by David Oates

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

Halfway through a pilgrimage, it’s a good thing to remember why you’re on it – where you hope it’s taking you. I’m following a plan to consider the strangely numerous churches of this little Portland neighborhood, just a half-mile square but crowded with varieties of religiosity.

And what is it I want? To walk towards more light. If I speak honestly, without pretended coolness . . . to breathe better, to see people more charitably. And see myself that way too. An essay is a privacy working itself into visibility. So is a walk in the neighborhood.

And so is churchgoing, where you see people in the embarrassing posture of spiritual aspiration. As if one day a week the bones of reality might show through, and prove to be something about love and justice. And possibly beauty.

Meanwhile Russians are blowing up Ukrainians on their shared Orthodox Easter. I can’t reason my way through it – it’s the human condition. So I walk and I observe, feeling for a pathway.

* * *

My wandering today finds the far corner of our “Ladd’s Addition” neighborhood, just by the light-rail platform. Busy street, crossing gates, bells (but no train-horn, thank goodness). Yet in the other direction, it’s all houses and front lawns and quiet streets.

Overlooking this corner is a surprise: the“Buddhist Daihonzan Henjyoji Temple.” But it’s closed. No signage, nothing. I’ve been noticing it for years, but it’s gone now.

It occupied a weathered, whitewashed building with pointed windows of pale colored glass. But in front, someone has built a boxy lobby right over the church windows – just their points clearing the roof of the awkward add-on.

That’s a submerged story, isn’t it: how this rather conventional little white church got handed over to Buddhists with their mysterious multisyllabic name. And who committed the architectural vandalism of that narthex?

That’s a submerged story, isn’t it: how this rather conventional little white church got handed over to Buddhists with their mysterious multisyllabic name. And who committed the architectural vandalism of that narthex?

On the web I learn that the name points to a congregation of “Shingon Buddhism,” a branch of Buddhism in Japan sometimes called “Esoteric” or “Mantrayana” Buddhism. With some digging, I add the back-story: this was the home of “St. Paul’s Lutheran Church” from at least 1898 onwards, serving a German congregation. Somehow it survived the anti-German hysterias of the war years and persisted until 1951 or ’52 (the records don’t quite agree) when the Buddhists acquired use of the building.

It’s a piquant flavor, is it not? The Germans. And then the apparently-Japanese Buddhists, who kept the steeple and the pointed windows. And maintained their own worship for these seventy years.

Later in the week comes a simple explanation: Temple still going strong. Signs taken down during remodeling. But in the moment, I feel obscurely depressed by the closed-up old church. The blankness of the entry, that ugly box made uglier by silence. Since I’m already on this far edge of the neighborhood, I decide to cross the boulevard and visit another of the adjacent churches in what I have dubbed “Greater Ladd’s.”

* * *

It seems like I’m the unbeliever always on his way to church. When I lived in Paris for a winter and a spring, for instance, I was heading twice a week (at least) to St. Eustache, a gothic-slash-renaissance marvel of a church. It was for the music, I admit – in a space of aspiration. And perhaps the best organ in Europe.

For music offers instant access to what I could call the dedicated moment. The chance, mediated through the body, to glimpse whatever is true and beautiful. Music is its own truth, isn’t it? As the Duke said: “If it sounds good, it is good.” That is, either it has weeded out the wrong turns and dead ends – has found its symmetry and surprise and excellence – or it hasn’t. To call it truth is probably a stretch, perhaps a metaphor, but to call it good is certainly right.

And so again I circle back to the question: Is beauty really truth? And is it therefore, too, a form of grace, liberating us from error and darkness? Certainly music places us in the posture of both gratitude and receptiveness. A good mentality for letting go of error and pique and other impediments.

Music at least the fore-chamber of truth, then. Offering a clear and exalted mind. A readiness for actuality.

Einstein on his fiddle. What was going on in the back of his mind while he played?

* * *

As I work on this essay it has become April, under changeable weathers. Growly dark-bottomed clouds over there, blue sky elsewhere, sun getting brighter every day. The elms have begun to leaf out, and at mid-day they give me ten minutes of treelight.

Treelight. That’s what I decide to call it. A fresh green sky just fifteen feet overhead. An almost underwater light, clear yet forgiving. The dappled sidewalk and street, its pattern moving, shifting. Certain bits lensed to sharpness through the wee gaps and apertures between leaves. A good place to hold still and be dappled yourself.

Treelight. That’s what I decide to call it. A fresh green sky just fifteen feet overhead. An almost underwater light, clear yet forgiving. The dappled sidewalk and street, its pattern moving, shifting. Certain bits lensed to sharpness through the wee gaps and apertures between leaves. A good place to hold still and be dappled yourself.

All my life this kind of moment has given me pleasure. And a feeling – not quite unconscious – that all is not yet lost.

William Blake wrote about such moments. Seeing something early in the morning – a lark ascending. Hearing those notes. Smelling the fresh thyme. He says it’s the moment in each day that Satan and “his Watch Fiends” can never find and cannot steal from us. Heaven on earth. Briefly.

A smart human would take note of those moments. Would make sure to find one of them, every day.

* * *

From a block away you can see its gray stone, built up into a compact though vertical structure surmounted by two silvery domes with crosses. From the first glimpse I knew what those domes meant – they speak unmistakably of the eastern orthodox tradition.

Yet the sign posted by its gilded, gated entrance reads: “Vietnamese Christian Community Church.” Here comes another history lesson, another sampling of the endless shape-shifting of human affairs – be they never so divine.

I went inside once when there was some event just concluded, and saw the merely whitewashed walls. Perhaps drywall, plain. None of the domed, mosaic pomp of the eastern tradition. The current congregation is Assembly of God – i.e. “Pentecostal.” All their elaboration is in the spirit, in the (to me) rather alarming whoop-de-do of ecstatic utterance, revelations, healings. Dancing, perhaps, in the aisles.

So I leave them to their own devices. But another research trip to the Oregon Historical Society validates my architectural eye (if not my spiritual one): by 1910 this structure was registered as the “Hellenic Orthodox” church, later named “Holy Trinity Greek Church.” In the mid-1950s the Greek-orthodox congregation moved into a big new church in northeast Portland, and this building began its evolutions through various more standard American “gospel” incarnations, culminating in this current “Assembly of God” congregation around 1994.

So I leave them to their own devices. But another research trip to the Oregon Historical Society validates my architectural eye (if not my spiritual one): by 1910 this structure was registered as the “Hellenic Orthodox” church, later named “Holy Trinity Greek Church.” In the mid-1950s the Greek-orthodox congregation moved into a big new church in northeast Portland, and this building began its evolutions through various more standard American “gospel” incarnations, culminating in this current “Assembly of God” congregation around 1994.

What I now call, with a historian’s friendly eye-twinkle, the Vietnamese Greek-Orthodox church.

* * *

I guess I have always had a taste for religious variety. Even excess, at least once in a while.

The Sunday Los Angeles Times of my 1950s childhood always contained a few pages of church listings and advertising, mostly in dinky boxes with small type but with larger display ads too. After swapping pages of the “funny papers” with my brothers, I would often turn to the Times Religion Supplement, skimming past the Presbyterians and Episcopalians to feast on the alluring come-ons of celebrity preachers and gurus. I recall the remarkably hypnotic portrait of one “Paramahansa Yogananda,” whose unlined, almost feminine face was framed beatifically by long flowing hair. (And yes, I memorized the strange name and its spelling. Don’t know why.) It made me think of the sepia Jesus portrait adorning the kitchens and living rooms of my fellow Baptists: in His picture, too, an almost romantic invitation.

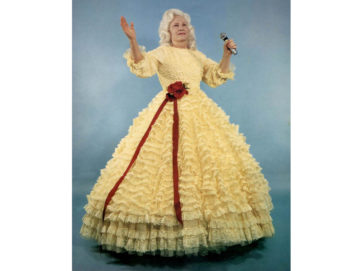

In the middle of the page there would be a BIG box advertising one “Miss Velma” and her “Universal World Church” in its somewhere-downtown building, or auditorium, or church. Miss Velma, in flowing raiment and long glamorous hair, would be promoted as RIDING A WHITE HORSE upon the stage! Or DESCENDING FROM HEAVEN ON A CRESCENT MOON! All to illustrate . . . whatever crowd-gathering angle had been cooked up by her and her co-preacher “Dr. O.L. Jaggers,” who had so many degrees they couldn’t all be listed. The preacheress herself is granted an advanced degree too, under the remarkable sobriquet “Dr. Miss Velma Jaggers.” (Why did I never realize, later in life, that I could be called “Dr. Mister David Oates”!?!)

In the middle of the page there would be a BIG box advertising one “Miss Velma” and her “Universal World Church” in its somewhere-downtown building, or auditorium, or church. Miss Velma, in flowing raiment and long glamorous hair, would be promoted as RIDING A WHITE HORSE upon the stage! Or DESCENDING FROM HEAVEN ON A CRESCENT MOON! All to illustrate . . . whatever crowd-gathering angle had been cooked up by her and her co-preacher “Dr. O.L. Jaggers,” who had so many degrees they couldn’t all be listed. The preacheress herself is granted an advanced degree too, under the remarkable sobriquet “Dr. Miss Velma Jaggers.” (Why did I never realize, later in life, that I could be called “Dr. Mister David Oates”!?!)

Sunday by Sunday I would marvel at all the unknown churches, doubting that they loved Jesus sufficiently and in the correct way (Baptists had quite strict requirements). Nonetheless I took in the dreamy eyes of Yogananda. And looked to see what that Miss Velma was up to next.

In my late twenties I dragooned some friends for a visit, in the flesh, to an actual service at Miss Velma’s old church. She was gone by then, though memorialized in history as one of the first of what we now call “televangelists.” Her church, sadly emptied of her magnetism, was captained now by a silver-haired preacher who kept up a confident and oddly disdainful mien, as if the church folk had come there to have some religious scorn hurled at them. Was it Jaggers himself? I don’t recall.

In those days people still dressed for church, and my pals and I wore our ties and navy blue suit-coats and took our seats trying not to make too rude of an interruption – though we contrasted in every way with the older, obscurely depressed congregants scattered around the auditorium. And our intent was, I’m ashamed to say, mostly satiric.

We found ourselves in what preachers like to call A Series, titled (on a big banner at the back of the stage) “Days of MAMRE.” I had read the Bible, front to back, but I didn’t remember anything like that. Apparently this guy had fetched an obscure word out of the Old Testament and based a whole series on it. The aim (clearly) being obfuscation. To impress the rubes. And separate them from their money.

Though when I looked around the scattered congregation, I could see there was very little money involved. Who knew how these souls had washed up here? I guessed they came for the show.

It was what was left of the “Universal World Church.” Online you can still see a talk or sermon of Miss Velma’s husband “Dr.” O.L. Jaggers. He’s an impressive guy, broad-shouldered, confident in voice and manner. But what he has to say is jaw-dropping, a pile-up of pseudoscientific terms into a tower of theological babble. If you know anything about the subjects he roams about in – biology, astronomy, subatomic physics – you‘ll soon pick up that he doesn’t possess even the most basic understanding. The sciency-ness provides him with impressive-sounding vocabulary – all absurdly inflated. The tape I looked at pursues the remarkable topic “Where Does God Come From,” developing God’s origin story, as Jaggers says, from “trillions and trillions of light years ago.”

Of course light years measure distance, not time. An eighth-grader with a little aptitude knows this. It’s a small example of the horseshit of this entire operation of stagecraft and spectacle. I’d like to say the thing is miscategorized under the heading of “religion.”

But is it?

* * *

On a brighter, more recent day, I find my way to the handsomest structure in the whole neighborhood, a gleamingly horizontal temple built (I later learned) in 1923. It’s a chaste design, all white, two storied, listed as “prairie style” but with wide, quietly classical architectural urns set at intervals lending it a kind of ritual glamour. Over its door, flanked by sculptures of two calmly heroic, torch-raising angels, the name carved in wood “I AM SANCTUARY.”

On a brighter, more recent day, I find my way to the handsomest structure in the whole neighborhood, a gleamingly horizontal temple built (I later learned) in 1923. It’s a chaste design, all white, two storied, listed as “prairie style” but with wide, quietly classical architectural urns set at intervals lending it a kind of ritual glamour. Over its door, flanked by sculptures of two calmly heroic, torch-raising angels, the name carved in wood “I AM SANCTUARY.”

I’ve been wondering about it for years. So it is with a little flutter that I finally enter, during a Saturday open house.

I am welcomed by three folks, all gray haired like me. We stand together on the lower “library” level as they try to convey to me the power and urgency of their esoteric revelation. The most clearly-spoken is Rick, a pleasantly vigorous fellow who doesn’t press. He offers his best answers to questions or says simply that he doesn’t know. One trusts a guy like that. He’s unsure, for instance, who the original occupants of the building were. His group, called the Saint Germain Foundation, took it over “around 1967.”

A yet older woman makes a less inspiring though wholly friendly impression. She’s very eager to impress upon me something about “vibrations.” Something, specifically, about the color purple, or maybe it’s lavender. I notice purple cloth hangings in the downstairs room. And then I notice that all three of my greeters are wearing shirts or blouses in varieties of this hue. The older woman, her voice trembling with excitement, explains that all the universe is vibration, but that purple is the most “energetic” and will heal you or direct you or perhaps it was energize you.

Rick is kind, patient. He sees that the vibrational discourse is not impressing the visitor. At my request, he provides some pamphlets offering reprints from their key works. The core message is that an “Ascended Master” known to church tradition as St. Germain has appeared to two American prophets of the nineteen thirties and left instructions to guide seekers through the reincarnations that are supposed to culminate in each of us becoming, ourselves, Ascended Masters. (The two prophets were convicted of fraud, but later exonerated by the Supreme Court on first-amendment grounds.)

Reader, I grew up in Southern California in the hippiest of hippy days. Worse, I later lived in Santa Monica, which is certainly a world hotspot for, let’s say, esoteric believings. You can’t turn around in that town without encountering a guru or a guru’s disciple. And this I know: they all are purveyors of “energy.” They all are impressed – convinced! – by the metaphor of vibration without realizing, of course, that it is but a metaphor. They usually think that “science” has thus somehow proven their doctrines. I could say a lot more but I won’t.

Unhealed by all the lavender, I make my thank yous and walk away. Later I page through the pamphlets. I’ve pictured the purplest of them. But I’ll let William James make the definitive comments.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) James explores “New Thought” (or the “Mind-cure movement”), bundling the various strands together as “The Religion of Healthy-Mindedness.” It’s a stimulating chapter, full of insight about these popular impulses arising outside the bounds of traditional churchgoing. These include the various versions and fads of positive thinking and the established churches of Religious or Christian Science – all presenting their eclectic blends of Emerson, optimism, Hinduism, magical thinking, and “spiritism,” with selective elements of science thrown in.

James suggests that many people have indeed found solace and even healing there. And that to appreciate these movements we should not make too much of their “innumerable failures and self-deceptions,” which are but normal human fallibilities.

“. . .and we can also overlook the verbiage of a good deal of the mind-cure literature, some of which is so moonstruck with optimism and so vaguely expressed that an academically trained intellect finds it almost impossible to read it at all.”

The I Am Sanctuary was originally built to house a Swedenborgian church. (It’s a whole other sleigh-ride, that.) The carved name over the door was theirs, and the new occupants have kept it.

* * *

One of the people I see on my walks is crazy. Actually I hear him long before seeing him, for he shouts as he strides along, cursing and denouncing. He bellows continuously, hardly a pause – it’s surprising his voice holds out. He’s boiling with anger. But beneath that must be pain. Psychic pain, surely. Apparently continuously.

He’s youngish, slender, dressed in filth and rags. Long shaggy hair and patchy beard. I know he’s been out here a long time – I heard him a full year ago, and more – and I always give him a wide berth, crossing streets and turning corners when I hear him coming.

If all the people in all the churches and sects and temples of America simply honored the precepts of their founders, surely suffering like this would be addressed. Surely some kind of merciful intervention, some medication, some simple housing. Surely.

* * *

I walk by the I Am Sanctuary a few days later and feel a guilty pleasure in both knowing it, and avoiding it. Next to it stands another little rose garden. April is in full progress at last, warm days intruding on the exasperating ceaselessness of Northwest rain. The elms are really leafy now. Treelight again. That other mind.

On any pilgrimage, I suppose, this paradox eventually rises up. The pilgrim travels from site to site, temple to shrine, one gilded blessing after another. But at some point the traveler might begin to notice the unexpected holiness of the spaces between. How one may sit with a rock and an ant and discover the universe: a million-year planetary rock, sitting beside you like an ordinary friend . . . and bustling on its six-legged business, the full inscrutability of life.

All the infinite questions, right there.

Whether this discovery is a problem, or its solution, is up to the pilgrim to decide.

* * *

The Chinese Baptist Church with its prominent sign sits like a badge of honor on the central roundabout of Ladd’s Addition.

The Chinese Baptist Church with its prominent sign sits like a badge of honor on the central roundabout of Ladd’s Addition.

It’s been here since 1949, when the congregation moved over the river from Portland’s “Old Town” (which contained its Chinatown) where a Chinese “mission” church had been planted in 1874 by the efforts of the downtown Baptist church, which brought a Chinese pastor from San Francisco. Old Town was a rough place, full of saloons and whorehouses. Of course immigrants lived there not necessarily by choice, but by 1860 twenty Chinese businesses had located there.

In records of the 1860s and 70s I see a complaint by the Chinese to the city government specifically about Chinese women “of bad repute” working in the district. In response the mayor advocated “either removing or heavily taxing the Chinese bawdy houses.” Portland was a new city, rapidly growing, and its cosmopolitan mix of people must have been remarkable. According to research presented in the Oregon Historical Quarterly,

“During 1869 the Chinese population in Portland almost doubled due to the May, 1868, start of construction of two railroad tracks south from the city, one on each side of the Willamette River.”

In the boom times following Portland’s 1905 “Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition,” many large homes were built in Ladd’s Addition for wealthy buyers. I admire their painted woodwork, broad verandahs, and third-story dormers. When he walks with me, my partner takes photos while I stand by searching for words. We’ve been together twenty-five years and we’re well matched in this slow and thoughtful pace.

Quite early on, this neighborhood became home to people of marginalized groups, including both Italians and Chinese. And the question I’ve been presenting to residents and librarians – so far unanswered – is to ask why Ladd’s was the exception, when so many neighborhoods throughout America in the early twentieth century placed formal prohibitions on non-White ownership or residency. Ladd’s was “quite welcoming to the Chinese” (as one Chinese long-time resident told me.) And there were enough Chinese living here by 1949 to make its church a success.

Standing on its spot on the roundabout, this church signifies one place where exclusion and racist redlining did not govern the neighborhood. (Or at least did not wholly govern it – Oregon’s record with black citizens is a different story.)

* * *

So on the first Sunday in May I did what I thought I would never again do: walked into a Baptist church service. I was welcomed immediately and warmly, though my non-Chinese-ness made me stand out. The congregation was small, no more than twenty. Almost all were folks in their gray years, like me.

The service was simple: two hymns and a sermon. Followed by communion. When I entered I was handed a tiny, sealed plastic cup of (presumably) grape juice. Really tiny – maybe two thimbles’ worth. When examined, it seemed to have a cracker the size of a thumbnail sealed into it, too.

The guest preacher, a silver-haired Anglo man, mounted the pulpit centered on a stage. Below it stood the communion table, with a white cloth and nothing else but one tiny plastic cup off to one side, its seal already peeled up.

What a practiced voice the invited preacher had! He clearly knew what he was doing. I guessed he might have been a teacher of . . . is “homiletics” the word? Preaching, anyway.

With charming efficiency he launched us into an examination of the first six verses of Psalm 1:

“Blessed is the man that walketh not in the counsel of the ungodly, nor standeth in the way of sinners . . .”

And seventy minutes later, he wrapped it up and we had communion.

Seventy minutes. I can say, both pre- and post-apostasy, that I have never before sat through an hour-and-ten-minute sermon.

I saw that this was above all a confident man. His tone, his attitude, his expositions brooked no uncertainty. God was clear to him. Virtue was clear. He was one for whom the idea of life as in any way a mystery would perhaps seldom occur. He was bluff, he was hearty. He was friendly enough, though scornful of the follies of unbelievers.

A man of certainty, in a room full of people seemingly eager to be certain too. They wrote notes as he spoke. Like Thomas Hardy’s Parson Thirdly, he had the sermon-giver’s knack of organizing things into threes. One by one these points reinforced the orderly clarity of what God demanded and offered.

I sat silent as he railed at gay marriage. As he veered against school boards. Veered again to mention women who take the counsel of the ungodly and divorce their abusive husbands. He had tried to counsel the wayward woman to stay married, he said, but she would not be saved from her folly. I heard nothing about her suffering. Only that she was wrong (and he, of course, right).

The communion that followed was hosted by three male congregants who stood next to the table with its plastic thimble of Jesus. The leader peeled, ate (or nibbled), drank. So did the congregation, though I refrained. I thought of Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans – with their long history of painting and sculpture, incense, windows, bells. Astonishing choirs and organs. Bach himself. All spoke of the flesh and to the flesh . . . about the mystery of the human spirit entangled there.

In contrast, today’s service and its staging presented the centrality of the word, its elevation above all else: the apparent conviction that salvation is a matter of correct words and correct beliefs.

It had been fifty years since I had sat in a Baptist church. Today I remembered why.

* * *

Spring rolled across us and my pilgrimage was completed.

Three days later I went across town to hear the Tallis Scholars in a resonant white-marble cathedral, their unaccompanied voices exploring works of sixteenth-century composer Antoine Brumel interwoven with those of contemporary David Lang. All of us, perhaps, were saved – but briefly: delivered into a space that felt limitless and full of potentiality.

I never did get to hear the Aramaic at St. Sharbel. Maybe some other day.