhaha in the bedroom, finds a man there, being violent with a woman. The philosopher feels he must intervene. ‘Do you know who the fuck I am?’, the violent man says to the philosopher, ‘I’m the heavyweight champion of the world’. As it turned out it was Mike Tyson roughing it up with Naomi Campbell. But the philosopher was not perturbed. ‘And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic’, he replied[7].

‘And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic’, he replied[7].

The fight goes on, and the story would have been perfect had Ayer got the girl. But the girl stuck with the heavyweight champion, as top-models tend to do. What is more, Tyson and Campbell were an item for some time, which rather tends to show that neither the comedian nor the philosopher can ruin the noble virtues all together: love and the games of honour to the muscle-men, truth and punishment for glimpsing it to the weaklings. The first work out, the latter can’t, it’s the rest of us that are left to work it all out.

[1] See Aristotle’s Poetics, end of chapter 3.

[2] As Cicero recounts in On Fate 10, and Tusculan Disputations, 4.37.

[3] F. Nietzsche, Twilight of Idols, II.6.

[4] Plato, Republic, 7, 521c3-7.

[5] As reported by Plutarch, Life of Pericles 8.25-27.

[6] See Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, II.37-46.

[7] Recounted in B.Rogers, A.J. Ayer: A Life, Vintage, (2000), (the authorised biography).