by Michael Liss

There was a time when we had no political parties.

It was brief, like the glow of a firefly on a warm late summer evening, but it occurred. There were no political parties at the time of the American Revolution, or when the newly freed colonies joined in the Articles of Confederation. None at the time they went to Philadelphia to hammer out the Constitution, and none when it was ratified (although the supporters of it were called Federalists and Alexander Hamilton eventually organized them as a party). For the first three years of the new government, until May of 1792, when Thomas Jefferson and James Madison founded the Democratic-Republican Party, the Federalists were the only political party in the land.

When we 21st Century Americans, out of desperation, look to the Constitution for a way out of intractable and pernicious partisanship, we often look in vain for the answers because they really aren’t there. The Constitution was not intentionally designed to compensate for party-based partisanship. Rather, it was a balancing act between regional forces, between economic interests, between small and big states, between slave and free, and between political philosophies. The Framers needed to find enough compromises to get the states to agree to the new framework. No interest got everything, but all got something, because they had to. Why join otherwise?

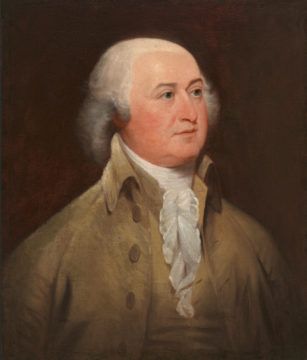

Obviously, the Framers were aware of political parties (England’s Parliament had its Whigs and Tories). They were also aware of the dangers of partisanship (most notably, Madison in Federalist No. 10). But they hadn’t yet made the leap to only negotiating governance through the synthetic framework of a multiparty system, nor to the idea of candidates for Chief Executive differentiating themselves by party identification. The model for a President was in front of everyone—George Washington. Read more »

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020.

ET Trigg. I Can’t Breathe, 2020. “Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136).

“Why, during the seventeenth century, did people who knew all the arguments that there is a God stop finding God’s reality intuitively obvious?” This, says Alec Ryrie in his Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt (2019), is the heart of the question of early modern unbelief (136). On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

On Saturday, April 10, 2021, in Fribourg in the west of Switzerland, Besuch der Lieder, the troupe of musicians with whom

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

They call it the Sargasso, this grass. It is the bane of Belize, an invasive floating weed that keeps pitchforks flailing along the waterfront. The Sargasso Sea, we know where that is. But this grass is from Brazil, Réné says. It’s a new challenge from a new place. It isn’t challenge enough just to weather a pandemic, he says. Now there’s this, too.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary.

That is, we had to talk about it. I thought of a musician as someone who made a living performing music. I didn’t do that. To be sure, I made some money playing around town in a rock band and I’d spent years learning the trumpet. I’d marched in parades and at football games; I’d played concerts with various groups. But I wasn’t a full-time, you know, a professional musician, a real musician. Gren insisted that I was a musician because I played music, a lot, and was committed to it. That’s all that’s necessary. Podcast time!

Podcast time!

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant.

They are invisible at first. In their Southeast Asian forest homes, they grow as thin strands of cells, foreign fibers sometimes more than 10 meters long that weave through the vital tissues of their vine hosts, siphoning nourishment from them. Even under a microscope, the single-file lines of cells are nearly indistinguishable from the vine’s own. They seem more like a fungus than a plant. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is not likely to make humans redundant. Nor will it  Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic.

Postcolonial literature brings together writings from formerly colonised territories, allowing commonalities across disparate cultures to be identified and examined. Here, the University of Toronto academic Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb recommends five key works that explore philosophical and political questions through allegory, personal reflection and powerful polemic. In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.”

In high school, one of author Jess Zimmerman’s Internet usernames was Medusa. A self-described mythology nerd, her childhood copy of “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” was well-worn. But as she recalls in her scorching collection of essays, “Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology,” she particularly identified with the snake-haired creature whose power originated in ugliness: The mere sight of Medusa could turn a man to stone. As a teenager who was profoundly insecure about her looks, Zimmerman writes that calling herself Medusa was “an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost.” The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic

The pandemic is sweeping through India at a pace that has staggered scientists. Daily case numbers have exploded since early March: the government reported 273,810 new infections nationally on 18 April. High numbers in India have also helped drive global cases to a daily high of 854,855 in the past week, almost breaking a record set in January. Just months earlier, antibody data had suggested that many people in cities such as Delhi and Chennai had already been infected, leading some researchers to conclude that the worst of the pandemic