by Jochen Szangolies

If you spend any time in a place with public parks, gardens, or simple green areas fenced in squarely by concrete walkways, you’ll be familiar with the sight of trampled paths cutting across the grass, tracing a muddy connection through that which the street would lead you around. Depending on your mood and disposition, you might be annoyed by the sight: can’t people spend the extra few minutes to go around? Is their time really that valuable that they desperately have to cut their walk short by a few minutes? Can’t they just, well, keep off the lawn?

Or you might have perused such shortcuts yourself. Perhaps slightly sheepishly and with a vague sense of doing something forbidden, you reasoned that going all the way around to get to the bus stop is really too much of a bother—and besides, what if you miss your bus? Better to quickly dash through; it’s not like your own footprints will do all that much to deepen the path, anyway.

Or perhaps, you paused a while to wonder. Why is there a need for such a path? Evidently, enough people at point A wanted to go to point B using the shortest route to defy city planners by voting with their feet. Why wasn’t that path there in the first place?

From this point of view, such a desire path represent a failure of top-down planning to anticipate the bottom-up reality of the person in the street, so to speak. They’re a design flaw: after all, cities and the streets traversing them are (or ought to be) designed for the convenience of the humans inhabiting them. The layout the city planners intended is not a divine law, but an all-too-human best guess at what works; and desire paths are ways to demonstrate what doesn’t, not transgressions against the way things must be. In a design perfectly attuned to human needs, desire paths would be unnecessary. It’s not the people who cut across the grass that are at fault, it’s the layout of the streets that fails to conform to human needs.

Some concepts take this into account. Michigan State University, for instance, did not initially pave ways between its buildings, but waited for student-‘feetback’ (sorry, not sorry). In New York City, Broadway is said to be based on a Native American desire path. But by and large, we construct our public spaces by fiat: planners decide on the ways we ought to follow, and failure to do so may have repercussions, from disapproving looks from more upstanding citizens sticking to the straight and narrow to fines or tickets.

In terms of our public spaces, this may be little more than an annoyance (no matter on which side of the ‘keep off the grass’-debate you come down). However, when the same principles are applied to other parts of the public sphere, to laws and mores, codes of ‘proper’ conduct and ‘right’ ways of being, stakes may be much higher.

Social Spaces

When we talk about ‘space’ in everyday terms, we mostly mean the physical space around us—and there, mostly the two-dimensional surface of the Earth we are confined to. But in mathematics and physics, a ‘space’ is in general a more abstract notion, that generalizes some familiar notions beyond the mere concept of location.

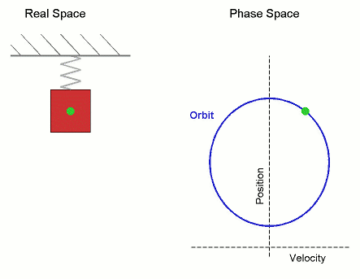

A baseball, once thrown, traces a parabolic arc through real space; its position at any given time is described by a set of three numbers, assuming a suitable system of coordinates. But just the set of coordinates at a single time doesn’t tell you everything about the ball. Is it just held in place there, or is it moving? If so, how—rising or falling? How fast is it going? Thus, to fully describe its motion, we need information about the direction it is moving, and its speed—we need another three numbers, describing its velocity (for technical reasons, physicists generally use the ball’s momentum, its velocity multiplied by its mass). Those six numbers—three for its position, three for its momentum—then yield a complete description of the ball’s motion.

A change in position or velocity—which, as Newton tells us, occurs if a force acts on the ball—then will result in the ball taking a particular path through this six-dimensional state space (generally called phase space by physicists, again for technical reasons that need not bother us here). In general, not every path will be allowed—ultimately, the physical laws tell us the possible paths of the ball.

We can add more relevant notions to our description. For instance, a ball isn’t just a single point of mass that can’t itself change; it can rotate, which might affect its motion through interaction with the surrounding air. It is also not a primitive particle, but composed of parts, and under circumstances unlikely to figure into regular baseball may be disassembled into these. Thus, we can add to our model, yielding a description of the changing state of the ball as a path through an ever-higher dimensional space.

We can imagine ourselves doing this—even if we can’t generally do so in practice—for ever more complex systems, in ever more abstract spaces. Consider, for example, clothing space: each point in this space is a possible set of clothing items a person might wear. Your changes of clothing during the day—changing your nightgown for your work clothes, then putting on a sports outfit for a run in the park, then a ratty old band shirt for the gig you attend at night—form a path through this space.

However, most points in clothing space don’t correspond to a likely state of dress. Sports bra, bowler hat and pantaloons are not exactly a common outfit. Likewise, most paths through this space won’t make for a likely sequence of outfits.

But here, we may start to wonder: if the laws of physics determine the possible paths through phase space, what determines allowed treks through the space of possible outfits? There’s nothing that physically prevents you from going to the pub in a bow tie, an undershirt, and a pair of MC Hammer pants. But you probably won’t do so. There are (largely) unspoken social rules that you believe you should follow, essentially because you believe that others believe you should follow them—that is, you don’t want to risk negative judgment by your peers.

There is a weird self-referential component to this. Your peers will only judge you negatively, upon violating the unspoken rules of proper dress, because they believe, in turn, that they would be judged thus. Social rules, then, are a kind of self-supporting structure, real only because a sufficient fraction of people believes them to be real. They are designs without a designer, even if some of them may be codified into laws (such as, for instance, laws against going naked in public). But in general, as with the designs of city planners, we think of them as just the way things are—or more perniciously, how they ought to be. Hence, cutting desire paths through social spaces often comes with great social costs—ostracism, abuse, or even violence.

A Random Walk Through Identity Space

In the (not so) good old times, identity was a solved problem. It’s just that the solution was terrible: who you are was, by and large, determined by the accidents of your birth—gender, race, status, location, and so on. The farmer’s son would take over the farm, the farmer’s daughter marry another farmer, and so it went. Your path through identity space was largely set by its initial conditions. It’s as if the city planners had only included a single path for each person, starting at their house—some leading to the palace, others straight into the workhouse. (This is ridiculously oversimplified, of course; but it will do as a guiding metaphor.)

Luckily, we have since managed to track a few new paths—even if we are still far away from equal access for everybody. But this increase in freedom or ‘social mobility’ also means that the once-solved (if badly) problem now is open, and finding a solution is not optional: we each are not only free to do so, but must choose some path to ‘find ourselves’. Staying home is not an option. On the one hand, this can be daunting: especially if taking the path less trodden, we might easily feel lost in the underbrush. On the other hand, the notions of where the path ‘ought to be’ are in steady flux, and one person’s desire path may look to another like stepping onto the wrong grass.

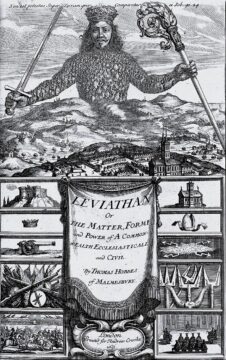

I believe that much of the tension of today stems from a lack of common understanding of these issues. By and large, we still think that our society works by fixed rules, that there are some right ways to live, and that, by extension, other ways are wrong. We take ourselves to live according to a social contract that specifies fixed rules, and we condemn those that seem to flout them. Many of the ‘creation myths’ of society exemplify this sort of thinking, from the Hobbesian Leviathan that holds supreme power to safeguard against a natural state of war of ‘all against all’, to the Rawlsian ‘veil of ignorance’ that obscures their place in society to those that come together to create it.

All of these are, essentially, ‘city planner’-types of stories that seek to lay down the paths everybody ought to follow. Failing to follow them is then a breach of social contract; thus, ‘desire paths’ in society remove those who follow them from it. Modes of identity and ways of being that aren’t part of the original plan are implicitly deemed wrong, or in violation of social mores. Moreover, allowing for new paths is not the same as allowing for freedom of movement. We may have more paths available to choose from today, but that’s not the same as being open to people finding their own ways.

It should be remembered that a desire path is a visible expression of a statistical regularity: most people will take this path most of the time. But in order for such a path to form, we must first allow for people deviating from the path—the original, concrete, city-planner path, that is. It would then not do to simply fix the desire path as just an updated version of the old one: desire paths, by their nature, must remain unpaved, to allow for their variance. It is those not taking the pre-set path that end up creating new ones.

What this means is that we should not confuse (statistical) regularity with norms. Just because most people behave a certain way most of the time, doesn’t mean that people in general ought to behave that way—indeed, that inference only serves to impede further progress.

On the other hand, this should not be misunderstood as an argument that ‘anything goes’. Desire paths only emerge out of stable regularities; it’s just that it often doesn’t work to try and mandate such regularities top-down, rather than having them emerge bottom-up. As an example, take the meaning of words: generally, despite the best attempts by grumpy self-declared language purists, words will change both their meaning and shape over time. That is, a word will trace a certain path through language-space, with both its form and its meaning today having evolved from a certain original root. Words are defined by their usage, not by city-planner type guardians of proper language.

But from that, it doesn’t follow that any word could mean anything at all. Humpty Dumpty’s words may mean whatever he wants them to mean, but the price of this is a failure of being understood. Words don’t exist in isolation, but as part of a community; and so, too, is it the community of word-users that determine their meanings. If every word were to go it alone, tracing out its lone path, communication would become impossible.

It’s also important to note that this doesn’t make the issue a purely subjective one. While we are, in principle, free to choose any path we want (or ought to be), not every path will be sensible. A desire path, after all, represents an objective statistical regularity, created by a material need. These needs are just as real with personal identity, and not a mere matter of choice or convenience.

As so very often, then, between the extremes of fixed, top-down rules and full-on bottom-up anarchy, we find we have to muddle through the middle. Straying off the beaten path is not wrong in itself, no matter the harrumphing of ‘keep off the grass’-types of self-appointed guardians of right and proper ways of being; but paths only become paths through the collective action of many feet.

The business of finding our selves, in the absence of a fixed path to follow, is a delicate and fraught one, and one that can only succeed with the support of those around us, rather than against their scorn and derision. The good news is that we all face this problem, no matter whether we stick to the paved roads or walk the path less travelled.