by Michael Liss

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. —Abraham Lincoln, departing Springfield, Illinois, for his Inauguration, February 11, 1861

“A task greater than that which rested on Washington.” Lincoln as Oedipus? George Washington as Laius, to be slain by his son? There are a lot of myths that have sprung up around Lincoln. Some put him in the company of saints. Others, mostly coming from a Lost Cause perspective, place him a lot closer to Hades. Still, it seems a deep dive into myth to ascribe to a resentment of George Washington the life force that vaulted Lincoln from poverty and obscurity through sectional and then national prominence, then to the White House, and from there to winning the Civil War and freeing millions from bondage.

Yes, it’s the Oedipus myth, say a group of historians, including George Forgie, Dwight Anderson, and Charles Strozier. To Lincoln’s eternal damnation, he unquestionably had an Oedipus Complex, according to the renowned critic and essayist Edmund Wilson. Not so, forcefully, and even a little angrily, argue Richard M. Current, the “Dean of the Lincoln Scholars” (“Lincoln After 175 Years: The Myth of the Jealous Son”) and Garry Wills (Lincoln At Gettysburg).

The “source code” for this dispute largely derives from a speech given by Lincoln on January 27, 1838: “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions: Address Before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. The “Young Men” part applies to Lincoln as well. He is just short of his 29th birthday, and a Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from Sangamon County. If anyone in his audience that day (besides, perhaps, Lincoln himself) thought that he might be a future President of the United States, that listener’s name is lost to history. Read more »

Kevin Beasley. Reunion.

Kevin Beasley. Reunion.

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

My favorite bookstore closed this month. Well, my favorite bookstore in Zurich, where I live. Also it hasn’t actually closed, it’s only changing hands. But

The season finale of

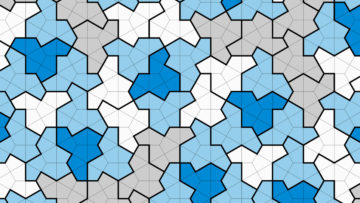

The season finale of  A 13-sided shape known as “the hat” has mathematicians tipping their caps.

A 13-sided shape known as “the hat” has mathematicians tipping their caps. The specter of parental neglect no longer orders U.S. politics as it did in the late twentieth century. But as indispensable recent books by sociologists Lynne Haney and Dorothy Roberts demonstrate, the knotty legal infrastructures and punitive policies inspired by this rhetoric have endured, with devastating consequences for poor families. These books focus on different areas of U.S. family policy—Haney writes about child support enforcement, Roberts about child protective services—but together they expose the state’s massive and creeping apparatus for surveilling and disciplining parents.

The specter of parental neglect no longer orders U.S. politics as it did in the late twentieth century. But as indispensable recent books by sociologists Lynne Haney and Dorothy Roberts demonstrate, the knotty legal infrastructures and punitive policies inspired by this rhetoric have endured, with devastating consequences for poor families. These books focus on different areas of U.S. family policy—Haney writes about child support enforcement, Roberts about child protective services—but together they expose the state’s massive and creeping apparatus for surveilling and disciplining parents. David Baddiel was six years old when his mother told him death was like a long sleep from which you never wake up. “I think from that point,” he says, “I never really wanted to go to sleep again.” That night, he lay on the top bunk of his bed, fervently praying – “probably” the first and last time he has prayed with any sincerity – that “my life as it was in Dollis Hill in 1971 would still somehow continue after death”.

David Baddiel was six years old when his mother told him death was like a long sleep from which you never wake up. “I think from that point,” he says, “I never really wanted to go to sleep again.” That night, he lay on the top bunk of his bed, fervently praying – “probably” the first and last time he has prayed with any sincerity – that “my life as it was in Dollis Hill in 1971 would still somehow continue after death”.