by Rafiq Kathwari

When I was ten, Grandpa drove me on a crisp autumn evening to see geese, gulls, and ducks descend with expanded wings on Wular. “Asia’s largest freshwater lake,” he said. “They fly in disciplined formation like copper-tipped arrows across the desolation of sky, along Himalayan foothills, arcing between Mughal domes from Kashgar to Kashmir.”

I remember, a pristine mirror polished by the breeze. Geese glinted in wild ochre, gulls mottled in brown, ducks in gold. “We measure time,” Grandpa said, “by their arrival and departure.” On the foothills, encircled by grand mountains white turbans on peaks, trees their grand architecture revealed. Rushlight induced a silence I can still hear 50 years later, at dawn in March as I park

my car across an army bunker secured by barbed wire. Bold white letters on a signpost sound like a mantra: Respect All Suspect All. Soldiers on a watchtower stare at me as I step down to a lookout gazebo.

My heart sinks: strips of land, mud, and peat float on a sullied mirror as do lotus leaves. Foothills are bare, no trees only stump after stump after stump. Weeds are heaped on paddle boats. Walnut saplings line the shore. Freshly axed logs are stacked high. An odd colony of gabled homes has encroached the banks. Rubbish is strewn near a cowshed next to an outhouse. An open drain moves all things raw into the lake. Swallows perched on power lines are sharp and flat notes.

A lone signal tower is flashing red. A tubular beam of sunlight pierces the clouds, spotlighting a flight of ducks emerging from the shelter of water lilies. Flapping their wings rapidly, they ascend from a childhood sanctuary, now the world’s most militarized place. A nightingale perched on the gazebo sings, Respect all Suspect all Respect all Suspect all . . .

for Justine Hardy

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book What We Owe The Future have recently been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times, Vox, NPR, BBC, The Atlantic, Wired, and Boston Review. He’s been interviewed by Sam Harris, Ezra Klein, Tim Ferriss, Dwarkesh Patel, and Tyler Cowen. Tweeted about by Elon Musk, Andrew Yang, and Matt Yglesias. The publicity spike is no mystery: the effective altruist movement is well-funded and well-organized, they decided to burn “long-termism” into the collective consciousness, and they sure succeeded.

If the point of publishing a book is to have a public relations campaign, Will MacAskill is the greatest English writer since Shakespeare. He and his book What We Owe The Future have recently been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times, Vox, NPR, BBC, The Atlantic, Wired, and Boston Review. He’s been interviewed by Sam Harris, Ezra Klein, Tim Ferriss, Dwarkesh Patel, and Tyler Cowen. Tweeted about by Elon Musk, Andrew Yang, and Matt Yglesias. The publicity spike is no mystery: the effective altruist movement is well-funded and well-organized, they decided to burn “long-termism” into the collective consciousness, and they sure succeeded.

When considering environmental issues, the usual rallying cry is that of “saving the planet”. Rarely do people acknowledge that, rather, it is us who need saving from ourselves. We have appropriated ever-larger parts of Earth for our use while trying to separate ourselves from it, ensconced in cities. But we cannot keep the forces of life at bay forever. In A Natural History of the Future, ecologist and evolutionary biologist Rob Dunn considers some of the rules and laws that underlie biology to ask what is in store for us as a species, and how we might survive without destroying the very fabric on which we depend.

When considering environmental issues, the usual rallying cry is that of “saving the planet”. Rarely do people acknowledge that, rather, it is us who need saving from ourselves. We have appropriated ever-larger parts of Earth for our use while trying to separate ourselves from it, ensconced in cities. But we cannot keep the forces of life at bay forever. In A Natural History of the Future, ecologist and evolutionary biologist Rob Dunn considers some of the rules and laws that underlie biology to ask what is in store for us as a species, and how we might survive without destroying the very fabric on which we depend. Mikhail S. Gorbachev, whose rise to power in the Soviet Union set in motion a series of revolutionary changes that transformed the map of Europe and ended the Cold War that had threatened the world with nuclear annihilation, has died in Moscow. He was 91.

Mikhail S. Gorbachev, whose rise to power in the Soviet Union set in motion a series of revolutionary changes that transformed the map of Europe and ended the Cold War that had threatened the world with nuclear annihilation, has died in Moscow. He was 91. Much

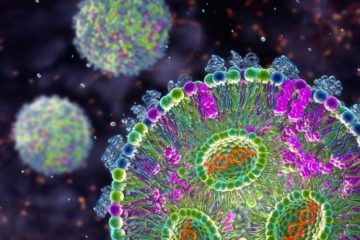

Much Can messenger RNA (mRNA) train the immune system to attack cancers that resist conventional treatments? To find out, researchers at Atlantic Health System are conducting

Can messenger RNA (mRNA) train the immune system to attack cancers that resist conventional treatments? To find out, researchers at Atlantic Health System are conducting  There are some artists, scientists, and economists whose oeuvre is significant for philosophers even though we generally overlook them. This occurs because too often we deem worthy of philosophical interpretation only other philosophers and their investigations. But there are figures who have provided philosophers with new cultural, scientific, and political paradigms who are absent from our philosophical traditions. Although we could say they were philosophers without defining themselves as such, their works have often presented innovative concepts, meanings, and truths that give them the same ontological status as the work of other philosophers. For most continental thinkers—as analytic philosophers still believe our discipline is circumscribed exclusively to logical problems derived from mathematics and science—these figures are vital to understanding our past, present, and also future.

There are some artists, scientists, and economists whose oeuvre is significant for philosophers even though we generally overlook them. This occurs because too often we deem worthy of philosophical interpretation only other philosophers and their investigations. But there are figures who have provided philosophers with new cultural, scientific, and political paradigms who are absent from our philosophical traditions. Although we could say they were philosophers without defining themselves as such, their works have often presented innovative concepts, meanings, and truths that give them the same ontological status as the work of other philosophers. For most continental thinkers—as analytic philosophers still believe our discipline is circumscribed exclusively to logical problems derived from mathematics and science—these figures are vital to understanding our past, present, and also future. David Ferrucci, who led the team that built IBM’s famed Watson computer, was elated when it beat the best-ever human “Jeopardy!” players in 2011, in a televised triumph for artificial intelligence.

David Ferrucci, who led the team that built IBM’s famed Watson computer, was elated when it beat the best-ever human “Jeopardy!” players in 2011, in a televised triumph for artificial intelligence. The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than

The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than  In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside.

In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside. The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies.

The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies.![Righting America at the Creation Museum (Medicine, Science, and Religion in Historical Context) by [Susan L. Trollinger, William Vance Trollinger]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/511yK1hsSBL.jpg)

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz.

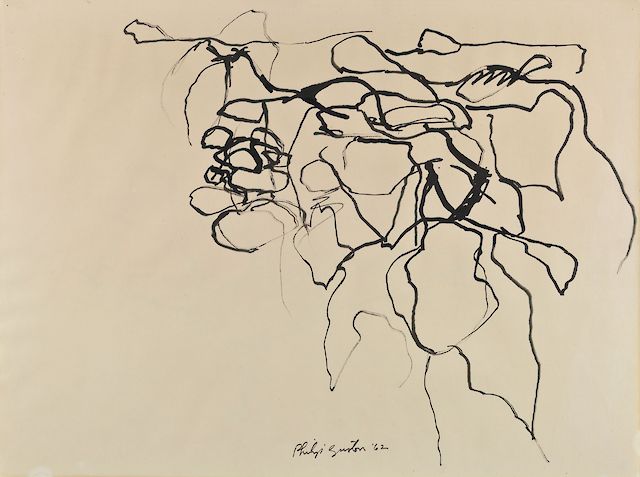

Herschel Walker claims that we have enough trees already, that we send China our clean air and they return their dirty air to us, that evolution makes no sense since there are still apes around, and freely offers other astute scientific insights. He may be among the least knowledgeable (to put it mildly) candidates running for office, but he’s not alone and many candidates, I suspect, are also surprisingly innocent of basic math and science. Since innumeracy and science illiteracy remain significant drivers of bad policy decisions, it’s not unreasonable to suggest that congressional candidates (house and senate) be obliged to get a passing grade on a simple quiz. Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

Philip Guston. Still Life, 1962.

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of

I recently listened to a discussion on the topic of