Sophie McBain in New Spectator:

In the mid-Sixties the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created the first artificial intelligence chatbot, named Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle. Eliza was programmed to respond to users in the manner of a Rogerian therapist – reflecting their responses back to them or asking general, open-ended questions. “Tell me more,” Eliza might say. Weizenbaum was alarmed by how rapidly users grew attached to Eliza. “Extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” he wrote. It disturbed him that humans were so easily manipulated.

In the mid-Sixties the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum created the first artificial intelligence chatbot, named Eliza, after Eliza Doolittle. Eliza was programmed to respond to users in the manner of a Rogerian therapist – reflecting their responses back to them or asking general, open-ended questions. “Tell me more,” Eliza might say. Weizenbaum was alarmed by how rapidly users grew attached to Eliza. “Extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people,” he wrote. It disturbed him that humans were so easily manipulated.

From another perspective, the idea that people seem comfortable offloading their troubles not on to a sympathetic human, but a sympathetic-sounding computer program, might present an opportunity. Even before the pandemic, there were not enough mental health professionals to meet demand. In the UK, there are 7.6 psychiatrists per 100,000 people; in some low-income countries, the average is 0.1 per 100,000. “The hope is that chatbots could fill a gap, where there aren’t enough humans,” Adam Miner, an instructor at the department of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at Stanford University, told me. “But as we know from any human conversation, language is complicated.”

Alongside two colleagues from Stanford, Miner was involved in a recent study that invited college students to talk about their emotions via an online chat with either a person or a “chatbot” (in reality, the chatbot was operated by a person rather than AI).

More here.

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen

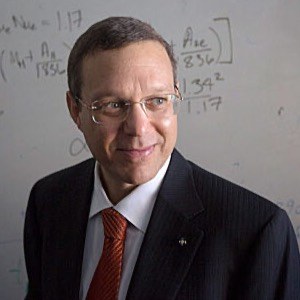

As long as vaccines have existed, humans have been suspicious of both the shots and those who administer them. The first inoculation deployed in America, against smallpox in the 1720s, was decried as antithetical to God’s will. An outraged citizen  For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology.

For 7 years as president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Robert Tjian helped steer hundreds of millions of dollars to scientists probing provocative ideas that might transform biology and biomedicine. So the biochemist was intrigued a couple of years ago when his graduate student David McSwiggen uncovered data likely to fuel excitement about a process called phase separation, already one of the hottest concepts in cell biology. To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people.

To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people. Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at

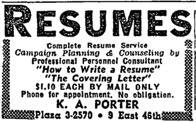

Imagine bits of wood trapped in eddies of a stream, going round and round atop the waters that flow beneath them. The image comes to mind in response to a surprising show—surprisingly great, contrary to my skeptical expectation—at  For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads.

For as long as we have been writing cover letters, or covering letters, and whatever preceded covering letters, writers have sought the support of those who have mastered the craft du jour. Lurie describes what he believes is the earliest example of an advertisement for how-to guides on writing “cover letters.” He says, “The first true sign that cover letters were mainstream enough to cause job applicants some anxiety was an advertisement in 1965, in the Boston Globe.” Again, it should come as no surprise, that one will find an advertisement for a how-to guide on “the covering letter” (again in the New York Times) in August 1955—more than a decade before the example that Mr. Lurie cites in the Boston Globe, and indeed much closer to the pair of Dutch Boy ads. One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk.

One relevant fact is that people over 65 have a higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than younger people do, and those over 75 are at even higher risk. The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper

The possible existence of technologically advanced extraterrestrial civilizations — not just alien microbes, but cultures as advanced (or much more) than our own — is one of the most provocative questions in modern science. So provocative that it’s difficult to talk about the idea in a rational, dispassionate way; there are those who loudly insist that the probability of advanced alien cultures existing is essentially one, even without direct evidence, and others are so exhausted by overblown claims in popular media that they want to squelch any such talk. Astronomer Avi Loeb thinks we should be taking this possibility seriously, so much so that he suggested that the recent interstellar interloper  Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re

Our differences over policy are substantial, but they’re  I

I  JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were

JERUSALEM — Israel, which leads the world in vaccinating its population against the coronavirus, has produced some encouraging news: Early results show a significant drop in infection after just one shot of a two-dose vaccine, and better than expected results after both doses. Public health experts caution that the data, based on the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is preliminary and has not been subjected to clinical trials. Even so, Dr. Anat Ekka Zohar, vice president of Maccabi Health Services, one of the Israeli health maintenance organizations that released the data, called it “very encouraging.” In the first early report, Clalit, Israel’s largest health fund, compared 200,000 people aged 60 or over who received a first dose of the vaccine to a matched group of 200,000 who had not been vaccinated yet. It said that 14 to 18 days after their shots, the partially vaccinated patients were  Didion, now eighty-six, has been an object of fascination ever since, boosted by the black-lace renaissance she experienced after publishing “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), her raw and ruminative account of the months following Dunne’s sudden death. Generally, writers who hold readers’ imaginations across decades do so because there’s something unsolved in their project, something that doesn’t square and thus seems subject to the realm of magic. In Didion’s case, a disconnect appears between the jobber-like shape of her writing life—a shape she often emphasizes in descriptions of her working habits—and the forms that emerged as the work accrued. For all her success, Didion was seventy before she finished a nonfiction book that was not drawn from newsstand-magazine assignments. She and Dunne started doing that work with an eye to covering the bills, and then a little more. (Their Post rates allowed them to rent a tumbledown Hollywood mansion, buy a banana-colored Corvette Stingray, raise a child, and dine well.) And yet the mosaic-like nonfiction books that Didion produced are the opposite of jobber books, or market-pitched books, or even useful, fibrous, admirably executed books. These are strange books, unusually shaped. They changed the way that journalistic storytelling and analysis were done.

Didion, now eighty-six, has been an object of fascination ever since, boosted by the black-lace renaissance she experienced after publishing “The Year of Magical Thinking” (2005), her raw and ruminative account of the months following Dunne’s sudden death. Generally, writers who hold readers’ imaginations across decades do so because there’s something unsolved in their project, something that doesn’t square and thus seems subject to the realm of magic. In Didion’s case, a disconnect appears between the jobber-like shape of her writing life—a shape she often emphasizes in descriptions of her working habits—and the forms that emerged as the work accrued. For all her success, Didion was seventy before she finished a nonfiction book that was not drawn from newsstand-magazine assignments. She and Dunne started doing that work with an eye to covering the bills, and then a little more. (Their Post rates allowed them to rent a tumbledown Hollywood mansion, buy a banana-colored Corvette Stingray, raise a child, and dine well.) And yet the mosaic-like nonfiction books that Didion produced are the opposite of jobber books, or market-pitched books, or even useful, fibrous, admirably executed books. These are strange books, unusually shaped. They changed the way that journalistic storytelling and analysis were done. SM

SM  Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.

Do you have a right to own a microwave oven? To be clear, ideally in a free society, absent a clear showing of harm to others, there’s a presumption that you can do whatever you want and own whatever you can make or buy. So, you do have a basic right to own things – to acquire property, as political philosophers like to say. But it’s consistent with that right for there to be a lot of rules and regulations around what you can own – and even prohibitions on owning certain kinds of things.