by Mike Bendzela

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains.

—From “Ozymandias,” Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prologue

An investigation into the livelihoods of two great-great grandfathers, both oilfield workers in Ohio, has of necessity become a study in the nature of forgetting.

I have sought one thing–my ancestral grandfathers’ involvement in the history of oil production in Northwest Ohio–only to have it slip through my fingers. In the process I have found something else, a great grandmother both besotted and besieged by the men in her life, someone whom I can scarcely look away from. With the help of my brother’s research and my mother’s endless stories, I will try to draw Blanche Thompson’s tale out of the dust of an extinct oil town.

Part One: The Oil Pumpers

The seas come and go, mountains come and go, lands come and go, and so on. What nature builds up, nature takes away. . . . [1]

While researching the various, mysterious, entangled threads of our family’s history, my brother Ben found a document–an utterly banal one, a census report–that became a rabbit hole down which my imagination would disappear.

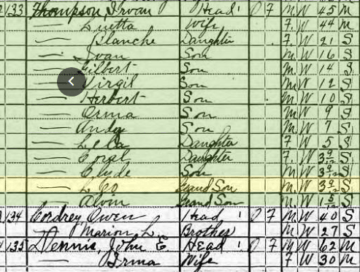

This screenshot (below) from The Fourteenth Federal Census of the United States, 1920, in Wood County, Ohio, where my great grandmother, Blanche Thompson, grew up, shows that her father, Irvan Thompson, and his wife, Luetta, raised ten children and two grandchildren, including my grandfather, Leo (highlighted in yellow), in a little house in Dowling. What caught my attention, though, was Irvan’s listed occupation, (the midsection of the document has been edited out for better visibility), shown in the upper right:

When I saw that my mother’s father’s mother’s father worked as a “Pumper” at an “Oil Field,” my immediate response was, “What ‘Oil Field’?” I’ve been to that little house in Dowling, where my great grandmother, Blanche, was raised, where she would raise her first two sons and, later, her second family, and where she would reside until her death in the 1980s. There was no oil field near there. There were no oil wells, nor idle pump jacks, nor any other signs of geology impinging on human affairs anywhere in that little settlement.

A second interesting development: Ben found another census document featuring another great, great grandfather of ours, David Goal, who also worked at an “Oil Field” in Northwest Ohio. He would turn out to be my grandfather Leo’s grandfather-in-law, after Leo married David’s granddaughter, Florence Goal. In the 1900 Federal Census of Montgomery in Wood County, Ohio, David Goal–my mother’s great grandfather–is listed as “pumper [of] oil wells.”

How was this even possible?

My ancestor David Goal did not stay in the oil industry long. He must have foreseen the fate of oil pumping in Northwest Ohio–many young workers were already fleeing to the mid-continent and Texas–so that, by the 1910 census, David and two of his sons were working in the limestone quarries of Gibsonburg, Ohio. But Gibsonburg once had mighty oil wells: “The famous Kirkbride well near Gibsonburg came in at 20,000 barrels and then averaged 7,000 barrels daily over the next month.” [2] Now they’re all dead and gone.

*

In addition to my ancestors’ jobs pumping oil, I discovered a few other ridiculously tenuous connections to the oil production history of Wood and Lucas Counties in Ohio. In 1982, having failed in my pursuit of a degree in Geology at Bowling Green State University, I transferred to the University of Toledo, within the safe zone of my hometown, to major in English. There I took a geology course for non-majors, Geology and Human Affairs, that at first was a disappointment: I had thought the “human affairs” part would mean civilizations buried by volcanoes and cities destroyed by earthquakes. But the course turned out to be a long, sobering examination of geology’s endowment to humanity: coal, oil, natural gas, and uranium, their formation, their extraction histories, their effects on the environment, and their futures. It turned out to be a class I would never forget.

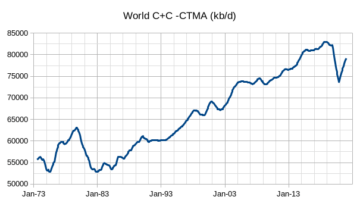

I came away thinking that by the time I turned forty (the year 2000), humanity would reach a turning point in the extraction of oil, after which–if we hadn’t changed our ways–we would be screwed. But it didn’t happen that way. I hasten to add the qualifier, yet. Everything I learned in that class about the finiteness of oil is still true.

The professor of Geology and Human Affairs, Mark J. Camp, would later “write the book” on the history of Ohio Oil and Gas. I have mulled for hours over the postcard pictures in that book, wondering how I could have grown up right on top of an extinct oilfield without even knowing it. Under our working-class neighborhood on the East Side lay the Toledo oilfield, the northern-most extent of the now-depleted Lima-Indiana field, once the largest oilfield known on Earth. Within bicycling distance of my parents’ house lay the site of the “Klondyke” oil well, the most prolific well in Lucas County, near what today can only be called an industrial wasteland, Ironville, near the confluence of the Maumee River and Lake Erie.

Ohio wells were commonly “shot,” meaning that a “torpedo” filled with nitroglycerin was lowered into the well bore, followed by a detonation charge. The ensuing explosion–call it the earliest form of “fracking”–pulverized the rock to liberate oil, gas and brine, in an uncontrolled gusher–today known as a “blowout”–which would flow for days, weeks, even months. According to Professor Camp,

The shooting of this well brought in a gusher; thus, it was given the name Klondyke. According to the crew, the well began at 5000 barrels a day, most of which flowed into the nearby creek. [3]

According to most accounts I’ve read, these early discoveries of oil and gas in Ohio, from about 1885 onward, were environmental disasters. These were the primitive days of the oil and gas industries, and engineers, geologists and machinists had to cut their teeth on these early fields. Tens of thousands of wells were driven into the rock, most of them fewer than a thousand feet deep, some as few as 50 feet, in a hit-or-miss strategy that eventually pinpointed the outlines of the mighty Lima-Indiana oilfield, the world’s first “giant” at approximately one billion (that’s one thousand million!) barrels of oil in place. After wells were “shot,” the liberated oil and/or gas and/or brine was free to spew, until the pressures stabilized. It was a monumental waste.

As described by Camp and the few other sources I could find, nearby farmers had to remove the downspouts from their houses to prevent the drizzle of sulfurous oil from fouling their water cisterns. Streams for miles around flowed with stinking petroleum, and men wore hip waders in the fields to get through the deep oily muck. Eventually, pumps could be brought in to extract the remaining thick, sour (that is, high sulfur) Lima oil to refine into kerosene for lamps, or used as lubricating oils for machinery, or bottled as “Seneka oil”, another version of the snake oil remedies rampant at the time. There was so much oil it was transferred into giant wooden and metal oil tanks–hundreds of them–which were occasionally struck by lightning, burned for days, and killed bystanders. And hauling all that nitroglycerin around in horse-drawn wagons led to multiple disasters.

While in Ohio for my father’s funeral last July, I decided to look around for the remains of that Klondyke well near my childhood home. After the well was “shot” in 1897, oil flowed continuously for two weeks. This is what the site looks like today, at Otter Creek, where all that squandered oil flowed:

*

A second connection to Ohio’s oil history: Professor Camp’s mentor, Professor Craig Bond Hatfield, taught me Historical Geology, the last course I would take toward a Geology major before I bailed to study Faulkner, Twain, Thoreau and Melville. He left an indelible impression on me, which I would later record in an interview with him I conducted for an oil depletion website in 2007. He came into the classroom every day in his pressed, white shirt and skinny tie, and drew on the chalkboard–completely in freehand and from memory–a map of North America. Then he would lecture for an hour, describing the advance and retreat of seas over the midsection of the continent, covering tens of millions of years in mere minutes.

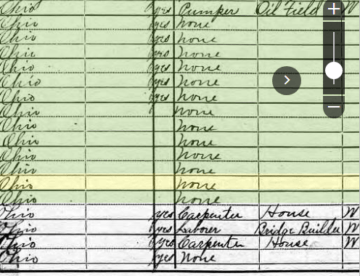

Between 1887 and 1905, the Lima Oil Field was a world-class producer, yielding 300 million barrels. . . . Lima oil lit the buildings of the 1893 World’s Fair. Production peaked in 1904, and then dropped off rapidly. By 1910, the field was regarded as virtually played out. (Source)

Professor Hatfield’s accomplishments in the field of oil depletion studies would later confirm my sense that an impending break point in history was looming, as I had learned in Geology and Human Affairs. He wrote articles for professional journals, and even Nature magazine, that asked, in clear, stark terms, “How Long Can Oil Supply Grow?”

The coming decline in [world] petroleum production rate presents an ominous economic problem with potentially catastrophic consequences. Serious and unflagging efforts to deal with this intractable difficulty are overdue.

This may seem quaint now: Hatfield published this essay in 1997, one year before his retirement, and, obviously, there has been no catastrophe. But the situation he describes has already happened to Ohio. It happened there a long time ago, in fact. But Ohio had the rest of the United States to rely on after its oilfields gave out. In fact, early oil workers couldn’t wait to get out of Ohio after the Spindletop discovery in Texas in 1901. Texas’s light, sweet crude oil flowed orders of magnitude more abundantly than the thick, sour oil of Ohio’s Trenton formation. And so, when the Lima-Indiana oil field collapsed, no one noticed, as all eyes had turned west, and the Ohio boomtowns went bust . . . Leaving me with nothing to find after I learned that I had great, great grandfathers who worked as “oil pumpers” in Northwest Ohio.

Does anyone really believe that world oil production will not ultimately go the way of Ohio? That the mighty Saudi Ghawar field will not decline as surely as the Lima-Indiana field that my grandfathers pumped? That the tight source rocks of the Permian formation in Texas will not one day fail to yield, as the Trenton limestone failed over one hundred years ago? I discovered that not many people actually care.

Sadly, it seems we humans discount the future as readily as we forget the past.

The fate of Northwest Ohio’s oilfields reminds me of the famous story about the Greek historian Xenophon’s alleged discovery of the ruins of Nineveh, the capital of the ancient Neo-Assyrian empire and once the largest city in the world. In Anabasis, Xenophon describes a harrowing retreat up the Tigris River with a group of Greek mercenaries called the Ten Thousand. They have a Persian cavalry pursuing them, and as they flee Babylonia, they come upon a great ruin:

[T]hey marched . . . to a great stronghold, deserted and lying in ruins. . . . The foundation of its wall was made of polished stone full of shells, and was fifty feet in breadth and fifty in height. Upon this foundation was built a wall of brick, fifty feet in breadth and a hundred in height; and the circuit of the wall was [twenty miles].

Xenophon actually did not know where he was. Beneath his feet lay the Nineveh of the Biblical Johah, who prophesied there; the capital of the Empire of Sennacherib, who sacked the northern Kingdom of Israel and scattered its inhabitants; and the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, with its shattered remains of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Nineveh had fallen around the year 612 BC, only a couple of centuries before Xenophon and the Greeks stumbled upon it; but as far they could see, there was nothing but piles of mud bricks. Nineveh, like the oil boom towns of Northwest Ohio, was as flat as a pancake.

I did go looking for signs of those bygone boom years in my great grandmother’s hometown. “In the eastern part of Middleton Township,” Professor Camp writes, “oil was struck near Dowling and Dunbridge in 1894. . . . The area was riddled with 57 wells in 1896.” [5] That’s my great grandmother’s stomping ground. I even visited her there as a kid, when she was in her seventies. But when I travelled back there last summer, there was nothing left to see.

*

And now that my search for the remnants of Northwest Ohio’s oil industry has failed, I have only Blanche left to talk about.

Part Two, “The Oil Pumper’s Daughter,” will appear in eight weeks, on January 16, 2023.

____________________________________

Notes

[1] Quote from Camp, Mark J. On a Handshake: Humble Beginnings to Global Impact–Ohio’s Oil & Gas Industry. San Antonio, TX: HPNbooks, 2016. Online version.

[2] Camp, Mark J. and Spencer, Jeff A. Images of America: Ohio Oil and Gas. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

[3] Camp and Spencer, Ohio Oil and Gas.

[4] Screenshot from Camp, On a Handshake.

[5] Camp, On a Handshake.

____________________________________

Photographs by the author.