Gerald Early in The Common Reader:

As Lisa Morton notes in Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances, there is not a shred of scientific evidence that proves the existence of spirits or any ability on our part or theirs, if they did exist, that we can communicate with them. (298) Despite this, there is hardly a culture or people on earth that has not or does not believe in a spiritual life of some sort after death and that does not have some sort of ritual conducted by a “specialist” to communicate with the dead. Human beings are convinced, and have been throughout history, that there is an afterlife, that death is not the end but simply a gateway to more life, and that this afterlife has some profound effect upon those still living this life. What this pervasive belief shows is:

As Lisa Morton notes in Calling the Spirits: A History of Seances, there is not a shred of scientific evidence that proves the existence of spirits or any ability on our part or theirs, if they did exist, that we can communicate with them. (298) Despite this, there is hardly a culture or people on earth that has not or does not believe in a spiritual life of some sort after death and that does not have some sort of ritual conducted by a “specialist” to communicate with the dead. Human beings are convinced, and have been throughout history, that there is an afterlife, that death is not the end but simply a gateway to more life, and that this afterlife has some profound effect upon those still living this life. What this pervasive belief shows is:

• First, that we cannot imagine non-existence or fervently do not want to; for us, life only begets more life, good or gruesome, material or trans-material.

• Second, that there is an essential loneliness about human existence that makes us want to be surrounded by ghosts, spirits, gods, and the like who mean us either good or harm; to be alone frightens us more than evil spirits do.

• Third, that science has far less influence on our thinking than we might claim, that science has its limits in our understanding and shaping of the real and the unreal, that we believe we live in a world that requires propitiation as much as it does governance and stewardship, a world that remains as much supernatural as it is natural.

More here.

If my father occasionally enjoyed falsifying his ancestry for a bit of role-playing fun on the French Riviera (I don’t believe it ever went very far, though he may once have gained admission with this ruse to a party at the vacation home of Sally Jessy Raphael), I have tended to adopt the opposite evolutionary strategy as I move through rather different social circles than those I may once have been expected to end up in. When an animal is threatened, it can puff itself up to appear even more threatening than its adversary, as a cat does; or it can lie prostrate like an opossum, even generating from within its living body the stench of death itself. While I have never been so desperate as to slip into thanatosis, I have often gone out of my way to imply, in rarefied social settings, that my own origins “stink”, that I come from the pure stock of Dustbowl migrants, from a sort of topsy-turvy farce of aristocracy in which you convince others that you are somebody precisely by establishing that you are descended from absolutely nobody.

If my father occasionally enjoyed falsifying his ancestry for a bit of role-playing fun on the French Riviera (I don’t believe it ever went very far, though he may once have gained admission with this ruse to a party at the vacation home of Sally Jessy Raphael), I have tended to adopt the opposite evolutionary strategy as I move through rather different social circles than those I may once have been expected to end up in. When an animal is threatened, it can puff itself up to appear even more threatening than its adversary, as a cat does; or it can lie prostrate like an opossum, even generating from within its living body the stench of death itself. While I have never been so desperate as to slip into thanatosis, I have often gone out of my way to imply, in rarefied social settings, that my own origins “stink”, that I come from the pure stock of Dustbowl migrants, from a sort of topsy-turvy farce of aristocracy in which you convince others that you are somebody precisely by establishing that you are descended from absolutely nobody. Many writers and researchers suggested that the presence of a high-containment laboratory in Wuhan, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, could point to a laboratory origin for the pandemic: a bioweapons experiment; or

Many writers and researchers suggested that the presence of a high-containment laboratory in Wuhan, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, could point to a laboratory origin for the pandemic: a bioweapons experiment; or  When journalist

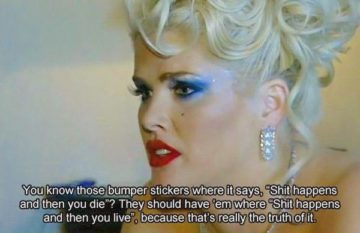

When journalist  Here was a woman who had modelled her life so closely on Marilyn Monroe’s that doing so eventually helped drive her to her death – the blonde waves and the fake breasts; the pill addictions and the airheaded pronouncements about men and sex and diamonds; the years spent tumbling down the rabbit-hole in search of somebody with cash willing to play at being Daddy; the PLAYBOY cover and centrefold, and the unwise sexual exhibitionism, and the occasional moments of bleak honesty that nodded at some formative abuse – and yet still she achieved twice the thing that Monroe never did: for four days, from 7 September 2006 to 10 September 2006, Anna Nicole Smith was a mother to two children. As it had for Monroe, who confessed in her last year that she had wanted children ‘more than anything’, motherhood held as much significance for Smith as big-time fame did, her desire to be the world’s hottest chick only commensurate with her certainty that she should procreate. ‘I’m either going to be a very good, very famous movie star and model,’ Smith told ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY at the height of her success, in 1994, ‘or I’m going to have a bunch of kids. I would miss having a career, but I’ve done my acting, and I’ve done my modelling. I’ve done everything I wanted to do.’ She did not become a great actor, even if for a short time she was one of the biggest models on earth. She did not make it to 40, even though she outlived Monroe by 3 sad, medicated years, dying at the Hard Rock Hotel in Florida at just 39 years old, in 2007.

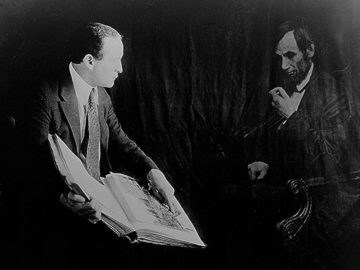

Here was a woman who had modelled her life so closely on Marilyn Monroe’s that doing so eventually helped drive her to her death – the blonde waves and the fake breasts; the pill addictions and the airheaded pronouncements about men and sex and diamonds; the years spent tumbling down the rabbit-hole in search of somebody with cash willing to play at being Daddy; the PLAYBOY cover and centrefold, and the unwise sexual exhibitionism, and the occasional moments of bleak honesty that nodded at some formative abuse – and yet still she achieved twice the thing that Monroe never did: for four days, from 7 September 2006 to 10 September 2006, Anna Nicole Smith was a mother to two children. As it had for Monroe, who confessed in her last year that she had wanted children ‘more than anything’, motherhood held as much significance for Smith as big-time fame did, her desire to be the world’s hottest chick only commensurate with her certainty that she should procreate. ‘I’m either going to be a very good, very famous movie star and model,’ Smith told ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY at the height of her success, in 1994, ‘or I’m going to have a bunch of kids. I would miss having a career, but I’ve done my acting, and I’ve done my modelling. I’ve done everything I wanted to do.’ She did not become a great actor, even if for a short time she was one of the biggest models on earth. She did not make it to 40, even though she outlived Monroe by 3 sad, medicated years, dying at the Hard Rock Hotel in Florida at just 39 years old, in 2007. Harry Houdini was just 52 when he

Harry Houdini was just 52 when he  Cora Currier in The New Republic:

Cora Currier in The New Republic: Aziz Z. Huq in Boston Review:

Aziz Z. Huq in Boston Review:

A

A  “You’re just a pawn in the game, you know,” a public security officer summarily informs Ai Weiwei, China’s most controversial — and to the Chinese Communist Party, its most dangerous — artist. It is 2011 and Ai, suspected of “inciting the subversion of state power,” has recently been held captive for 81 days; soon after his release, he is slapped with a tax bill equivalent to $2.4 million. According to the officer, Ai’s high profile has made him an expedient tool for Westerners to attack China, but “pawns sooner or later all get sacrificed.” Of course, it’s obvious that Ai also regards the officer as a pawn, one who, in serving an oppressive regime, has sacrificed his freedom to speak for himself.

“You’re just a pawn in the game, you know,” a public security officer summarily informs Ai Weiwei, China’s most controversial — and to the Chinese Communist Party, its most dangerous — artist. It is 2011 and Ai, suspected of “inciting the subversion of state power,” has recently been held captive for 81 days; soon after his release, he is slapped with a tax bill equivalent to $2.4 million. According to the officer, Ai’s high profile has made him an expedient tool for Westerners to attack China, but “pawns sooner or later all get sacrificed.” Of course, it’s obvious that Ai also regards the officer as a pawn, one who, in serving an oppressive regime, has sacrificed his freedom to speak for himself. Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study.

Contemporary Americans have access to custom workout routines, fancy gyms, and high-end home equipment like Peloton machines. Even so, when it comes to physical activity, our forebears of two centuries ago beat us by about 30 minutes a day, according to a new Harvard study. If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times.

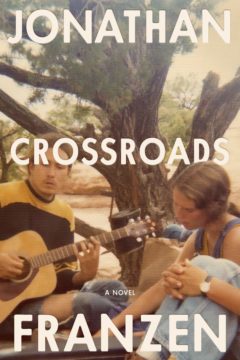

If you want to predict the future accurately, you should be an incrementalist and accept that human nature doesn’t change along most axes. Meaning that the future will look a lot like the past. If Cicero were transported from ancient Rome to our time he would easily understand most things about our society. There’d be a short-term amazement at various new technologies and societal changes, but soon Cicero would settle in and be throwing out Trump/Sulla comparisons (or contradicting them), since many of the debates we face, like what to do about growing wealth inequality, or how to keep a democracy functional, are the same as in Roman times. There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success.

There is a world, not too dissimilar from our own, in which Jonathan Franzen is a professor of creative writing at a small liberal arts college in the Midwest. He still has his bylines at the New Yorker and Harper’s (in fact, he writes for them more frequently); he still has his books (even if they’re all a bit shorter, one of them is a collection of short stories, and his translation of Spring Awakening lives with his unpublished notes on Karl Kraus in the Amish-made drawer of his ‘archive’); he still has his awards (except his NBA is now an NEA). Despite his misgivings about the effect of social media on print culture, he also has a Facebook page, which he uses to promote his readings and share photos of his outings with the local birding society, and a Twitter account, which he uses to retweet positive reviews and post about Julian Assange. Aside from his anxiety about how much time teaching and administrative duties take away from his ‘real work’ as a novelist, whether his diminishing royalty checks will be enough to cover his mortgage and his adopted son’s college tuition, and whether it would be wise to keep flirting with the sole female member of his small group of student acolytes, the greatest drama in his life occurs when he periodically becomes the main character on Twitter for saying something hopelessly out of touch – pile-ons he less-than-discreetly attributes to other writers’ envy for his hard-won success.