by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

Author’s Note: A version of this essay was presented at the London Arts-Based Research Conference (Dec ‘23) on the topic: “The Emergence of Soul: Jung and the Islamic World through Lecture and Art”.

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit.

The Sufis aspire to the highest conception of love and understand it to be the vital force within, a metonym for Divine essence itself, obscured by the ego and waiting to be recovered and reclaimed. Sufi poetry, in narrative, or lyric form, involves an earthly lover whose reach for the earthly beloved is not merely a romance, rather, it transcends earthly desire and reveals, as it develops, signs of Divine love, a journey that begins in the heart and involves the physical body, but culminates in the spirit.

My reading of Sufi love poetry, translated from different languages, shows that even though this tradition spans more than a millennium and includes disparate cultures, it follows the same mystic logic at its core. Whether folkloric or classical, penned or belonging strictly to the oral tradition, this genre has a discernible sensibility that likely stems from interpretations of the Quran itself.

As I explore the relationship between the earthly and Divine beloved in poetry by Persian, Arabic, Urdu or Punjabi poets, I am led to the love epics sourced from the Quran. These have been abundantly repeated, adapted, and studied, and of course yield a variety of interpretations. I approach them here in relation to the three features that I understand to be the dynamics of Sufi Poetics that integrate the earthly and Divine: An all-encompassing, merciful love as the force of deep awareness (Presence) that facilitates an appreciation of differences and contradictions (Paradox) and pours into harmonious coexistence (Pluralism)— forming a circuit that flows in and out of Divine love.

“fa inni qareeb” “I am But Near” God says in the Quran. “Fa” (indeed) added to “inni” (without doubt) creates a special emphasis. The statement is both comforting and curious. If God is so near, why do we need the double-emphasis aimed at persuasion, why the tone of earnest assurance? As I understand it, this phrase is an invitation for mystic search. God, the omnipresent, is close, but is also, paradoxically, a “hidden treasure” according to the well-known Hadith Qudsi (a Prophetic saying in which God refers to himself in the first person). God is the only reality amidst a temporal and spatial panorama made of illusion that seems to easily pass for reality, even by those who have a well-developed perception. God is indeed near, but He promises no access, only the signs. He is not revealed without effort. The effort lies in decoding the signs.

The Qur’anic verse or “Ayat” is translated as “sign.” The surface meaning of things is not only insufficient, but it can also be misleading. The Quran is a language of symbols that explains itself fully only to those who have purified their intention and proceed to decode with sincere rigor. The phrase preceding “I am but near,” is “When my servants ask about me, tell them: I am but near.” Asking is the beginning of a potential mystic search and deep longing.

At the core of Islamic Mysticism, or “Tassawuf,” or Sufism, is the Prophetic saying Whoever has found himself has found His Lord. In Sufi teaching, a human being navigates the signs, finding within, the truest self and the truest knowing of God. This can only happen through the careful, constant cultivation of love. The Sufi decodes all knowledge and all experience with one filter: love.

The antithesis of this painstakingly purified selfhood is the ego. Sufi training exposes the incessant suggestions of base desires– vanity, lust, greed etc– and rejects the ego as a matter of instinct, recognizing and excavating the Divine within. In Sufi Poetics, all humans, no matter the outward character or creed, carry God within, but exist in a state of forgetting; the word for Human in Arabic “Insaan” comes from “Ins” or “intimate love,” but “Insaan” is also composed of “nisyan” or “forgetfulness” – as a Prophetic tradition says. The human being is wont to be forgetful of her very essence: love.

Sufi poetics often makes use of intimate love in earthly form to explain God, the heavenly beloved. The litmus test of proximity to the Divine is the extent of discipline of the ego, paradoxically achieved not through the intellect but through passion. Access to that greatest love hinges on the confounding nature of the ego which poses as the self rather than the crude copy that it is– a principle most easily understood through love epics.

In studying the archetypes that Sufi poets employ, I find it useful to identify the three dynamics I mentioned earlier. Paradox: the stretching of the imagination and gaining the intelligence to negotiate contradictory reality in meaningful ways, the earthly beloved is at once a false idol and a means to the highest Truth. The second is presence, or the capacity to be awakened to sacred connection, and the third is pluralism: the core principle of Sufism that establishes that all beings share a single essence. Everything in the cosmos is a Divine expression, appearing in distinct, identifiable forms and ultimately converging on Divine mercy and majesty. God is “al–Haqq” or the Singular Reality and the complex circuitry of all existence is held together by His essence alone. Love’s ultimate expression embraces all.

In Sufi poetry, especially in narrative love poetry, the earthly beloved eludes the lover; the pursuit or union involves shedding of the ego through a harsh journey of self-evaluation against the great desire for closeness with the beloved.

I’ll briefly look at archetypes from two Qur’anic narrations that have inspired Sufi poets and the popular imagination in Muslim cultures for centuries. The story of the prophet Yusuf (Joseph) and Aziz e Misr Qitfir’s (Potiphar’s) wife Zuleikha, and the prophet Suleiman (Solomon) and Bilquees (Sheba), the queen of Saba (Sheba).

The Qur’an calls the narration of Yusuf’s life “a tale most beautiful.” The Persian poet Jami’s version “Yusuf o Zuleikha” written in 1485 is a Sufi interpretation of the Quranic original, an extension, one of several adaptations to enter popular culture as a Love Epic. These versions are built around Surah Yusuf but also draw from extra-scriptural sources, lore and mystic meaning-making.

A key facet of the story of Yusuf is the transformation from earthly to spiritual desire. Yusuf, who is endowed with half the beauty of the universe, is irresistible to Zuleikha. She begins her journey in a lustful passion, as a young woman of power and beauty, and ends it in repentance, a deepened self-awareness, humility, most importantly, the realization that true earthly love is a tributary of divine love. The transformation occurs when she becomes capable of perceiving beauty as a manifestation of character, a true reflection of the Divine, rather than a magnet for carnal desires.

In the Quranic allegory, Yusuf suffers injustice after injustice, first due to the jealousy of his brothers which causes him to be sold as a slave, then the snare of Zuleikha’s seduction that causes his imprisonment. In other words, Yusuf’s beauty makes him a target. The physical aspect of his beauty becomes a test for him and others. The jealous brothers fail the test, Zuleikha fails the test, only Yusuf passes by showing self-restraint, forbearance, wisdom.

As I think of archetypes, I wonder about the recurring image of Yusuf’s tunic; can it be considered a symbol of worldly temptation and ego? First, the tunic of his early youth that his brothers bring after throwing him in a well, returning home in pretend-grief over the killing of their younger brother in an attack by a wolf. Their father, the prophet Yaqub immediately understands that the brothers are lying: the shirt is bloody but intact, no signs of violence done by a wolf. The other tunic significant in the narrative is the one that Zuleikha, who attempts to seduce Yusuf, rips while attacking him. When caught, she accuses Yusuf for attacking her– but the tunic is found to be ripped from the back– a proof that he is innocent.

Yusuf’s brothers are blinded by jealousy, Zuleikha is blinded by lust — though Yusuf suffers despite his innocence, the tunic testifies and tells the truth against the overwhelming falsehoods.

Over time, Zuleikha as well as Yusuf’s brothers repent and understand that Yusuf’s beauty is no ordinary beauty, it is celestial, and he is above the base desires that they could not overcome as he did. Their transformation comes from understanding that Yusuf’s beauty represents moral character. His tunic, an outer vestment, is a symbol of how vulnerable our earthly selves are to the misguiding suggestions of the ego, but the very symbol of deception can also paradoxically serve to expose it.

The Qur’anic narration of Bilquis, the queen of Saba and the prophet Suleiman is replete with archetypes. On the surface it is a story of courtship between two rulers, but it yields remarkable spiritual discernment and wisdom and therefore makes great resource material for Sufi poets. I’ll focus on the symbolism of the throne, which the Quran uses to draw a clear contrast between the worldly and the eternal, and Rumi elaborates in his Mathnavi.

In the scriptural narration, Suleiman’s dominion includes the supernatural realm of the jinn, as well as birds and other creatures; he is known for his wisdom and worldly power. Saba rules over a people who worship the Sun instead of the one true God. Suleiman’s wooing of Bilquis is not only an offering of love and marriage, but a spiritual persuasion. She must learn to see power in perspective and question her belief in the false deity–

“Who comes for help at midnight, for the one who worships the sun?” as Rumi says on the topic of Saba’s creed.

Both Saba and Suleiman as rulers of a wide realm also depict the Sufi ideal of Pluralism, all beings sharing a single essence and serving the Divine in harmony.

In the Qur’anic narration the hoopoe bird, the archetypal messenger of love, reports to Suleiman, that Saba, “has a throne that is magnificent.” This is followed by a verse that delineates the world of illusion and Haqq, the true reality, followed by the verse:

“God. There is no god but He, the Lord of the glorious throne.”

In Rumi’s explanation, Saba’s throne symbolizes the body, the physicality of the self whose divestment is necessary for purifying the heart. Suleiman senses Presence in Saba, a propensity to overcome the ego and gain spiritual elevation. When she promises to visit Suleiman from Yemen to Jerusalem, she wishes for her throne, which Suleiman enables via his power over the jinn, knowing that she will herself discard this egoistic attachment. Rumi says:

Solomon saw that her heart was open to him

and that the throne would soon be left behind.

Let her bring it, he said.

It will soon become a lesson to her.

She can look at that throne

And see how far she has come.

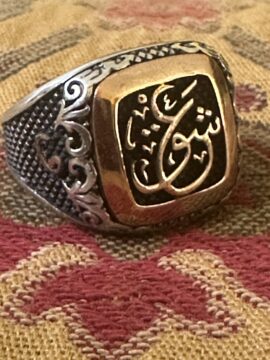

This is the essential alchemy of love: working the base metal of earthly attachment and turning it to the gold of spirit. The earthly beloved is a vehicle of truth that leads the lover to recognize it after the arduous work of confronting the ego in all its guises, and fulfilling her station as the noble human, insaan, the being that fights the forgetting and submits fully to love.