Leo Robson in New Statesman:

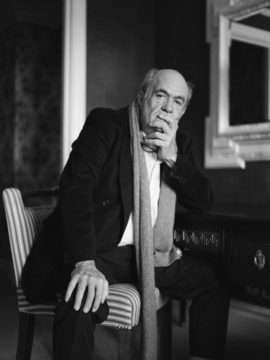

In conversation, the Irish writer Colm Tóibín, the winner of the 2021 David Cohen Prize for Literature, employs a range of corroborating gestures. During moments of leisurely explanatory flow, he uses the back of his right hand to fondle the air just in front of him, or to fold it in gentle Nigella-ish revolutions. When he wants to achieve a tone of emphasis, a stab of the index finger accompanies every carefully chosen word. In more pensive moments, he likes to stroke his head, which is bald except for tufts around the back and side in the manner of his hero Henry James, the subject of his novel The Master (2004). On a recent afternoon, sitting in a library-like, though bookless, room in a small central London hotel, he preferred to lean forward from his armchair, arching his noble lined face towards the coffee table that lay between us – a disposition that reflected the infinite seriousness with which he takes “the creation of character and setting of scenes”.

In conversation, the Irish writer Colm Tóibín, the winner of the 2021 David Cohen Prize for Literature, employs a range of corroborating gestures. During moments of leisurely explanatory flow, he uses the back of his right hand to fondle the air just in front of him, or to fold it in gentle Nigella-ish revolutions. When he wants to achieve a tone of emphasis, a stab of the index finger accompanies every carefully chosen word. In more pensive moments, he likes to stroke his head, which is bald except for tufts around the back and side in the manner of his hero Henry James, the subject of his novel The Master (2004). On a recent afternoon, sitting in a library-like, though bookless, room in a small central London hotel, he preferred to lean forward from his armchair, arching his noble lined face towards the coffee table that lay between us – a disposition that reflected the infinite seriousness with which he takes “the creation of character and setting of scenes”.

“What you do,” he told me, at a moment of near horizontality, “is play to your strengths. But you keep not knowing what your strengths are.” He was talking about the evolution of his latest book, The Magician, a kind of sibling to The Master, which follows the German writer Thomas Mann virtually from cradle to grave. “You keep thinking, ‘I must be deep, I must be deeper.’ Then you say, stop this nonsense, get on with the story.” Eventually, he decided that he was “creating an illusion. The effort is to be immersive, so the reader can live this life emotionally, in a vicarious way.”

Tóibín was born, 66 years ago, to a conservative Catholic family, in Enniscorthy, County Wexford. His grandfather was an IRA member who took part in the Easter Rising. His father, a teacher, died when he was 12. As a teenager, at boarding school, Tóibín discovered literature and realised he was gay. After graduating from University College Dublin he moved to Barcelona, inspired partly by his love of Ernest Hemingway, in the final days of Franco, when the city was blooming with new freedoms.

More here.

In the spring of 1991, the Romanian comparative-religionist Ioan Petru Culianu was shot to death while seated in a toilet stall near his office in Swift Hall on the campus of the University of Chicago. A single Winchester .25 bullet to the back of the head suggested the work of a trained assassin, who had swooped down upon him from over the wall of the neighboring stall like a hawk.

In the spring of 1991, the Romanian comparative-religionist Ioan Petru Culianu was shot to death while seated in a toilet stall near his office in Swift Hall on the campus of the University of Chicago. A single Winchester .25 bullet to the back of the head suggested the work of a trained assassin, who had swooped down upon him from over the wall of the neighboring stall like a hawk. Omicron is so contagious that it is still flooding hospitals with sick people. And America’s continued inability to control the coronavirus has deflated its health-care system, which can no longer offer the same number of patients the same level of care.

Omicron is so contagious that it is still flooding hospitals with sick people. And America’s continued inability to control the coronavirus has deflated its health-care system, which can no longer offer the same number of patients the same level of care.  I’d be amazed if you couldn’t sense it—the coming end of things. A woman sits by her grandmother in a St. Louis, Miss., ICU, the older woman about to be intubated because Covid has destroyed her lungs, but until a day before she insisted that the disease wasn’t real. In Kenosha, Wisc., a young man discovers that even after murdering two men a jury will say that homicide is justified, as long as it’s against those whose politics the judge doesn’t like. Similar young men take note. Somebody’s estranged father drives to Dallas, where he waits outside of Deeley Plaza alongside hundreds of others, expecting the emergence of JFK Jr. whom he believes is coming to crown the man who lost the last presidential election. Somewhere in a Menlo Park recording studio, a dead eyed programmer with a haircut that he thinks makes him look like Caesar Augustus stares unblinkingly into a camera and announces that his Internet services will be subsumed under one meta-platform, trying to convince an exhausted, anxious, and depressed public of the piquant joys of virtual sunshine and virtual wind. At an Atlanta supermarket, a cashier who made minimum wage, politely asks a customer to wear a mask per the store’s policy; the customer leaves and returns with a gun, shooting her. She later dies.

I’d be amazed if you couldn’t sense it—the coming end of things. A woman sits by her grandmother in a St. Louis, Miss., ICU, the older woman about to be intubated because Covid has destroyed her lungs, but until a day before she insisted that the disease wasn’t real. In Kenosha, Wisc., a young man discovers that even after murdering two men a jury will say that homicide is justified, as long as it’s against those whose politics the judge doesn’t like. Similar young men take note. Somebody’s estranged father drives to Dallas, where he waits outside of Deeley Plaza alongside hundreds of others, expecting the emergence of JFK Jr. whom he believes is coming to crown the man who lost the last presidential election. Somewhere in a Menlo Park recording studio, a dead eyed programmer with a haircut that he thinks makes him look like Caesar Augustus stares unblinkingly into a camera and announces that his Internet services will be subsumed under one meta-platform, trying to convince an exhausted, anxious, and depressed public of the piquant joys of virtual sunshine and virtual wind. At an Atlanta supermarket, a cashier who made minimum wage, politely asks a customer to wear a mask per the store’s policy; the customer leaves and returns with a gun, shooting her. She later dies. WHEN POETS DIE YOUNG,

WHEN POETS DIE YOUNG, David Bennett, 57, is doing well three days after the experimental seven-hour procedure in Baltimore, doctors say. The transplant was considered the last hope of saving Mr Bennett’s life, though it is not yet clear what his long-term chances of survival are. “It was either die or do this transplant,” Mr Bennett explained a day before the surgery. “I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,” he said. Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center were granted a special dispensation by the US medical regulator to carry out the procedure, on the basis that Mr Bennett – who has terminal heart disease – would otherwise have died.

David Bennett, 57, is doing well three days after the experimental seven-hour procedure in Baltimore, doctors say. The transplant was considered the last hope of saving Mr Bennett’s life, though it is not yet clear what his long-term chances of survival are. “It was either die or do this transplant,” Mr Bennett explained a day before the surgery. “I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice,” he said. Doctors at the University of Maryland Medical Center were granted a special dispensation by the US medical regulator to carry out the procedure, on the basis that Mr Bennett – who has terminal heart disease – would otherwise have died. I

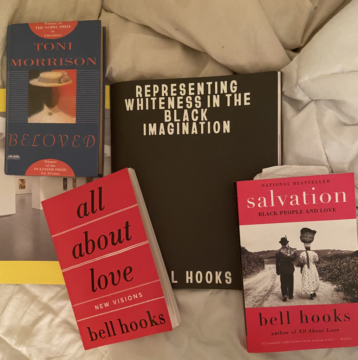

I Reading hooks transformed my thinking on a bevy of subjects, including feminism, Buddhism, Christianity, celebrity, sex, romance, and the limits and possibilities of representation. In her 2003 book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, she notes that “throughout our history in this nation African-Americans have had to search for images of our ancestors.” This is true of my own search for biological forebears, but in terms of intellectual heritage, I feel lucky that I didn’t have to search very far to find the images hooks conjured in words, or the actual photographs of her on dust jackets. She was incredibly prolific, and her books were everywhere when I was coming of age. Since my teens, I’ve enjoyed the slow burn of revelation that comes through encountering and reencountering her work. I’ve learned the importance of being patient enough to let meaning reach me when I’m ready for it, allowing an insight to land slowly and settle in my mind. Rereading hooks has helped me to revel in ideas without necessarily articulating them to anyone but myself, lest I interrupt the process of recognition by blabbing what I think I know too soon. As the old folks say, some things can remain private, and these reading experiences that overwrite each other and take years to develop are among the most pleasurable.

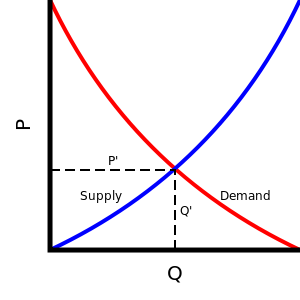

Reading hooks transformed my thinking on a bevy of subjects, including feminism, Buddhism, Christianity, celebrity, sex, romance, and the limits and possibilities of representation. In her 2003 book We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, she notes that “throughout our history in this nation African-Americans have had to search for images of our ancestors.” This is true of my own search for biological forebears, but in terms of intellectual heritage, I feel lucky that I didn’t have to search very far to find the images hooks conjured in words, or the actual photographs of her on dust jackets. She was incredibly prolific, and her books were everywhere when I was coming of age. Since my teens, I’ve enjoyed the slow burn of revelation that comes through encountering and reencountering her work. I’ve learned the importance of being patient enough to let meaning reach me when I’m ready for it, allowing an insight to land slowly and settle in my mind. Rereading hooks has helped me to revel in ideas without necessarily articulating them to anyone but myself, lest I interrupt the process of recognition by blabbing what I think I know too soon. As the old folks say, some things can remain private, and these reading experiences that overwrite each other and take years to develop are among the most pleasurable. Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Every Econ 101 student learns the basic model of demand and supply. It’s pretty straight forward. Picture a graph with the price of a product or service on the vertical axis and the quantity supplied and demanded on the horizontal axis. There are two curves drawn on this graph: the demand curve and the supply curve. The demand curve is downward sloping because as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more. The supply curve is upward sloping because producers are willing to supply more when they are paid more. The “competitive equilibrium price” of the product or service is where supply equals demand: two curves intersect. When prices are higher than the equilibrium price, supply is greater than demand: there is “excess supply”. This makes sense: at higher prices, suppliers are going to be happy to sell more, but consumers aren’t willing to buy as much.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022.

Sughra Raza. First Snow 2022. On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity.

On the anniversary of the attempt by Donald Trump and some of his supporters to subvert the 2020 US presidential election, Joe Biden denounced those who “place a dagger at the throat of democracy.” To which one can only say: About bloody time! The threat posed by Trump and the Republican party to America’s democratic institutions–highly imperfect though they are–is so obvious that anyone who has a bully pulpit should be pounding out a warning at every opportunity. A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).

A large number of jobs exist not because they create economic value but because they make business sense given the institutions we have – customer expectations, bureaucratic regulations, and so on. They do not solve a real problem but a fake problem created by inefficient institutions. They therefore do not make our society better off but rather they represent a great cost to society – of many people’s time being expended on something fundamentally pointless instead of something worthwhile. One way of spotting such anti-jobs is to compare staffing in the same industry across different countries. US supermarkets employ people just to greet customers and bag groceries, for example, which would seem a ridiculous waste of time in most of the world. In Japan one can find people standing in front of road construction waving a flag (they are replaced with mechanical manikins on nights and weekends).