Thomas Bird at the BBC:

The creature stretched, then clung upright against the tree with its sharp claws and began to groom. Its skin required some attention as it had, frankly, a lot of it. A membrane stretched from its neck via its hands and feet to its tail, a kite-like feature that distinguishes the colugo, once popularly known as the flying lemur, from other night gliders like the flying squirrel, which has a long tail that it uses to fan itself through the air. Because they don’t fly, nor use a tail to fan, colugos, with the logic of a hand glider launching from a hillside, typically climb high into a tree before attempting to glide. Still, their range is impressive. According to Miard they’ve been recorded gliding a full 150m, although hops of 30m or less are far more common.

The creature stretched, then clung upright against the tree with its sharp claws and began to groom. Its skin required some attention as it had, frankly, a lot of it. A membrane stretched from its neck via its hands and feet to its tail, a kite-like feature that distinguishes the colugo, once popularly known as the flying lemur, from other night gliders like the flying squirrel, which has a long tail that it uses to fan itself through the air. Because they don’t fly, nor use a tail to fan, colugos, with the logic of a hand glider launching from a hillside, typically climb high into a tree before attempting to glide. Still, their range is impressive. According to Miard they’ve been recorded gliding a full 150m, although hops of 30m or less are far more common.

More here.

The Treaty of Versailles—a contract that changed the course of the century and beyond—has been all but forgotten in the public sphere and in popular discourse. As a result, few people think about the world we live in as being made by the Treaty. In fact, most don’t think about it at all.

The Treaty of Versailles—a contract that changed the course of the century and beyond—has been all but forgotten in the public sphere and in popular discourse. As a result, few people think about the world we live in as being made by the Treaty. In fact, most don’t think about it at all. Like many women in their 30s, I feel a certain nostalgic connection to Britney Spears. In high school, I remember watching her dizzying rise as America’s golden girl. Then came her public struggles and searing battering by the paparazzi and tabloids while I was in my early 20s. I have also felt a fascination with her unusual

Like many women in their 30s, I feel a certain nostalgic connection to Britney Spears. In high school, I remember watching her dizzying rise as America’s golden girl. Then came her public struggles and searing battering by the paparazzi and tabloids while I was in my early 20s. I have also felt a fascination with her unusual  What she was up against were, in short, warnings. These were most explicit each Lent and Easter. In April 1932, Eliot said he had gained so much that he could not give up his journey towards what he termed “reality”: as he put it in the Quartets, “human kind / Cannot bear very much reality.” The real thing lay beyond life, and he could no longer accept the kind of love that would mean giving that up. If he were to rank his two narratives, the supernatural did come first. Desire was evil, he believed, and talking to Hale more frankly than to anyone, he explained how difficult it was to fight this evil when he woke in the morning. When she notes his diminished expressiveness in the spring and summer of 1932, he explains this as a strategy, inseparable from unsatisfied desire. His typewriter stumbles, he crosses out and picks up the thought again with more deliberation, putting companionship before passion, then dependence, reverence and a protective instinct. He decides to label his feeling for her “respect.” True enough, though only one strand. He was not so earnest that he did not sometimes fix on her bathing costume and wavy hair.

What she was up against were, in short, warnings. These were most explicit each Lent and Easter. In April 1932, Eliot said he had gained so much that he could not give up his journey towards what he termed “reality”: as he put it in the Quartets, “human kind / Cannot bear very much reality.” The real thing lay beyond life, and he could no longer accept the kind of love that would mean giving that up. If he were to rank his two narratives, the supernatural did come first. Desire was evil, he believed, and talking to Hale more frankly than to anyone, he explained how difficult it was to fight this evil when he woke in the morning. When she notes his diminished expressiveness in the spring and summer of 1932, he explains this as a strategy, inseparable from unsatisfied desire. His typewriter stumbles, he crosses out and picks up the thought again with more deliberation, putting companionship before passion, then dependence, reverence and a protective instinct. He decides to label his feeling for her “respect.” True enough, though only one strand. He was not so earnest that he did not sometimes fix on her bathing costume and wavy hair.

What is racial fraud and how is it possible? The answer would be clear enough, perhaps, if race were a biological reality. But the consensus seems to be that race is a social construction, a product of human ingenuity. So why can’t you choose to be any race you want?

What is racial fraud and how is it possible? The answer would be clear enough, perhaps, if race were a biological reality. But the consensus seems to be that race is a social construction, a product of human ingenuity. So why can’t you choose to be any race you want? Of course I stole the title for this talk from George Orwell. One reason I stole it was that I like the sound of the words: Why I Write. There you have three short unambiguous words that share a sound, and the sound they share is this:

Of course I stole the title for this talk from George Orwell. One reason I stole it was that I like the sound of the words: Why I Write. There you have three short unambiguous words that share a sound, and the sound they share is this: In January 2017, a lengthy proposal showed up at the offices of the

In January 2017, a lengthy proposal showed up at the offices of the  Have you ever felt uncomfortable sharing your opinion on politics — whether online or with friends? If so, you’re not alone. Americans are becoming increasingly cautious about sharing their political opinions. In a recent

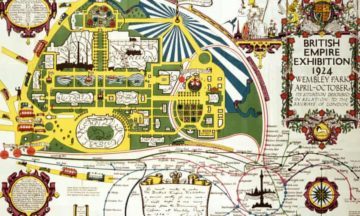

Have you ever felt uncomfortable sharing your opinion on politics — whether online or with friends? If so, you’re not alone. Americans are becoming increasingly cautious about sharing their political opinions. In a recent  In the endless catalogue of British imperial atrocities, the unprovoked invasion of Tibet in 1903 was a minor but fairly typical episode. Tibetans, explained the expedition’s cultural expert, were savages, “more like hideous gnomes than human beings”. Thousands of them were massacred defending their homeland, “knocked over like skittles” by the invaders’ state-of-the-art machine guns. “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire,” wrote a British lieutenant, “though the General’s order was to make as big a bag as possible.” As big a bag as possible – killing inferior people was a kind of blood sport.

In the endless catalogue of British imperial atrocities, the unprovoked invasion of Tibet in 1903 was a minor but fairly typical episode. Tibetans, explained the expedition’s cultural expert, were savages, “more like hideous gnomes than human beings”. Thousands of them were massacred defending their homeland, “knocked over like skittles” by the invaders’ state-of-the-art machine guns. “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire,” wrote a British lieutenant, “though the General’s order was to make as big a bag as possible.” As big a bag as possible – killing inferior people was a kind of blood sport. By his own lights, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, was

By his own lights, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, ambassador, senator, sociologist, and itinerant American intellectual, was  T

T Back outside in the summer air, the summer frost heaves passed beneath my feet. I thought of Robert Walser, his little essay on walking, seeing everything afresh, the teeming world, the sap running, the beautiful phenomena, or his essay about Kleist walking around Thun, the mountainous Swiss village—“Bells are ringing. The people are leaving the hilltop church.” In those days, Walser wrote most of his stories in a micro-script so tiny it was assumed illegible for years, until two scholars with a magnifying lens revealed that the script, which looked like termite tracks, was actually Kurrent, a form of handwriting, medieval in origin, used by German speakers until the mid-twentieth century. Why am I describing Walser? Because I thought of him as I was walking on the sidewalk. Because Sontag describes Walser’s writing as a free fall of innocuous observations not governed by plot, in which “the important is redeemed as a species of the unimportant.” For instance, he ends the story “Autumn (II)” with the sentence, “In the city where I reside, a van Gogh exhibition is currently on view,” apropos of nothing. We don’t know what the broken white line means until much later. That’s why dream journalists write. That’s why journalists dream.

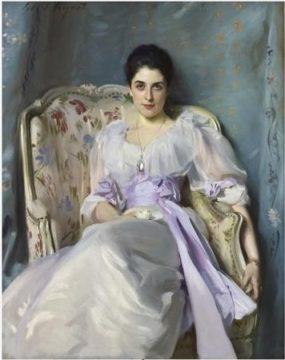

Back outside in the summer air, the summer frost heaves passed beneath my feet. I thought of Robert Walser, his little essay on walking, seeing everything afresh, the teeming world, the sap running, the beautiful phenomena, or his essay about Kleist walking around Thun, the mountainous Swiss village—“Bells are ringing. The people are leaving the hilltop church.” In those days, Walser wrote most of his stories in a micro-script so tiny it was assumed illegible for years, until two scholars with a magnifying lens revealed that the script, which looked like termite tracks, was actually Kurrent, a form of handwriting, medieval in origin, used by German speakers until the mid-twentieth century. Why am I describing Walser? Because I thought of him as I was walking on the sidewalk. Because Sontag describes Walser’s writing as a free fall of innocuous observations not governed by plot, in which “the important is redeemed as a species of the unimportant.” For instance, he ends the story “Autumn (II)” with the sentence, “In the city where I reside, a van Gogh exhibition is currently on view,” apropos of nothing. We don’t know what the broken white line means until much later. That’s why dream journalists write. That’s why journalists dream. It was often the case in the late 19th century that if you wanted to add a little prestige to your life you had your portrait painted by a notable portrait painter. Or you had your family painted, or just your wife. This latter idea was the thought that occurred to Sir Andrew Agnew, the 9th Baronet of Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. He was proud of his wife, perhaps in the way one is proud of a horse, or an elegant piece of furniture. He wanted others to be proud too. There was a lot of pride going around.

It was often the case in the late 19th century that if you wanted to add a little prestige to your life you had your portrait painted by a notable portrait painter. Or you had your family painted, or just your wife. This latter idea was the thought that occurred to Sir Andrew Agnew, the 9th Baronet of Lochnaw Castle in Wigtownshire, Scotland. He was proud of his wife, perhaps in the way one is proud of a horse, or an elegant piece of furniture. He wanted others to be proud too. There was a lot of pride going around.