by Emrys Westacott

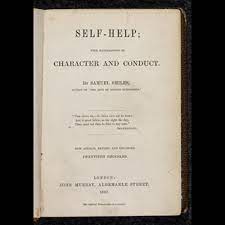

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

1859 was not a bad year for publishing in Britain. Books that came out that year included Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, and George Eliot’s Adam Bede. The first installments of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities and Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White also made their appearance. And Samuel Smiles published Self-Help.

The fiction in this list remains fairly popular. Mill’s essay is generally considered a foundational text of modern liberalism and is widely used in political science undergraduate courses. Few people other than serious historians of science read On the Origin of Species in its entirety, but its standing as one of the most important and influential works ever penned is unassailable. Self-Help, by contrast, is rarely read or referred to these day except by literary and cultural historians of the Victorian era. Yet in its day it was an immediate bestseller, was quickly translated into several languages, and established Smiles’ reputation, thereby enabling him to settle into the ranks of those who, by dint of their own efforts, had achieved success and security.

Self-help books have been around for a long time, of course. One of the purposes of Plato’s dialogues was to direct people towards living the good life for a human being. Epictetus’ Handbook offered the same promise from a Stoic perspective. Plutarch’s Lives, at least some of them, have long been taken to provide inspirational models. But in the modern era, few texts in this category have been as influential, at least in their day, as Self-Help. Perhaps its most important precursor was Ben Franklin’s Autobiography, which tells how its author rose from an impoverished nobody to a highly respected somebody, and was explicitly written to illustrate the process.

Self-Help: With Illustrations of Character, Conduct, and Perseverance, is an easy book to criticize. It consists mainly of innumerable potted biographies and anecdotes, all designed to illustrate a few recurring themes. The characters described are overwhelming white, male, and European, with a few Americans thrown in. A smug nationalism sometimes surfaces, the imperial prosperity and power of Britain being traced to certain individual virtues of the native population. No-one would describe Smiles as a great writer. He can be eloquent enough when urging his claims, but only in a fairly pedestrian way. Here is a typical sample:

Character is human nature in its best form. It is moral order embodied in the individual. Men of character are not only the conscience of society, but in every well-governed State they are its best motive power, for it is moral qualities in the main which rule the world.

The book is chock full of such edifying moral aphorisms, but like this one they are utterly conventional. Most of all, though, the book is fantastically repetitious. Hundreds of lives are summarized and incidents are recounted, all to illustrate the same few general ideas. And even then, the same people are regularly referenced (e.g. Isaac Newton, Joshua Reynolds, Robert Peel, Richard Arkwright, Robert Burns, George Stephenson) and occasionally the very same words are quoted in different chapters. A carefully wrought artistic whole it is not.

On top of all that, Self-Help has often had a press from progressives. In Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, for instance, it is dismissed as a work that teaches “ignorant, shallow-pated dolts…on their duty to their betters.”[1] And E.J. Hobsbawn describes Smiles as a “self-made journalist-publisher who hymned the virtues of capitalism.”[2] People who haven’t read it may mistakenly believe it mainly offers advice about how to “get on” in a dog-eat-dog world.

Others who were sympathetic to socialism did not share this view, however. There were reasons for this. In his essay, “Samuel Smiles and the Gospel of Work,” Asa Briggs cites a lecture by Smiles (a lecture that became the germ for Self-Help) in which he says:

[T]he education of the working classes is to be regarded, in its highest aspect, not as a means of raising up a few clever and talented men into a higher rank of life, but of elevating and improving the whole class–of raising the entire condition of the working man.

Briggs also cites the socialist Robert Blatchford (1851-1943: author of Merrie England) as saying that Self-Help was “one of the most delightful and charming books it has been my happy fortune to meet with,[3] finding it genuinely inspirational.

The fact is, to represent Self-Help as a paean to material or social success, the acquisition of wealth, or to individualism, is to misrepresent it. The main lessons it peddles on the basis of all the examples offered–and there can”t be much doubt about these since they are repeated ad nauseum–are the following:

- All work of any kind should be honoured since it all contributes to a society’s prosperity.

- Practical, hands-on experience is very often more valuable than theory or book learning.

- There is no shame in manual work.

- Many great men have raised themselves from extremely humble beginnings.

- Genius and natural talent are overrated. Even when it is necessary (e.g. Shakespeare) it is useless without great industry.

- Accidental circumstances contribute very little to the production of any great result. (Newton’s mind had to be prepared to reflect on the falling apple.)

- Good resources aren’t necessary for success. Many have succeeded with poor tools.

- The only way to achieve excellence in any field is through diligent application and perseverance.

- Mastery in any field can only be achieved slowly. This requires patience.

- In most cases, perseverance will be rewarded.

- Those who succeed are rarely motivated by money or fame but by the enjoyment they take in the process.

- Being active and working hard produces happiness; idleness leads to dissolution and despair.

- The ultimate goal of self-help should be moral character. This is far more important than anything else.

- Moral character has nothing to do with wealth, rank, or education. In this sense, anyone can be a true “gentleman.”

It’s easy to look down condescendingly on Victorian moralizing. But a few observations are worth making about this list of precepts. First, it is undoubtedly intended to be egalitarian. Every kind of work is held to deserve respect; and blood, titles, origins, property, education, even inborn ability, are considered insignificant compared to the capacity for hard work, which everyone is assumed to have in equal measure.

Second, most of the above claims still command general assent. There may be quibbles over a few of them. Some parents who live and work in the upper social echelons might not be happy if their offspring choose careers that don’t require at least a college education. Many would argue that the motivating power of money is greater than Smiles allows. For all that, you could easily insert any of these propositions into a boilerplate high school or college graduation speech today and no-one would notice since they are not especially controversial.

Nevertheless, there are potentially pernicious aspects to the self-help gospel. As Blatchford observed, when one applies it to oneself it can encourage just the sort of virtues it is meant to arouse: industriousness; diligence; perseverance; patience; etc. And these are indeed presumably qood qualities to cultivate. But they also, of course, just happen to be qualities that employers like to see in their employees. And all over the world many people work in dire conditions from which there is very little hope of escape. So while Smiles pays tribute to working people, his ethic may also contribute to their oppression.

The moral code of Self-Help can also lead us to be harsh in our judgements about people, including ourselves. Self-Help was written for a society in which social mobility had greatly increased during the preceding century. A subtextual implication of its teaching is that since self-improvement is always possible, those who fail to improve themselves have only themselves to blame. Without doubt, this became one of the pillars on which the current, widely-held belief that we live in some sort of meritocracy rests. There may often be a case for taking the “No excuses!” stance towards oneself as a way of avoiding what Jean-Paul Sartre calls “bad faith.” But applied too readily to others, it becomes a justification for withholding sympathy–and, for that matter, government assistance.

Finally, Self-Help, glorifies work for its own sake to an absurd degree. Here, Smiles was taking his lead from Thomas Carlyle whom he admired, and who preached the “gospel of work,” with no holds barred. Here is a typical–perhaps even slightly restrained!– passage from Carlyle’s Past and Present:

Blessed is he who has found his work; let him ask no other blessedness. He has a work, a life-purpose; he has found it, and will follow it! ….. Labour is Life: from the inmost heart of the Worker rises his god-given Force, the sacred celestial Life-essence breathed into him by Almighty God; from his inmost heart awakens him to all nobleness,—to all knowledge, ‘self-knowledge’ and much else……”.etc. etc.[4]

Even back then, this view of work seemed absurd to some. John Stuart Mill, for instance, rejected the idea that work had intrinsic value. Today, when thanks to ongoing technological revolutions, the prospect of most people living comfortably without having to work too hard should be easier to reach than ever, a more balanced view seems called for. Pure idleness may not be a recipe for happiness. But neither is an obsessive compulsion to put every moment to good use. As the Greeks said, “nothing to excess.”

[1] Robert Tressell, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (London: Grafton, 1987), p. 453. [Cited by Peter Sinnema in Self-Help, (Oxford), p. viii.]

[2] E. J. Hobsbawn, The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (London: Cardinal, 1989), p. 228. . [Cited by Peter Sinnema in Self-Help, (Oxford), p. viii.]

[3] Asa Briggs, Victorian People, (London: Penguin, 1954)p. 145.

[4] Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present, New York: Cornell, 1896), p. 246.