by Jackson Arn

Slurs have a way of mellowing into labels. History is full of Yankees and Cockneys, Methodists and Jesuits, Whigs and Tories, who steal a term of abuse and apply it to themselves as an act of sardonic revenge. Sometimes the tactic works too well, and people forget that the word was ever tainted. And sometimes the definition changes so many times people lose count, and the word is left to drag a muddle of meanings behind it.

“System” is such a word. Its DNA is full of recessive genes ready to reappear in the next generation. It suggests the banal and the sinister equally, a low, humming scientism and a hiss of danger. Politicians use it with both connotations in mind, sometimes both at once. Immigrants, trans activists, thwarted unionists are advised to have faith in the system, even as other politicians mock them for gaming it—can the two systems really be the same? Political science majors, not yet disillusioned, dream about the day they’ll change the system from within. In 1969, Bill Clinton, 23 years old and already impatiently waiting to be president, wrote, “I decided to accept the draft in spite of my beliefs for one reason: to maintain my political viability within the system.” Today, everyone seems to agree that the system, whatever it might be, is rigged. The word’s ambiguity is its longevity.

From the Greek: sun, meaning “with,” and histanal, meaning “set up, stand”—thus, a whole made out of parts, standing together. Which parts, and why they stand together, is left unclear—an ambiguity the rest of the sentence is supposed to correct but rarely does. This ambiguity is a part of the modern condition, since modernity depends on systems. Systems, rather than deities or monarchs, keep us safe: systems, for which individual parts are important but never all-important; systems, whose purpose, by definition, cannot be found in any single one of these parts.

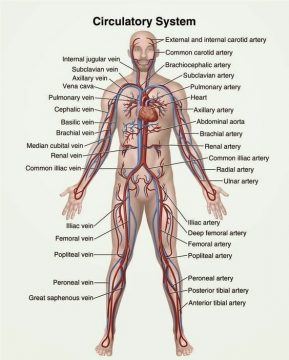

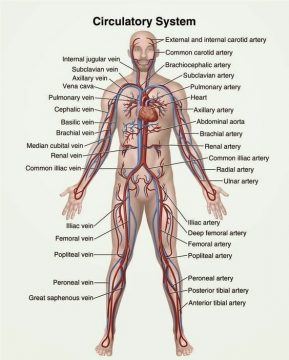

Modernity is supposed to be an age of science, and the recent history of science is largely a history of systems. The word is already there, waiting for someone to connect the pieces: 1543, the solar system; 1628, the circulatory system; 1900, the nervous system; 1902, the endocrine system; 1956, the earliest mention of computer systems. In 1962, a NASA technician became the first person to say, “All systems go,” which isn’t a bad description of modernity itself. Read more »

In the service of seeking truth, there would seem to be value in intellectual diversity, both in keeping ourselves honest and in the possibility of new ideas coming from unexpected quarters. That’s true in the natural sciences, but even more so in the humanities and social sciences, where the right/wrong distinction is sometimes less clear. But academia isn’t always diverse; as an empirical fact, there are a lot more liberals on university faculties than there are conservatives. I talk with Musa al-Gharbi about why this is true — self-selection? discrimination? — the extent to which it’s a real problem, and how we should better think about the value of diverse viewpoints.

In the service of seeking truth, there would seem to be value in intellectual diversity, both in keeping ourselves honest and in the possibility of new ideas coming from unexpected quarters. That’s true in the natural sciences, but even more so in the humanities and social sciences, where the right/wrong distinction is sometimes less clear. But academia isn’t always diverse; as an empirical fact, there are a lot more liberals on university faculties than there are conservatives. I talk with Musa al-Gharbi about why this is true — self-selection? discrimination? — the extent to which it’s a real problem, and how we should better think about the value of diverse viewpoints.

At 7:47 a.m. on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, Dr. Jay Butler pounded out a grim email to colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

At 7:47 a.m. on the Sunday of Memorial Day weekend, Dr. Jay Butler pounded out a grim email to colleagues at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Today I am in Saddar, the former colonial center, clamorous and poetically falling to bits. Pakistan is a particularly loud country (“Well, yes,” a famous doctor once countered, rolling his eyes, “there are people here,” yet I stand by it), and Saddar is no different. Once a pedestrian zone crisscrossed by tram lines, it is now clogged by technicolor buses and auto-rickshaws, dusty vans, beat-up cars, or the tinted 4 x 4 of a Very Important Person, complete with armed bodyguards limply hanging off the side like party streamers. Traffic cops, elegant in starched white uniforms, stand bravely amidst the chaos to direct it with waving arms and screeching whistles. Saddar is home to the Karachi Press Club, the Cotton Exchange, the City Railway Station and, of course, the experiment in human ingenuity that is the parking lot outside the National Bank. Cars are parked in tight rows, squeezed into whatever available space, no sensible way to vacate. A smattering of biryani restaurants lines the far end of the lot. Dilawar (a young Pushtun with green eyes, a migrant from the cold north) hollers for the other “valets” and, consolidating their manpower, lift stationary cars out of the way, hooting encouragement, so I can reverse.

Today I am in Saddar, the former colonial center, clamorous and poetically falling to bits. Pakistan is a particularly loud country (“Well, yes,” a famous doctor once countered, rolling his eyes, “there are people here,” yet I stand by it), and Saddar is no different. Once a pedestrian zone crisscrossed by tram lines, it is now clogged by technicolor buses and auto-rickshaws, dusty vans, beat-up cars, or the tinted 4 x 4 of a Very Important Person, complete with armed bodyguards limply hanging off the side like party streamers. Traffic cops, elegant in starched white uniforms, stand bravely amidst the chaos to direct it with waving arms and screeching whistles. Saddar is home to the Karachi Press Club, the Cotton Exchange, the City Railway Station and, of course, the experiment in human ingenuity that is the parking lot outside the National Bank. Cars are parked in tight rows, squeezed into whatever available space, no sensible way to vacate. A smattering of biryani restaurants lines the far end of the lot. Dilawar (a young Pushtun with green eyes, a migrant from the cold north) hollers for the other “valets” and, consolidating their manpower, lift stationary cars out of the way, hooting encouragement, so I can reverse. Austria between the world wars fostered an extraordinary number of talents in diverse fields: Sigmund Freud in psychology, Arnold Schoenberg in music, Karl Kraus in journalism, Robert Musil in literature, Gustav Klimt in art, the Bauhaus in architecture, and the “Austrian school” in economics. In some of these areas, the overriding ethos was hostility to what the Bauhaus called “ornament.” The Vienna Circle of philosophers, led by Moritz Schlick, hoped to cleanse philosophy of anything vague or, to use their favorite term of abuse, “metaphysical.” Some members also aspired to provide firm foundations for knowledge, an ambition that can be traced back to Descartes and the 17th-century rationalists.

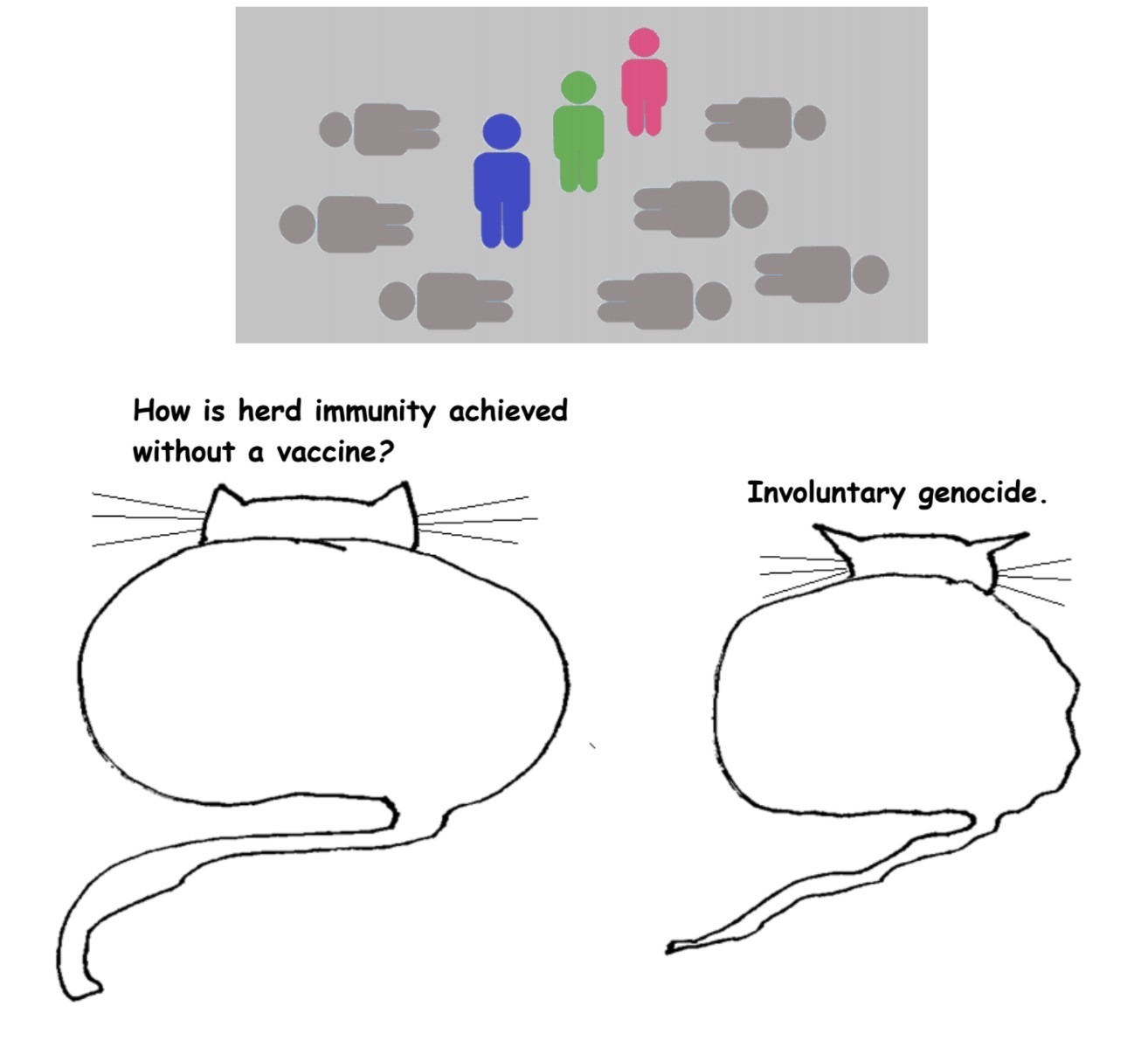

Austria between the world wars fostered an extraordinary number of talents in diverse fields: Sigmund Freud in psychology, Arnold Schoenberg in music, Karl Kraus in journalism, Robert Musil in literature, Gustav Klimt in art, the Bauhaus in architecture, and the “Austrian school” in economics. In some of these areas, the overriding ethos was hostility to what the Bauhaus called “ornament.” The Vienna Circle of philosophers, led by Moritz Schlick, hoped to cleanse philosophy of anything vague or, to use their favorite term of abuse, “metaphysical.” Some members also aspired to provide firm foundations for knowledge, an ambition that can be traced back to Descartes and the 17th-century rationalists. Cancer is a global health concern. There are over 100 types of cancer, which taken together, kill more than 10 million people across the world each year. Although localised cancers can be treated successfully through excision or localised radiotherapy, metastatic cancers spread throughout the body and are incurable, eventually leading to death. Once cancer cells have metastasised, they grow aggressively and are resistant to virtually all treatments. Despite enormous funds and dedicated efforts put into cancer research over the last half-century, half of all people diagnosed with cancer still die from their disease.

Cancer is a global health concern. There are over 100 types of cancer, which taken together, kill more than 10 million people across the world each year. Although localised cancers can be treated successfully through excision or localised radiotherapy, metastatic cancers spread throughout the body and are incurable, eventually leading to death. Once cancer cells have metastasised, they grow aggressively and are resistant to virtually all treatments. Despite enormous funds and dedicated efforts put into cancer research over the last half-century, half of all people diagnosed with cancer still die from their disease. On a chilly morning in February, about a thousand Chinese immigrants, Chinese Americans and others filled the streets of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. They marched down Grant Avenue led by a bright red banner emblazoned with the words “Fight the Virus, NOT the People,” followed by Chinese text encouraging global collaboration to fight Covid-19 and condemning discrimination. Other signs carried by the crowd read: “Time For Science, Not Rumors” and “Reject Fear and Racism.” They were responding to incidents of bias and

On a chilly morning in February, about a thousand Chinese immigrants, Chinese Americans and others filled the streets of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. They marched down Grant Avenue led by a bright red banner emblazoned with the words “Fight the Virus, NOT the People,” followed by Chinese text encouraging global collaboration to fight Covid-19 and condemning discrimination. Other signs carried by the crowd read: “Time For Science, Not Rumors” and “Reject Fear and Racism.” They were responding to incidents of bias and

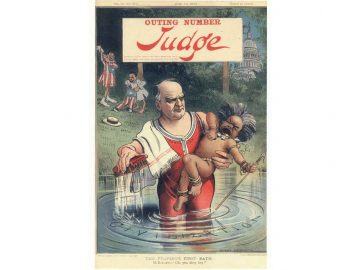

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S.  Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.

Last month’s most popular movie on Netflix is a horror show in the guise of a documentary. In 2020, reality has turned scarier than fiction, and The Social Dilemma expends more dread per minute than any episode of Black Mirror. It’s a timely, manipulative film, built for one purpose: to scare the f*ck out of everyday Americans.