This Is the City That I love

This is the city That I Love. Habichuelas bubbling on the stovetop. The kitchen door opens to our backyard. My father cuts out a piece of the campo and plants it here in Brooklyn. There are neighbors who knock on the door with a broom to let us know they’re selling pasteles. The train rumbles into a screech in the background, “This is Gates Avenue, the next stop is…”

Where are the gentrifiers now? Who watch us, ignore us, copy us, deny us, reject us, shame us, question us, kill us, laugh at us? Who fight for their claim to be New Yorkers because they waited for the train for like 30 minutes that one time. Saw a rat pull out a pizza slice that one time. Stepped into a bodega and bought a baconeggandcheese that one time.

Where are the gentrifiers now? The ones who suck this city dry. Chew at it and spit up its bones. They say they love this city. But they never loved us.

We have always made this city breathe. Pumped its heart with our bare hands. Pressed our lips against the concrete and brought air into its lungs. Held up its rib cage and spine even as our own skeletons were crushed by factory machines. Our lungs punctured by the chemicals in the dumps. Our blood rising against our arteries in protest of the food deserts, the stress, the generational trauma.

Here it is. Here is New York. Here is the poor, the working class, the immigrants, the undocumented, Black and brown, the descendants of a Jim Crow south and invaded continents. The dead.

Have you finally caught the pain of this city? Felt it lodge deep in your throat?

I call my mom and she tells me that the ambulance sirens are a constant. They run down Broadway towards Woodhull Hospital, raising her skin into goosebumps.

An essential worker. She goes on to tell me stories of her job in the senior home in the Bronx. How she’s learning to transition to online masses and prayers and English classes too. I hold her face through the screen. She smiles and laughs. I ask for her blessing, “’cion Mami.” She responds,

“I pray for you and you pray for me mija.”

by Rosemary Ferreira

from Split This Rock

Author’s reading: here

A common refrain in the social sciences is that evolutionary psychological hypotheses are “just-so stories.” Amazingly, no evidence is typically adduced for the claim—the assertion is usually just made tout court. The crux of the just-so charge is that evolutionary hypotheses are convenient narratives that researchers spin after the fact to accord with existing observations. Is this true?

A common refrain in the social sciences is that evolutionary psychological hypotheses are “just-so stories.” Amazingly, no evidence is typically adduced for the claim—the assertion is usually just made tout court. The crux of the just-so charge is that evolutionary hypotheses are convenient narratives that researchers spin after the fact to accord with existing observations. Is this true?

In 2020, much of the public discussion of social issues revolves around notions of identity. Ideas about race, reformulations of gender, and considerations of class or religious confession. But it is not often stated that these identity categories are qualitatively different, and these differences have different implications for the real world. Some reflection on the real-world consequences of identity ought to make this apparent. Why is a party based on working-class solidarity far less sinister than a party based on a racial or ethnic group? Perhaps because being working-class is not a fixed identity, and solidarity is open to all. One’s race or ethnicity is viewed as more static. Most of us can imagine struggling to pay bills and keep a roof over our heads, but few can imagine being another race. Race-thinking is anti-empathetic by its nature.

In 2020, much of the public discussion of social issues revolves around notions of identity. Ideas about race, reformulations of gender, and considerations of class or religious confession. But it is not often stated that these identity categories are qualitatively different, and these differences have different implications for the real world. Some reflection on the real-world consequences of identity ought to make this apparent. Why is a party based on working-class solidarity far less sinister than a party based on a racial or ethnic group? Perhaps because being working-class is not a fixed identity, and solidarity is open to all. One’s race or ethnicity is viewed as more static. Most of us can imagine struggling to pay bills and keep a roof over our heads, but few can imagine being another race. Race-thinking is anti-empathetic by its nature. Despite her precocity and her early determination, it took Somerville half a lifetime to come abloom as a scientist — the spring and summer of her life passed with her genius laying restive beneath the frost of the era’s receptivity to the female mind. When Somerville was forty-six, she published her first scientific paper — a study of the magnetic properties of violet rays — which earned her praise from the inventor of the kaleidoscope, Sir David Brewster, as “the most extraordinary woman in Europe — a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman.” Lord Brougham, the influential founder of the newly established Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge — with which Thoreau would take issue thirty-some years later by making a case for

Despite her precocity and her early determination, it took Somerville half a lifetime to come abloom as a scientist — the spring and summer of her life passed with her genius laying restive beneath the frost of the era’s receptivity to the female mind. When Somerville was forty-six, she published her first scientific paper — a study of the magnetic properties of violet rays — which earned her praise from the inventor of the kaleidoscope, Sir David Brewster, as “the most extraordinary woman in Europe — a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman.” Lord Brougham, the influential founder of the newly established Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge — with which Thoreau would take issue thirty-some years later by making a case for  A direct line runs between the vibrant, colorful, and earthy diction of canting to cockney rhyming slang, or the endangered dialect of Polari used for decades by gay men in Great Britain, who lived under the constant threat of state punishment. All of these tongues are “obscene,” but that’s a function of their oppositional status to received language. Nothing is “dirty” about them; they are, rather, rebellions against “proper” speech, “dignified” language, “correct” talking, and they challenge that codified violence implied by the mere existence of the King’s Speech. Their differing purposes, and respective class connotations and authenticity, are illustrated by a joke wherein a hobo asks a nattily dressed businessman for some change. “’Neither a borrower nor a lender be’—that’s William Shakespeare,” says the businessman. “’Fuck you’—that’s David Mamet,” responds the panhandler. A bit of a disservice to the Bard, however, who along with Dekker and Middleton could cant with the best of them. For example, within the folio one will find “bawling, blasphemous, incharitible dog,” “paper fac’d villain,” and “embossed carbuncle,” among such other similarly colorful examples.

A direct line runs between the vibrant, colorful, and earthy diction of canting to cockney rhyming slang, or the endangered dialect of Polari used for decades by gay men in Great Britain, who lived under the constant threat of state punishment. All of these tongues are “obscene,” but that’s a function of their oppositional status to received language. Nothing is “dirty” about them; they are, rather, rebellions against “proper” speech, “dignified” language, “correct” talking, and they challenge that codified violence implied by the mere existence of the King’s Speech. Their differing purposes, and respective class connotations and authenticity, are illustrated by a joke wherein a hobo asks a nattily dressed businessman for some change. “’Neither a borrower nor a lender be’—that’s William Shakespeare,” says the businessman. “’Fuck you’—that’s David Mamet,” responds the panhandler. A bit of a disservice to the Bard, however, who along with Dekker and Middleton could cant with the best of them. For example, within the folio one will find “bawling, blasphemous, incharitible dog,” “paper fac’d villain,” and “embossed carbuncle,” among such other similarly colorful examples. There’s really nothing in

There’s really nothing in  The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a

The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a  You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in

You will recall that while I carried on and on about myself in  The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist

The blob is a cloud of turbulence in a large water tank in the lab of the University of Chicago physicist  The global pandemic has re-written the rules of global macroeconomic policy for us. We have witnessed significant monetary and fiscal policy innovation; growing unwillingness to accept that the design of stimulus should be independent of broader environmental and social goals; and a far more acute focus on the competence and scope of the State.

The global pandemic has re-written the rules of global macroeconomic policy for us. We have witnessed significant monetary and fiscal policy innovation; growing unwillingness to accept that the design of stimulus should be independent of broader environmental and social goals; and a far more acute focus on the competence and scope of the State. Will we be surprised again this November the way Americans were on Nov. 9, 2016 when they awoke to learn that reality TV star Donald Trump had been elected president? That outcome defied prognosticators and polls, and even Trump’s own expectation. “Oh, this is gonna be embarrassing,”

Will we be surprised again this November the way Americans were on Nov. 9, 2016 when they awoke to learn that reality TV star Donald Trump had been elected president? That outcome defied prognosticators and polls, and even Trump’s own expectation. “Oh, this is gonna be embarrassing,”  Arundhati Roy’s literary career has been one of a kind. Thrust into the limelight of the global publishing industry back in 1997 when her debut novel,

Arundhati Roy’s literary career has been one of a kind. Thrust into the limelight of the global publishing industry back in 1997 when her debut novel,  Urban Legends is a parabolic dish microphone pointed at history, collecting the waves that outsiders have bounced off the South Bronx. L’Official gathers representations of the South Bronx found in fiction, like Don DeLillo’s description of urban tourism in Underworld, and the ways it has been filtered through journalistic language. He proposes that classifications like “inner city” and the “ghetto” are also “versions of urban legends as well.” L’Official presents these ideas as euphemisms and “coded spatial signifiers for race,” which they are. In fact, the focus of Urban Legends is squarely on the views of those who never lived in the neighborhood. Very little of it touches on how the residents of the South Bronx represented themselves, and L’Official acknowledges this several times, best of all in the conclusion: “Though Urban Legends falls short of discussing ‘all kinds’ of artists, its aims were, and are, aligned with those of the Fort Apache Band, as articulated by Andy González: showing that art can, and does, emerge from an imperiled environment.” L’Official seems to know that hip-hop and graffiti don’t need his help at this point. He writes that graffiti artists in the South Bronx—“most of whom pointedly referred to themselves as writers—would no doubt tell you, graffiti was Bronx literature, and a populist form at that, which hardly required an agent or a publishing contract to reach an audience.”

Urban Legends is a parabolic dish microphone pointed at history, collecting the waves that outsiders have bounced off the South Bronx. L’Official gathers representations of the South Bronx found in fiction, like Don DeLillo’s description of urban tourism in Underworld, and the ways it has been filtered through journalistic language. He proposes that classifications like “inner city” and the “ghetto” are also “versions of urban legends as well.” L’Official presents these ideas as euphemisms and “coded spatial signifiers for race,” which they are. In fact, the focus of Urban Legends is squarely on the views of those who never lived in the neighborhood. Very little of it touches on how the residents of the South Bronx represented themselves, and L’Official acknowledges this several times, best of all in the conclusion: “Though Urban Legends falls short of discussing ‘all kinds’ of artists, its aims were, and are, aligned with those of the Fort Apache Band, as articulated by Andy González: showing that art can, and does, emerge from an imperiled environment.” L’Official seems to know that hip-hop and graffiti don’t need his help at this point. He writes that graffiti artists in the South Bronx—“most of whom pointedly referred to themselves as writers—would no doubt tell you, graffiti was Bronx literature, and a populist form at that, which hardly required an agent or a publishing contract to reach an audience.” IN HER 2007 BOOK, Awkward: A Detour, Mary Cappello posits the title state as a natural response to a world indifferent to our comfort or desires. “Awkwardness could be an effect of the rough handling of reality over which one has no control,” she proposes, and over the course of her wide-ranging, digressive, book-length essay, Cappello approaches the question of awkwardness from a variety of different angles. Melding memoir, literary and film criticism, etymological study, and many other modes, her book offers up a range of perspectives on and definitions of the state of awkwardness, all of which speak to the gap between our natural inclinations and the ways we are forced to adjust these inclinations to fit both a physical world and a social environment that routinely refutes them. “Each day on earth,” Cappello writes, “is at base an endless adjustment to there being too much or not enough, to there being something missing or something extra,” and it’s in this adjustment that awkwardness occurs.

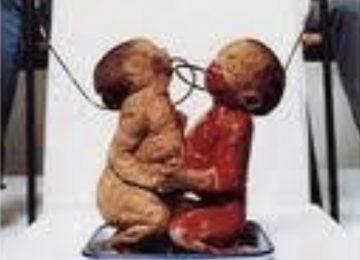

IN HER 2007 BOOK, Awkward: A Detour, Mary Cappello posits the title state as a natural response to a world indifferent to our comfort or desires. “Awkwardness could be an effect of the rough handling of reality over which one has no control,” she proposes, and over the course of her wide-ranging, digressive, book-length essay, Cappello approaches the question of awkwardness from a variety of different angles. Melding memoir, literary and film criticism, etymological study, and many other modes, her book offers up a range of perspectives on and definitions of the state of awkwardness, all of which speak to the gap between our natural inclinations and the ways we are forced to adjust these inclinations to fit both a physical world and a social environment that routinely refutes them. “Each day on earth,” Cappello writes, “is at base an endless adjustment to there being too much or not enough, to there being something missing or something extra,” and it’s in this adjustment that awkwardness occurs. There are two dead babies sitting in a medical pan inside a nondescript room. These babies face one another. Are they conjoined twins? There are tubes connected to the twin cadavers. A Chinese couple, a man and a woman, sit in chairs on either side of the babies. The tubes from the babies are connected to the arms of the couple. They are feeding their own blood into the mouths of the dead babies, who receive the elixir without discernible effect as the blood dribbles down their faces. It is a horrendous scene, made all the more horrendous by the fact that it is so compelling to look at, so fascinating to think about. Are these people trying to help the babies, connect with them somehow? Are they making fun of these dead babies or of the situation? Are we meant to laugh, cry, recoil in horror? What is this disturbing scene and why are we being subjected to it?

There are two dead babies sitting in a medical pan inside a nondescript room. These babies face one another. Are they conjoined twins? There are tubes connected to the twin cadavers. A Chinese couple, a man and a woman, sit in chairs on either side of the babies. The tubes from the babies are connected to the arms of the couple. They are feeding their own blood into the mouths of the dead babies, who receive the elixir without discernible effect as the blood dribbles down their faces. It is a horrendous scene, made all the more horrendous by the fact that it is so compelling to look at, so fascinating to think about. Are these people trying to help the babies, connect with them somehow? Are they making fun of these dead babies or of the situation? Are we meant to laugh, cry, recoil in horror? What is this disturbing scene and why are we being subjected to it?