Month: April 2021

Friday Poem

Looking for a Job

What you want, at least, is the dignity

of a Sisyphus—you want to see yourself

on a hilltop, your muscles and hands

afire and chest roaring for breath, and

that boulder and its pounding descent

seen at least through your memories

of the throne. But the elevator hauls

you to another unstoried floor, another

hard carpet trod by the many, and your

one suit has a stain at the shoulder, and

you carry your account along the hallway

with the growing sense that it weighs

nothing at all. What weighs, really, is

the fear that this is your myth, this drag

up the hill with empty, tender hands,

and the ride back down again—untold

by gods or men how, during the slow

fall, you take off your suit jacket and

pick at the stain until it becomes a hole.

by David Ebenbach

from Split This Rock

Untitled

May we raise children

who love the unloved

things – the dandelion, the

worms & spiderlings.

Children who sense

the rose needs the thorn

& run into rainswept days

the same way they

turn towards sun…

And when they’re grown &

someone has to speak for those

who have no voice

may they draw upon that

wilder bond, those days of

tending tender things

and be the ones.

by Nicolette Sowder

wilderchild.com

Art by Lucy Campbell

lupiart.com

Judith Butler: Creating an Inhabitable World for Humans Means Dismantling Rigid Forms of Individuality

Judith Butler in Time:

The pandemic has illuminated and intensified racial and economic inequalities at the same time that it heightens the global sense of our obligations to one another and the earth. There is movement in a global direction, one based on a new sense of mortality and interdependency. The experience of finitude is coupled with a keen sense of inequalities: Who dies early and why, and for whom is there no infrastructural or social promise of life’s continuity?

This sense of the interdependency of the world, strengthened by a common immunological predicament, challenges the notion of ourselves as isolated individuals encased in discrete bodies, bound by established borders. Who now could deny that to be a body at all is to be bound up with other living creatures, with surfaces, and the elements, including the air that belongs to no one and everyone?

Within these pandemic times, air, water, shelter, clothing and access to health care are sites of individual and collective anxiety. But all these were already imperiled by climate change. Whether or not one is living a livable life is not only a private existential question, but an urgent economic one, incited by the life-and-death consequences of social inequality: Are there health services and shelters and clean enough water for all those who should have an equal share of this world?

More here.

“Books Do Furnish a Life” by Richard Dawkins

Daniel James Sharp in Areo:

In his previous essay collection, Science in the Soul, Richard Dawkins ponders why a scientist has never received the Nobel Prize in Literature—the only possible exception, Henri Bergson, was “more of a mystic than a true scientist”—since science, he argues, is a subject more than capable of sparking the imagination and inspiring talented penmanship: “who would deny that Carl Sagan’s writing is of Nobel literary quality, up there with the great novelists, historians, and poets? How about Loren Eiseley? Lewis Thomas? Peter Medawar? Stephen Jay Gould? Jacob Bronowski? D’Arcy Thompson?” Note Dawkins’s generosity in placing his old enemy Stephen Jay Gould on this list—and also, an understandable but glaring omission—Dawkins himself, who, in my opinion, should be at the very top.

In his previous essay collection, Science in the Soul, Richard Dawkins ponders why a scientist has never received the Nobel Prize in Literature—the only possible exception, Henri Bergson, was “more of a mystic than a true scientist”—since science, he argues, is a subject more than capable of sparking the imagination and inspiring talented penmanship: “who would deny that Carl Sagan’s writing is of Nobel literary quality, up there with the great novelists, historians, and poets? How about Loren Eiseley? Lewis Thomas? Peter Medawar? Stephen Jay Gould? Jacob Bronowski? D’Arcy Thompson?” Note Dawkins’s generosity in placing his old enemy Stephen Jay Gould on this list—and also, an understandable but glaring omission—Dawkins himself, who, in my opinion, should be at the very top.

The literary science theme is continued in his new collection, Books Do Furnish a Life, which is a sort of companion volume to Science in the Soul (both edited by Gillian Somerscales). The collection—evincing once more the author’s generosity of spirit—is mostly devoted to other peoples’ books, from scientific works to atheist memoirs, to which Dawkins has provided forewords, afterwords and other material. Also included are book reviews and transcripts of conversations with eminent writers and thinkers.

More here.

Looking at portraits with an eye to evolutionary psychology

Dan Sperber in Psyche:

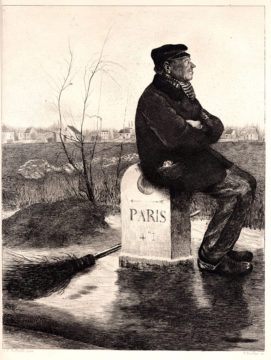

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850-1924) did his best work painting or drawing the modest inhabitants of the suburbs of Paris, where he himself lived for a time. The engraving Le Cantonnier (1881) below depicts a roadman, or a road sweeper, sitting on a milestone, his arms crossed, his broom on the ground behind him. An arrow on the milestone indicates the direction of Paris and the distance: 4.1 kilometres. Significantly, the man is facing in the opposite direction. His face is illuminated by a late-afternoon sun after a rainy day, but his expression is cheerless.

The composition of the picture is peculiar: the left half, behind the man’s back, is occupied by a meagre leafless shrub, nondescript houses in the distance, and the broom on the ground. The man sitting on the milestone occupies the right half and is facing the edge of the frame rather than its centre. This picture elicits a sense of empathy for this humble worker who seems to be enjoying his rest but to have little else to look forward to. The spatial composition of the picture contributes, I want to argue, to its poignancy, and it does so in part because of an evolved psychological disposition, a disposition that humans are likely to share with many other animals.

More here.

Pager, a nine year old Macaque, plays MindPong with his Neuralink

In Our Hurry to Conquer Nature and Death, We have Made a New Religion of Science

Jonathan Cook in Counterpunch:

Back in the 1880s, the mathematician and theologian Edwin Abbott tried to help us better understand our world by describing a very different one he called Flatland. Imagine a world that is not a sphere moving through space like our own planet, but more like a vast sheet of paper inhabited by conscious, flat geometric shapes. These shape-people can move forwards and backwards, and they can turn left and right. But they have no sense of up or down. The very idea of a tree, or a well, or a mountain makes no sense to them because they lack the concepts and experiences of height and depth. They cannot imagine, let alone describe, objects familiar to us.

Back in the 1880s, the mathematician and theologian Edwin Abbott tried to help us better understand our world by describing a very different one he called Flatland. Imagine a world that is not a sphere moving through space like our own planet, but more like a vast sheet of paper inhabited by conscious, flat geometric shapes. These shape-people can move forwards and backwards, and they can turn left and right. But they have no sense of up or down. The very idea of a tree, or a well, or a mountain makes no sense to them because they lack the concepts and experiences of height and depth. They cannot imagine, let alone describe, objects familiar to us.

In this two-dimensional world, the closest scientists can come to comprehending a third dimension are the baffling gaps in measurements that register on their most sophisticated equipment. They sense the shadows cast by a larger universe outside Flatland. The best brains infer that there must be more to the universe than can be observed but they have no way of knowing what it is they don’t know.

This sense of the the unknowable, the ineffable has been with humans since our earliest ancestors became self-conscious.

More here.

How to heal in the Anthropocene

From BBC:

In bare skin, tingling in the 8C (46F) water, Craig Foster swims into the waters off the Western Cape of South Africa and immerses himself in the Atlantic Ocean. In many ways, he is a broken man. Depleted and disconnected, he slowly dives into the all-powerful and unfriendly waters, and finds shelter in the tranquil kelp forest below – an area which he has not connected with since his childhood. As he glides through the undisturbed kelp landscape, he is overwhelmed with his smallness in this almost alien landscape. He is alone, but not for long.

In bare skin, tingling in the 8C (46F) water, Craig Foster swims into the waters off the Western Cape of South Africa and immerses himself in the Atlantic Ocean. In many ways, he is a broken man. Depleted and disconnected, he slowly dives into the all-powerful and unfriendly waters, and finds shelter in the tranquil kelp forest below – an area which he has not connected with since his childhood. As he glides through the undisturbed kelp landscape, he is overwhelmed with his smallness in this almost alien landscape. He is alone, but not for long.

Meandering through the tangled kelp terrain equipped with curiosity and a camera, Foster takes us through his moving story of healing in the hit Netflix documentary My Octopus Teacher. Soon, he has his first sighting of a strange spectacle: a moving conglobulation of shells. Then, suddenly, an octopus emerges and retreats into the kelp. This is Foster’s first encounter of the octopus that serendipitously teaches him, over the next few months, about purposeful and deep connection. As he dives deeper into this unlikely relationship, Foster immerses himself in the natural world, getting to know the subtleties of the wild and his place in it, which eventually sets him free. This is healing.

As humans, we face diverse experiences and pressures that require healing. And as a new epoch is unfolding – the Anthropocene – deep planetary changes and environmental destruction are necessitating healing at individual, community and global scales. Feelings of pain, suffering, fear, anger and grief for those directly affected by climate change or those watching through TV screens are real. From the Inuit in Canada to Australian farmers and island nations, ecological grief and anxiety have been recorded across the world.

More here.

Thursday Poem

“The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name. The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth. The named is the mother of ten thousand things.” —Lao Tzu in The Tao Te Ching

73

Morning is breaking. No; morning isn’t breaking.

Morning is an abstract thing, it exists, but is not a thing.

Here, at this hour, we’re beginning to see the sun.

If the morning light on the trees is beautiful,

It’s just as beautiful whether we call the morning “beginning to

see the sun”

As it is if we call it “the morning”;

That’s why there’s no advantage in giving things the wrong name,

Or indeed giving them names at all.

by Fernando Pessoa

from The Complete Works of Alberta Caeiro

New Direction Paperbooks, 2020

translation: Margaret Jull Costa & Patricio Ferrari

This Rare Spirit: A Life of Charlotte Mew

Joanna Kavenna at Literary Review:

Mew’s poems range from conventional Victorian elegies to wild outpourings of loss, longing and fear of death. If you read her work to a random array of people who don’t know it (as I did the other day) then they may well liken it to Christina Rossetti, Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence or (unkindly) ‘bad Philip Larkin’. Her most memorable and idiosyncratic poems include ‘Rooms’ (‘I remember rooms that have had their part/In the steady slowing down of the heart’) and ‘Fame’ (‘Sometimes in the over-heated house, but not for long,/Smirking and speaking rather loud,/ I see myself among the crowd’). Her work, writes Copus, was ‘unashamedly emotive’ and therefore ‘out of kilter with the ideals of the fashionable Imagists’. She was too traditional for some and too radical for others. A printer refused to set one of her poems, ‘Madeleine in Church’, because he thought it was blasphemous. She has ‘frequently been identified as a lesbian’, Copus notes, including by Penelope Fitzgerald in Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (1984). There is also a rumour that Mew ‘conducted an illicit affair with Thomas Hardy’.

Mew’s poems range from conventional Victorian elegies to wild outpourings of loss, longing and fear of death. If you read her work to a random array of people who don’t know it (as I did the other day) then they may well liken it to Christina Rossetti, Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence or (unkindly) ‘bad Philip Larkin’. Her most memorable and idiosyncratic poems include ‘Rooms’ (‘I remember rooms that have had their part/In the steady slowing down of the heart’) and ‘Fame’ (‘Sometimes in the over-heated house, but not for long,/Smirking and speaking rather loud,/ I see myself among the crowd’). Her work, writes Copus, was ‘unashamedly emotive’ and therefore ‘out of kilter with the ideals of the fashionable Imagists’. She was too traditional for some and too radical for others. A printer refused to set one of her poems, ‘Madeleine in Church’, because he thought it was blasphemous. She has ‘frequently been identified as a lesbian’, Copus notes, including by Penelope Fitzgerald in Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (1984). There is also a rumour that Mew ‘conducted an illicit affair with Thomas Hardy’.

more here.

Hooked: Art and Attachment

Nell Osborne at Review 31:

In 2015, in The Limits of Critique, Rita Felski argued that critique, a term she uses to characterise the predominant institutionalised practices of interpretation, solicits the critic to adopt a stance and tone of ‘ferocious and blistering detachment’. The critic’s encounter with a text is driven by ‘desire to puncture illusions, topple idols and destroy divinities,’ that is both combative and paranoid. Towards the end of this book, Felski invokes Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as one possible way out from the uncomfortable corner that critique has backed us into. Felski’s 2020 book, Hooked: Art and Attachment, returns to this possibility: to demonstrate an intellectual and political alternative to the method of ‘critical reading’. This book extends Felski’s belief that criticism cannot fully account for broader questions of attachment: ‘What do works of art do? What do they set in motion? And to what are they linked or tie?’ Here, as elsewhere, one of Felski’s most convincing claims is that aesthetic relations always involve ‘more than power relations’.

In 2015, in The Limits of Critique, Rita Felski argued that critique, a term she uses to characterise the predominant institutionalised practices of interpretation, solicits the critic to adopt a stance and tone of ‘ferocious and blistering detachment’. The critic’s encounter with a text is driven by ‘desire to puncture illusions, topple idols and destroy divinities,’ that is both combative and paranoid. Towards the end of this book, Felski invokes Actor-Network Theory (ANT) as one possible way out from the uncomfortable corner that critique has backed us into. Felski’s 2020 book, Hooked: Art and Attachment, returns to this possibility: to demonstrate an intellectual and political alternative to the method of ‘critical reading’. This book extends Felski’s belief that criticism cannot fully account for broader questions of attachment: ‘What do works of art do? What do they set in motion? And to what are they linked or tie?’ Here, as elsewhere, one of Felski’s most convincing claims is that aesthetic relations always involve ‘more than power relations’.

more here.

Clark Lectures 2021: Rita Felski

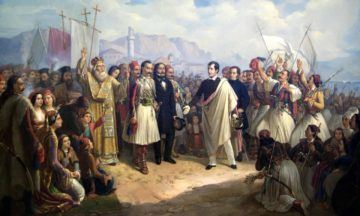

Lord Byron’s £4,000 cheque that helped create modern Greece

Helena Smith in The Guardian:

Racked by fever, prone to fits of delirium, consumed by his last great passion – the liberation of Greece – Lord Byron lay on his sickbed. It was 18 April 1824. The great Romantic poet would be dead the next day.

Racked by fever, prone to fits of delirium, consumed by his last great passion – the liberation of Greece – Lord Byron lay on his sickbed. It was 18 April 1824. The great Romantic poet would be dead the next day.

“I have given her [Greece] my time, my means, my health,” he is recorded as saying in a moment of lucidity. “And now I give her my life! What could I do more?”

Byron’s death in Missolonghi, the malaria-ridden town where he had spearheaded the Greeks’ revolt against Ottoman rule, induced instant shock, convulsing the English-speaking world.

The man who was “mad, bad and dangerous to know”, a celebrity of his day who was loved and loathed in equal measure, had spent a mere 100 days in the land whose freedom he had championed so vociferously.

More here.

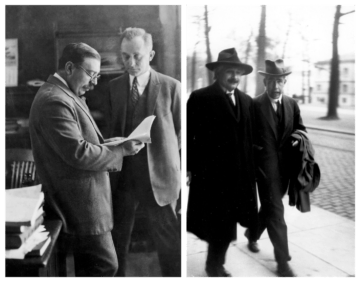

When Norbert Wiener met Albert Einstein

Jørgen Veisdal in Cantor’s Paradise:

Letter from Norbert to Bertha Wiener (July, 1925):

Letter from Norbert to Bertha Wiener (July, 1925):

There was a nice Swiss student from the Dresdner Technische Hochschule on the train from Leipzig. He talked very good English, and we had an animated conversation in both languages. We breakfasted together in the dining car leaving Frankfurt. At a nearby table I saw a strangely familiar face, and remarked to my comrade “I’ll eat my hat if that isn’t Einstein!”

After breakfast I decided (in view of his friendship with Lichtenstein, of my profession, and of the fact that I had been introduced to him in the States) to look him up.

I found him in a third-class compartment, and it was Einstein after all. When I said I was a mathematician, he began quizzing me about my line. He was quite impressed by my new light stuff. He then began telling me of his reduction of gravitation and the Maxwell equations to a single minimization problem. This is brand new stuff — its not out yet, and he only wrote it three weeks ago.

More here.

Meeting Adam Smith

Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

Like many readers, I began in early adulthood to keep a mental list of big books that I meant to tackle someday. Thanks to the passage of time and my dilatory nature, that list now includes some entries that I haven’t gotten around to for many years—in a few cases, a decade or more. One such book is Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), which I decided to read back in graduate school after taking a course that featured Smith’s earlier achievement, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). At the time, though, the book seemed just a bit too long, and every time I’ve picked it up since I’ve always been able to manufacture reasons for further delay.

Like many readers, I began in early adulthood to keep a mental list of big books that I meant to tackle someday. Thanks to the passage of time and my dilatory nature, that list now includes some entries that I haven’t gotten around to for many years—in a few cases, a decade or more. One such book is Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), which I decided to read back in graduate school after taking a course that featured Smith’s earlier achievement, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). At the time, though, the book seemed just a bit too long, and every time I’ve picked it up since I’ve always been able to manufacture reasons for further delay.

Having just read a biography of Smith and reread Theory of Moral Sentiments in January, I decided that it was truly now or never. And while I recognized that Wealth of Nations would be no War and Peace, I wondered if any pleasures might await in a book that Smith’s contemporaries immediately proclaimed a masterpiece.

More here.

George Will and Steven Pinker on Liberalism

Brockhampton Makes Good on Its Supergroup Promise

Sheldon Pearce at The New Yorker:

In the years since the trailblazers of Odd Future distributed their music through Tumblr, many younger artists have used the social Web to find kindred creative spirits—both around the world and closer to home. The YBN hip-hop collective started in XBox Live group chats, and key members of the Bay Area group AG Club stumbled upon one another on Twitter. At the center of this movement is Brockhampton, a huge, perception-bending group with origins in Texas and branches as far off as Grenada and Belfast. The collective, conceived on a message board by its de-facto leader, the polymath Kevin Abstract, eventually ballooned to include more than a dozen rappers, singers, producers, and visual artists of various races, sexual orientations, and creative philosophies. The bohemian crew—which mixes Abstract’s high-school friends (JOBA, Merlyn Wood, and Matt Champion) with those he met online (bearface, Dom McLennon, Jabari Manwa, and Romil Hemnani)—set out to remake a pop paradigm, the boy band, in a way that reflected itself: multiracial, multinational, other.

In the years since the trailblazers of Odd Future distributed their music through Tumblr, many younger artists have used the social Web to find kindred creative spirits—both around the world and closer to home. The YBN hip-hop collective started in XBox Live group chats, and key members of the Bay Area group AG Club stumbled upon one another on Twitter. At the center of this movement is Brockhampton, a huge, perception-bending group with origins in Texas and branches as far off as Grenada and Belfast. The collective, conceived on a message board by its de-facto leader, the polymath Kevin Abstract, eventually ballooned to include more than a dozen rappers, singers, producers, and visual artists of various races, sexual orientations, and creative philosophies. The bohemian crew—which mixes Abstract’s high-school friends (JOBA, Merlyn Wood, and Matt Champion) with those he met online (bearface, Dom McLennon, Jabari Manwa, and Romil Hemnani)—set out to remake a pop paradigm, the boy band, in a way that reflected itself: multiracial, multinational, other.

It has largely succeeded: since 2014, Brockhampton has created fascinating composite songs that blow up rap into opera and reconfigure pop to be more representative of the sounds found online.

more here.

Buzzcut – Brockhampton (feat. Danny Brown)

A Possible Way Forward In An Age Of Institutional Fragmentation

Alan Jacobs at The Hedgehog Review:

The Distributists of a century ago, like their great predecessors John Ruskin and William Morris, were aware of the danger that a subsidiarist devolution into smallholdings could have an atomizing effect on society. They thought that one means by which to counteract this tendency was to encourage the renewal of the ancient guild system. The best-known exponent of this idea was Arthur Penty, who in 1906 published a book called The Restoration of the Guild System. (Excerpt here, full text here.) Penty thought that the then-rising trade union movement could lay the foundation for a new set of guilds—one of many examples of the ways in which it can be difficult to label these alternative economic orders as either Left or Right in political orientation. The best-known example of an anarcho-syndicalist system, the Mondragon Corporation in the Basque region of Spain, was founded by a Catholic priest, José María Arizmendiarrieta, whose intellectual sources were much the same as those of the famously right-wing Chesterton and Belloc.

The Distributists of a century ago, like their great predecessors John Ruskin and William Morris, were aware of the danger that a subsidiarist devolution into smallholdings could have an atomizing effect on society. They thought that one means by which to counteract this tendency was to encourage the renewal of the ancient guild system. The best-known exponent of this idea was Arthur Penty, who in 1906 published a book called The Restoration of the Guild System. (Excerpt here, full text here.) Penty thought that the then-rising trade union movement could lay the foundation for a new set of guilds—one of many examples of the ways in which it can be difficult to label these alternative economic orders as either Left or Right in political orientation. The best-known example of an anarcho-syndicalist system, the Mondragon Corporation in the Basque region of Spain, was founded by a Catholic priest, José María Arizmendiarrieta, whose intellectual sources were much the same as those of the famously right-wing Chesterton and Belloc.

more here.