by Tim Sommers

My wife Stacey is irritated with the way Netflix’s machine learning algorithm makes recommendations. “I hate it,” she says. “Everything it recommends, I want to watch.”

On the other hand, I am quite happy with Spotify’s AI. Not only does it do pretty well at introducing me to bands I like, but also the longer I stay with it the more obscure the bands that it recommends become. So, for example, recently it took me from Charly Bliss (76k followers), to Lisa Prank (985 followers), to Shari Elf (33 followers). I believe that I have a greater appreciation for bands that are more obscure because I am so cool. Others speculate that I follow more obscure bands because I think it makes me cool while, in fact, it shows I am actually uncool. Whatever it is, Spotify tracks it. The important bit is that it doesn’t just take me to more and more obscure bands. That would be too easy. It takes me more and more obscure bands that I like. Hence, it successfully tracks my coolness/uncoolness.

The proliferation of AI “recommenders” seems relatively innocuous to me – although not to everyone. Some people worry about losing the line between when they just like what the AI recommends to them, and when they adapt to like what the AI says they should like. But that just means the AI is part of their circle of friends now, right? It’s the proliferation of AIs into more fraught kinds of decision-making that I worry about.

AIs are used to decide who gets a job interview, who gets granted parole, who gets most heavily policed, and who gets a new home loan. Yet there’s evidence that these AIs are systematically biased. For example, there is evidence that a widely-used system designed to predict whether offenders are likely to reoffend or commit future acts of violence – and, hence, to set bail, determine sentences, and set parole – exhibits racial bias. So, too several AIs designed to predict crime ahead of time, to guide policing (a pretty Philip K. Dickian idea already). Amazon discovered, for themselves, that their hiring algorithm was sexist. Sexist, racists, anti-LGBTQA+. anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslin language is endemic among large-language models. Read more »

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough.

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough. Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import. Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

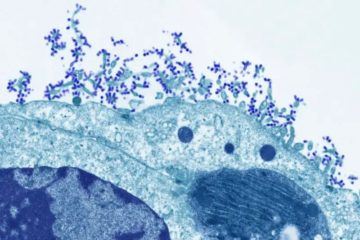

Soon after the pandemic commenced its

Soon after the pandemic commenced its  There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published  This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s. Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh.

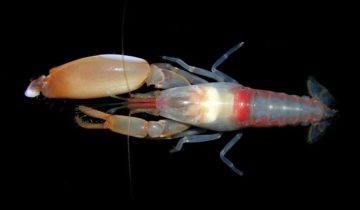

Is any product of bourgeois consumer ideology more noxious than the “bucket list”? At just the moment a person should be adjusting their orientation, in conformity with their true nature, to focus exclusively on the horizon of mortality, they are rudely solicited one last time, before it’s really too late, for a final blow-out tour of the amusement parks and spectacles that still held out some plausible hope of providing satisfaction back in ignorant youth, when life could still be imagined to be made up of such things. “Travel is a meat thing”, William Gibson wrote, to which we might add that the quest for new experiences in general is really only fitting for those whose meat is still fresh. An experimental

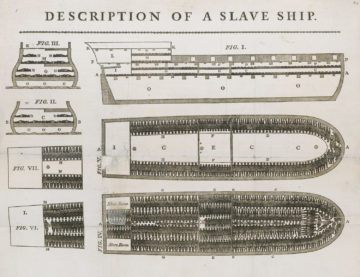

An experimental  Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument?

Asterisk: Your book Moral Capital is about why the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain happened in the late 1780s and not earlier. Would you mind briefly walking through the thrust of that argument? 3:16: What made you become a philosopher?

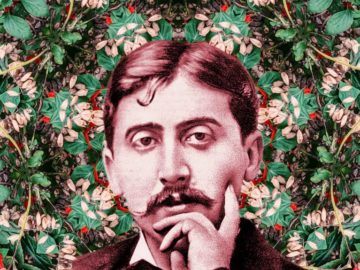

3:16: What made you become a philosopher? One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“

One hundred years ago, on Nov. 18, 1922, Marcel Proust breathed his last in Paris at age 51. His death, from pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess, was perhaps the final nail in the coffin of the belle epoque, an age of gentility, civility and artistic achievement that had mostly ended with the outbreak of World War I. At the time, several volumes of Proust’s gargantuan, seven-part novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu” (“ I recently shared a

I recently shared a  Michael Pettis in American Compass:

Michael Pettis in American Compass: