Rebecca Panovka in Harper’s:

In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.”

In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.”

This Arendt—snide, melodramatic, disdainful of the concept of factual verification—is not quite the picture that emerged after the election of Donald Trump, when she was rebranded as something of a patron saint of facts. “Welcome to the post-truth presidency,” the Washington Post opinion editor Ruth Marcus wrote, crediting Arendt as the thinker who had “presciently explained the basis for this phenomenon.” Michiko Kakutani, in an article titled the death of truth: how we gave up on facts and ended up with trump, likewise cast Arendt as a prophet whose “words increasingly sound less like a dispatch from another century than a chilling description of the political and cultural landscape we inhabit today.” how hannah arendt’s classic work on totalitarianism illuminates today’s america, ran a headline in the Washington Post. In Arendt’s work, the scholar Richard Bernstein declared in the New York Times, “we can hear not only a critique of the horrors of 20th-century totalitarianism, but also a warning about forces pervading the politics of the United States and Europe today.” The think pieces proliferated, reciting the same handful of Arendt quotations from her 1967 New Yorker essay “Truth and Politics” and her 1951 opus The Origins of Totalitarianism. Soon enough, Amazon sold out of Origins. “How could such a book speak so powerfully to our present moment?” asks a blurb at the top of its product page.

Arendt was deemed relevant when Trump was elected, relevant when he refused to wear a mask, relevant even in his defeat—with each successive crisis cast as confirmation of the predictions extrapolated from her prose.

More here.

“That all those who knew him should write about him,” Borges wrote of the protagonist Ireneo Funes in his story Funes the Memorious, “seems to me a felicitous idea.” Certainly those who knew Borges, even in passing, thought it was a felicitous idea to write about him. Fifty years ago, it seemed that a trip to Buenos Aires wasn’t complete without a stopover at his sixth-floor Calle Maipú apartment, which he shared with his mother. Both Alberto Manguel and Paul Theroux have written about reading to the blind genius in his living room. VS Naipaul, in The Return of Eva Peron, found Borges to be “curiously colonial”, insulated from the violence and disorder in his country. When Mario Vargas Llosa visited in 1981, he noticed that Borges had kept his mother’s bedroom intact, with a lilac dress ready on the bed, even though she had died six years before.

“That all those who knew him should write about him,” Borges wrote of the protagonist Ireneo Funes in his story Funes the Memorious, “seems to me a felicitous idea.” Certainly those who knew Borges, even in passing, thought it was a felicitous idea to write about him. Fifty years ago, it seemed that a trip to Buenos Aires wasn’t complete without a stopover at his sixth-floor Calle Maipú apartment, which he shared with his mother. Both Alberto Manguel and Paul Theroux have written about reading to the blind genius in his living room. VS Naipaul, in The Return of Eva Peron, found Borges to be “curiously colonial”, insulated from the violence and disorder in his country. When Mario Vargas Llosa visited in 1981, he noticed that Borges had kept his mother’s bedroom intact, with a lilac dress ready on the bed, even though she had died six years before.

Does the world need another history of the Watergate scandal? If it’s this good, yes. Michael Dobbs’s tense facto-thriller covers the first hundred days of Richard Nixon’s second administration, from the triumph of re-election to the moment when things ‘fell apart’ in mid-1973. Dobbs stalks the president around the White House, watching and listening – much like the taping system Nixon installed to protect his reputation but that, in the end, destroyed it. We hear him make bigoted comments and plot to conceal the truth, as well as lie to the faces of men he professes to love – and to himself as well.

Does the world need another history of the Watergate scandal? If it’s this good, yes. Michael Dobbs’s tense facto-thriller covers the first hundred days of Richard Nixon’s second administration, from the triumph of re-election to the moment when things ‘fell apart’ in mid-1973. Dobbs stalks the president around the White House, watching and listening – much like the taping system Nixon installed to protect his reputation but that, in the end, destroyed it. We hear him make bigoted comments and plot to conceal the truth, as well as lie to the faces of men he professes to love – and to himself as well.

Adam Tooze in the New Statesman:

Adam Tooze in the New Statesman: A

A Jinny: How do the topics of language and writing in the novel reinforce and strengthen Dagestani identity?

Jinny: How do the topics of language and writing in the novel reinforce and strengthen Dagestani identity? What makes Twitter so axiomatically hellish? It’s a place where even the most well-intentioned attempts at intellectually honest conversation inevitably devolve into misunderstanding and mutual contempt, like the fruit that crumbles into ash in the devils’ mouths in book 10 of Paradise Lost. It amplifies our simultaneous interdependency and alienation, the overtaking of meaningful political life by the triviality of the social. It is other people. But mostly Twitter is Hell because we—a “we” that, in Twitter’s universalizing idiom, outstretches optimistically or threateningly as if to envelop even those blessed souls who have never once logged on—make it so. It’s our own personal Hell, algorithmically articulated and given back to us, customized enough that I can complain to another very online friend about something that’s “all over Twitter” and he can reply, in confusion, “hmm, not my Twitter,” but shared enough that another friend can affirm, “on my Twitter too.” Pathetic fallacy subtends the most viral memes, either on the individual level (“it me”) or from the perspective of the willed collective of Twitter itself.

What makes Twitter so axiomatically hellish? It’s a place where even the most well-intentioned attempts at intellectually honest conversation inevitably devolve into misunderstanding and mutual contempt, like the fruit that crumbles into ash in the devils’ mouths in book 10 of Paradise Lost. It amplifies our simultaneous interdependency and alienation, the overtaking of meaningful political life by the triviality of the social. It is other people. But mostly Twitter is Hell because we—a “we” that, in Twitter’s universalizing idiom, outstretches optimistically or threateningly as if to envelop even those blessed souls who have never once logged on—make it so. It’s our own personal Hell, algorithmically articulated and given back to us, customized enough that I can complain to another very online friend about something that’s “all over Twitter” and he can reply, in confusion, “hmm, not my Twitter,” but shared enough that another friend can affirm, “on my Twitter too.” Pathetic fallacy subtends the most viral memes, either on the individual level (“it me”) or from the perspective of the willed collective of Twitter itself. Walter Freeman was

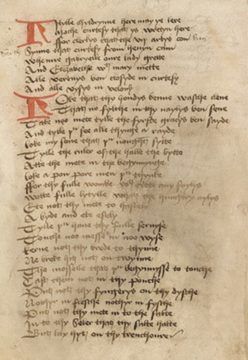

Walter Freeman was Part of the problem is that English spelling looks deceptively similar to other languages that use the same alphabet but in a much more consistent way. You can spend an afternoon familiarising yourself with the pronunciation rules of Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish and many others, and credibly read out a text in that language, even if you don’t understand it. Your pronunciation might be terrible, and the pace, stress and rhythm would be completely off, and no one would mistake you for a native speaker – but you could do it. Even French, notorious for the spelling challenges it presents learners, is consistent enough to meet the bar. There are lots of silent letters, but they’re in predictable places. French has plenty of rules, and exceptions to those rules, but they can all be listed on a reasonable number of pages.

Part of the problem is that English spelling looks deceptively similar to other languages that use the same alphabet but in a much more consistent way. You can spend an afternoon familiarising yourself with the pronunciation rules of Italian, Spanish, German, Swedish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish and many others, and credibly read out a text in that language, even if you don’t understand it. Your pronunciation might be terrible, and the pace, stress and rhythm would be completely off, and no one would mistake you for a native speaker – but you could do it. Even French, notorious for the spelling challenges it presents learners, is consistent enough to meet the bar. There are lots of silent letters, but they’re in predictable places. French has plenty of rules, and exceptions to those rules, but they can all be listed on a reasonable number of pages.

In hindsight, it was only fitting that a story about surveillance and spyware in India should have begun with more than a touch of cloak and dagger.

In hindsight, it was only fitting that a story about surveillance and spyware in India should have begun with more than a touch of cloak and dagger. In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.”

In a 1959 letter to her friend Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt paused to commiserate on a harrowing experience they had in common: having their writing fact-checked by The New Yorker. In her previous correspondence, McCarthy had mused that the magazine’s checking department was “invented by some personal Prosecutor of mine to shatter the morale,” and Arendt shared her frustration. Fact-checking, she replied, was a “kind of torture,” a “rigmarole,” and “one of the many forms in which the would-be writers persecute the writer.” Arendt’s opposition to the practice of fact-checking ran deeper than personal irritation. Throughout her work, she was critical of the infiltration of scientific terminology and methods into all aspects of human life. Couching an argument in language that sounded scientific, she thought, was a way of claiming the ability to know or predict things that could never be predicted or known. Fact-checking was a part of that larger trend: the practice, she wrote to McCarthy, was a form of “phony scientificality.” A

A