by Thomas Wells

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Climate change is such a terrifying large problem that it is hard to think sensibly about. On the one hand this makes many people prefer denial. On the other hand it can exert a warping effect on the reasoning of even those who do take it seriously. In particular, many confuse the power we have over what the lives of future generations will be like – and the moral responsibility that follows from that – with the idea that we are better off than them. These people seem to have taken the idea of the world as finite and combined it with the idea that this generation is behaving selfishly to produce a picture of us as gluttons whose overconsumption will reduce future generations to penury. But this completely misrepresents the challenge of climate change.

Here is a thought experiment that may help. Suppose you have a one-shot time machine that will take you 200 years into the past. Suppose further that Dr. Who time travel rules apply: you can change the past without paradox. If you are brave enough to make the trip, what would you take with you?

After some reflection, most people would opt for things which would be useful to people living in 1820, or useful to you if you had to live in that time. For example, technological products such as antibiotics (and the recipes to make more) and knowledge about science and history that would make you well placed to help those living then, or help you to have a very successful life amongst them.

Now consider what you would take with you if you were travelling 200 years into the future instead of into the past. Read more »

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations begins with this claim:

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018.

Helen Marden. Raja Ampat, 2018. I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him

I know someone—I’ll call him by his initials, KR—who is a Modi supporter. I have known KR for as long as I can remember. He is an intelligent, well-educated, well-travelled man. Now retired, he has a successful career behind him. He is Hindu, but he actively participated in the traditions and practices of other religions. Personally, I have great affection for him. Politically, we are now like oil and water. I usually avoid discussing politics with him because it inevitably ends in an argument: his view of Prime Minister Modi couldn’t be further from mine. In order to understand why people like him

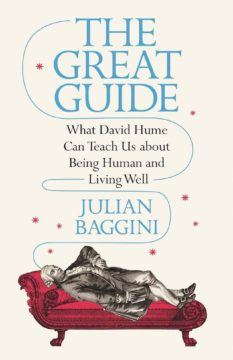

Philosophy has a vexed relationship with the business of self-help. On the one hand, philosophers offer systematic visions of how to live; on the other hand, these visions are meant to be argued with, not deferred to or chosen off the rack. Though it runs deep, this tension has not slowed the flood of titles, published in the last few years, that take a dead philosopher as a guide to life. These books will teach you How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean, and How William James Can Save Your Life; you can take The Socrates Express to Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche.

Philosophy has a vexed relationship with the business of self-help. On the one hand, philosophers offer systematic visions of how to live; on the other hand, these visions are meant to be argued with, not deferred to or chosen off the rack. Though it runs deep, this tension has not slowed the flood of titles, published in the last few years, that take a dead philosopher as a guide to life. These books will teach you How to Be a Stoic, How to Be an Epicurean, and How William James Can Save Your Life; you can take The Socrates Express to Aristotle’s Way and go Hiking with Nietzsche.

Economics is one of the better-funded and more scientific social sciences, but in some critical ways it is failing us. The main problem, as I see it, is standards: They are either too high or too low. In both cases, the result is less daring and creativity.

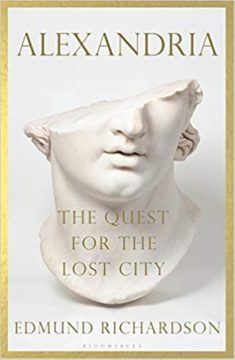

Economics is one of the better-funded and more scientific social sciences, but in some critical ways it is failing us. The main problem, as I see it, is standards: They are either too high or too low. In both cases, the result is less daring and creativity. In the hot summer of 1840, the young orientalist Henry Rawlinson arrived in Karachi and began anxiously searching for his mentor, the pioneering archaeologist of Afghanistan, Charles Masson. The rumours he had heard profoundly alarmed him.

In the hot summer of 1840, the young orientalist Henry Rawlinson arrived in Karachi and began anxiously searching for his mentor, the pioneering archaeologist of Afghanistan, Charles Masson. The rumours he had heard profoundly alarmed him. The first public literary reading I ever gave was at Manhattan’s Le Poisson Rouge for a now-defunct magazine’s issue showcase. I was 21 years old and had never read my poems in front of a live audience. More important, I had never built up the requisite nerves to read my poems aloud, and, as a way of coping, I had spent that afternoon day drinking in nearby Washington Square Park with a group of strangers from the Bronx who could have been troubadours from Kentucky. By the time I got to the venue, drunk on whiskey siphoned from their flasks and cheap beer from the local bodega, I was shocked to see that some of my friends and professional peers had shown up to watch me perform. If it wasn’t enough to want to impress them by reading at a public space, I had also trained myself to recite the poems, sans paper. Hours earlier, I had even been so bold as to crumple the printed poems and pour beer on them as a final act of humiliation. Now, in the impractically lit basement that functioned as a lounge, a bar, and a performance space, the lines of the poems melted away and the humiliation was turned inward. Once I was called up to the stage, I looked into the far recesses of the dim basement for something—call it a friendly face, call it a sign—to look back. But I saw nothing; I heard only applause and a couple glasses clink as they were placed on the bar. I put my sweaty palms inside my pocket in an attempt to dig out poems that were no longer there.

The first public literary reading I ever gave was at Manhattan’s Le Poisson Rouge for a now-defunct magazine’s issue showcase. I was 21 years old and had never read my poems in front of a live audience. More important, I had never built up the requisite nerves to read my poems aloud, and, as a way of coping, I had spent that afternoon day drinking in nearby Washington Square Park with a group of strangers from the Bronx who could have been troubadours from Kentucky. By the time I got to the venue, drunk on whiskey siphoned from their flasks and cheap beer from the local bodega, I was shocked to see that some of my friends and professional peers had shown up to watch me perform. If it wasn’t enough to want to impress them by reading at a public space, I had also trained myself to recite the poems, sans paper. Hours earlier, I had even been so bold as to crumple the printed poems and pour beer on them as a final act of humiliation. Now, in the impractically lit basement that functioned as a lounge, a bar, and a performance space, the lines of the poems melted away and the humiliation was turned inward. Once I was called up to the stage, I looked into the far recesses of the dim basement for something—call it a friendly face, call it a sign—to look back. But I saw nothing; I heard only applause and a couple glasses clink as they were placed on the bar. I put my sweaty palms inside my pocket in an attempt to dig out poems that were no longer there.